At 10:13 PM last night, I sent Atlantic assistant editor Joe Pinsker an email to say I was writing an article about all the after-work time we spend on email.

Before the clock struck 10:14, Joe had replied: “Sounds good.”

Without having any idea that I would share his correspondence, Joe anticipated that I needed an anecdotal lede, and he kindly provided it. For a certain class of workers, late evening isn’t time off work. It’s time on email, time to show your addressees the true meaning of workaholic, and time to return to a job from which you can never truly sign out.

The specter of endless email doesn’t haunt all workers equally. The most common jobs in America, like cashiers, retail salespeople, and food and service workers, don’t need to be email-intensive. They often work within a stable flow of customers and do routine-heavy work for clients whose needs don’t change dramatically from day to day.

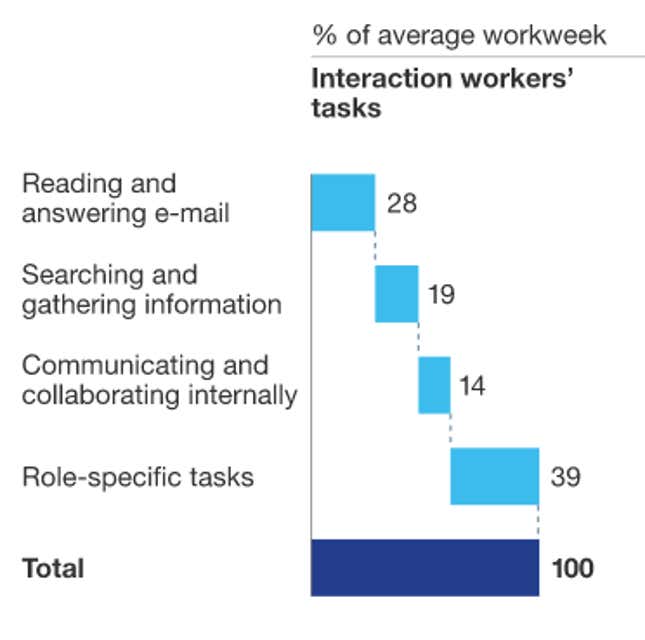

But in other white-collar industries—law, consulting, advertising, fashion, media, non-profits, fundraising, politics—individual workers are constantly working with new clients and partners, whose needs require constantcontacting, pinging, base-touching, out-reaching, and so on. Email isn’t just for your cross-country clients; it’s just as likely to be for your cross-desk colleagues. The upshot is a ceaseless flow of correspondences that often bleeds over into dusk. Email consumes an average of 13 hours per week, according to a McKinsey Global Institute paper, or 28% of the average workweek. With the typical “knowledge” worker—that is: somebody whose professional output is creative—earning $75,000 a year, that means “the time spent on reading and answering email costs a company $20,990 per worker per year.” (No wonder there are all these people trying to reform it.)

Put another way, for every ten minutes we spend on “role-specific tasks” outside of our inbox, we spend roughly seven minutes on email.

Is this a good thing, a bad thing, or just a … thing? Brad Stone, a reporter who shares my affection for late-night emailing, calls the nocturnal allure of our inbox “the new night shift.” In Bloomberg Businessweek, he writes:

The irony of the new night shift is that white-collar professionals have never had more flexibility and autonomy. Companies regularly bend over backward to appear family-friendly and allow working moms and dads to leave the office early to get the kids. The young and childless, meanwhile, continue working, creating a guilt that forces parents to log back on after dinner.

“It really is a global economy,” says David Mars, a New York venture capitalist. But if the pressures of globalization and a flimsy economy have endangered the set-hour workweek, mobile technology has obliterated it. In an unpublished Harvard Business School survey that I reviewed last year, American managers and workers reported that they were “on”—either working or “monitoring” work while being accessible—almost 90 hours a week. With this new denominator, email isn’t 28% of a 45-hour workweek. It’s 14% of a workweek that begins when our heads lift off the pillow and ends when we fall, face-first and exhausted, back into it. Wake-up-to-power-down is the new 9-to-5.

Separate from the pressures of a global economy, the impulse to log on at night seems, to me, purely domestic. I’m the one telling myself that the work is going to be there in the morning, so why not start whittling it down tonight? There’s also the social signal sent by a late-night email. After a certain hour, I’m not just sending a message; I’m also sending a message. Responding to somebody 24 hours late suggests a lack of diligence. Responding to that person around midnight takes the same amount of procrastination, but disguises it as industriousness: “Oh, hey, see that 1:04 AM timestamp? I guess I’m just that busy! (yet dedicated!).”

The culprit for my late-night email addiction isn’t the addresses in the “To:” and “From:” fields. It’s the name in my signature. We are doing this to ourselves.

This post originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site:

Why it’s so hard for whites to understand Ferguson