Poor devil: He used to terrify people. Now he’s reduced to hawking razor blades and ham.

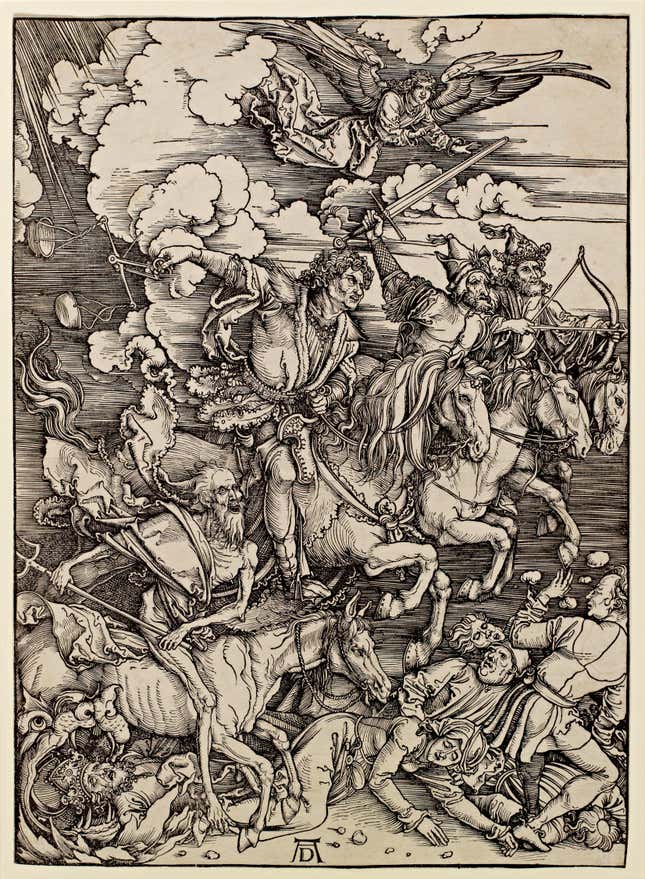

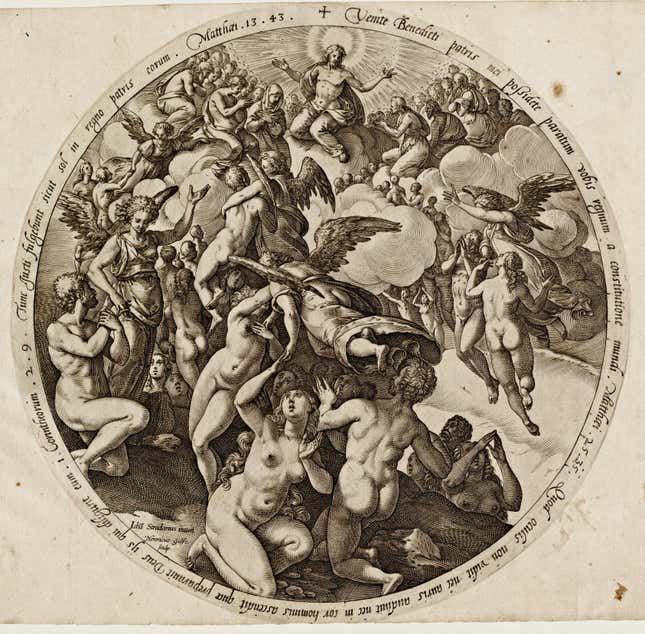

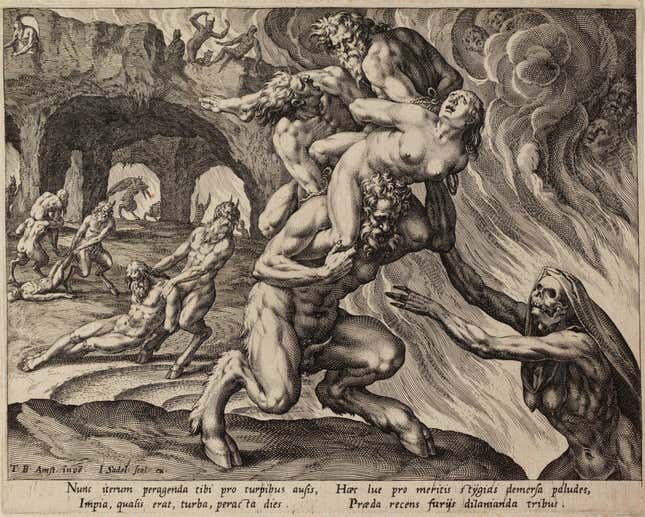

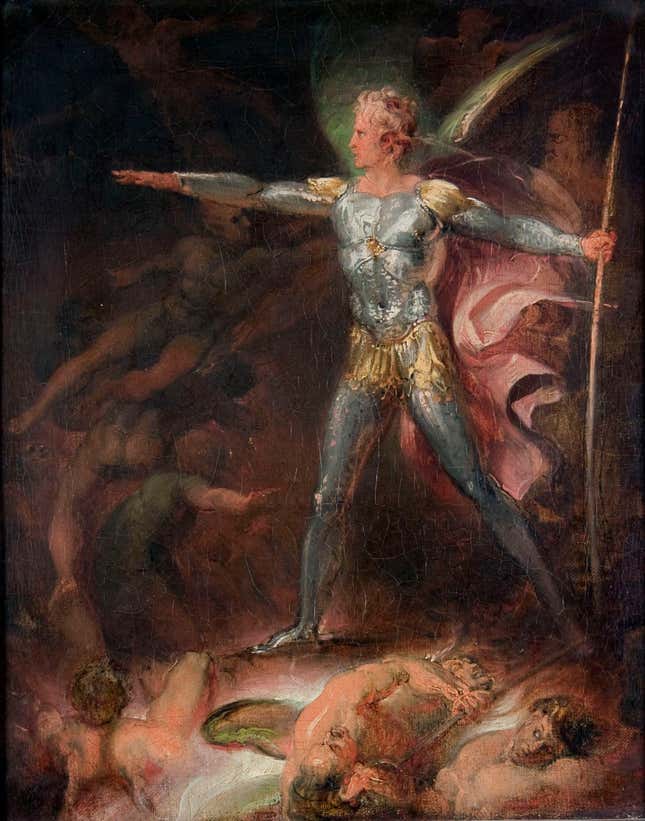

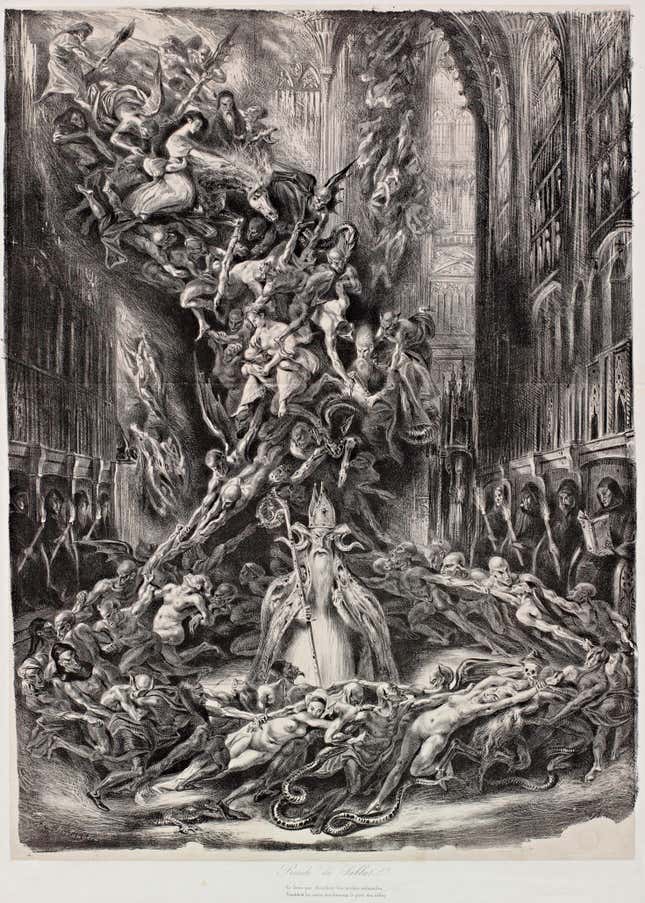

A new exhibition at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, “Sympathy for the Devil: Satan, Sin, and the Underworld,” traces Lucifer’s visual history, from his emergence in the Middle Ages as a horned, cloven-hoofed, foul-smelling, diabolical creature of the night to his denuded and largely ironic image today.

“By around 1500, his visage and characteristics were pretty well set,” Bernard Barryte, Cantor’s curator of European art, tells Quartz. “He was initially a conflation of sundry things. Everything from Pan to Near Eastern gods got mushed together in the Middle Ages and became what we know of as the devil.”

In the 16th and 17th century, grisly paintings of the Evil One were intended literally, Barryte says.”They were meant to have a moral effect, which is why artists made him awful looking. Even if you were educated, you would wonder, ‘What if?’ No matter how skeptical one might be today, there was real faith underlying this imagery.”

The Enlightenment began to change that. As our conception of evil shifted, so did our personification of the devil. “He becomes more human, even romanticized, after the popular revolutions of the late 18th century, especially the French Revolution,” Barryte says. In the 19th century, the devil was often depicted as a “shrewd and wily dandy,” a Mephistophelean figure who would trick you out of your soul, not brutally tear it from you. “Fear is no longer his most effective tactic,” Barryte says. “And in the 20th century, he all but disappears except in advertisements.”

In his place—well, look in the mirror. “Hell is other people, is how Jean-Paul Sartre put it,” Barryte says. “All the sources of evil seemed to shift from some horrific other to mankind itself.”

For a nostalgic look at the devil’s many guises (along with depictions of his realm and minions), here’s a selection of works in the exhibition, which is on view through November 30: