The postelection news cycle is still dwelling on the mystery: How did Barack Obama become the first president since the Great Depression to win a second term with unemployment as high as 8%? Even before the vote, the economic metrics that prognosticators such as Yale’s Ray Fair use to forecast election results pointed to a defeat for Obama, given persistently weak growth in per capita income over his first four years. The polls showing that most voters saw the economy as the key issue only added to the mystery of how Obama beat the odds. The answer may be that, in their gut, voters understand that the United States is not recovering from a normal recession, but from the worst crisis since the Depression, and therefore they chose to give Obama four more years, just as they did for Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1936.

The American economy has in fact not performed badly in terms of GDP growth over the last four years, not when compared to its own previous track record in severe crises, or to other countries. The forecaster who expected an Obama defeat focused on how the debt problem is undermining US growth, which has fallen from a long-term rate of 3.4% in the decades before 2007 to just 2% this year, and is running slower than during the recovery phase of most postwar recessions. U.S. economic output is now 10% below its trend line before the crisis and still falling, which is the real reason for high unemployment. This case for the historically “weak recovery” was the essence of the case against Obama’s handling of the economy.

Voters seemed to choose, intuitively if not deliberately, the historical and global perspective of Harvard economists Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, who argue that the relevant point of comparison is not the dozen or so recessions the United States has seen since World War II, but the very different case of systemic financial crises (pdf). These are more traumatic and rare, and by this standard, the United States is recovering lost per capita output faster than it did following previous systemic crises, from the meltdown of 1873 through the Depression, and also faster than most of the Eurozone nations following the systemic crisis of 2008.

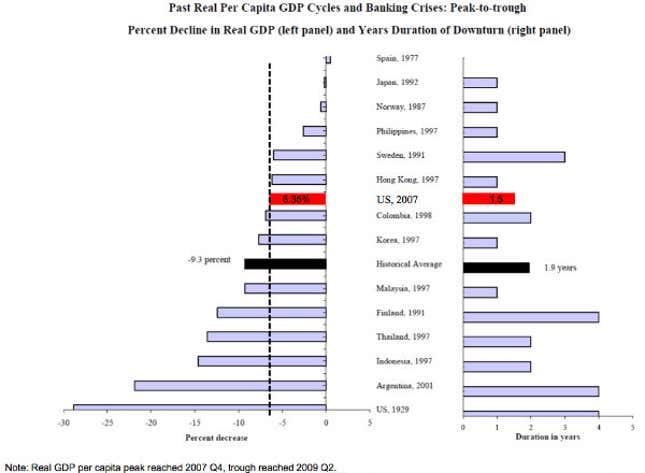

Many studies show that people feel most content when they are prospering relative to their neighbors, and America is doing relatively well even compared to emerging nations in earlier debt crises. A recent update on Rogoff and Reinhart’s work shows that, compared to 20 major international banking crises from Norway in 1899 through Thailand in 1997, the recent drop in US home prices, stock market values, employment, and real GDP are all below the historic average. (See Figure 1 below from the updated report) It also shows that the spike in US public debt was below the historic norm through the end of 2011, but this is the point where voter patience may turn faster than Obama would like.

The history of financial crises suggests that the debt burden has to be addressed now. In the developed world, the two most successful cases of recovery from a debt crisis were Sweden and Finland in the 1990s, and both began by cutting debt in households and corporations, while continuing to raise public debt to stimulate the economy. That is the path the United States has followed—and followed more successfully than other rich countries since 2008–with steep declines in U.S. corporate and household debt. But this is the critical juncture. The Scandinavian cases show that, four years into the crisis or about where the United States is today, the government needs to shift aggressively from stimulating the economy to putting in place a long-term plan to lower the public debt.

It can’t be just any plan. In certain quarters there is a steady refrain about how the only way to balance the budget is to cut spending and raise taxes. But research clearly shows that the recovery is likely to be much stronger if the debt is reduced through spending cuts rather than tax increases, because business investment responds positively to the former, negatively to the latter.

Over the last quarter century, eight European countries have undergone periods of sharp government debt reduction, and those that reduced debt mainly or only through spending cuts, including Britain and Austria, saw their economies speed up during the belt-tightening process, and after some initial pain. In the Netherlands as well as Sweden and Finland, which saw particularly large gains in the average annual real GDP growth rate, the governments actually lowered taxes while cutting spending. In contrast, the countries of southern Europe (Italy, Greece, France) tried to put the budget in balance mainly through tax increases, and all saw GDP growth slow down.

The US economy looks likely to take some pain in the coming year. The market’s worst fear is the “fiscal cliff” that looms in January, when current law would impose a combination of tax increases and spending cuts equal to 5 percent of GDP, which is almost sure to induce a recession if Congress doesn’t act. However, any risk that is this clearly telegraphed typically get resolved, even in Congress. The more likely risk is that Washington begins the process of debt reduction with a compromise package that could reduce growth by nearly 2% of GDP. That’s a step in the right direction, long term, but could make for a rough 2013.

Over the coming decade, the global economic race will be decided in good part by which nations are first to tackle the debt problem, and one often overlooked factor is that the wealthy can cope with large debts more easily than the poor. By that measure, the total US debt burden of 350% of GDP may pose less of a challenge to Washington than China’s total debt burden of 180% of GDP poses to Beijing. The bigger picture for 2013 is that if Washington can produce a credible road map to lowering public debt, it could keep the United States on track to be a Breakout Nation—as the strongest growth story in the developed world—this decade.