This is Microsoft’s surprising ‘Plan B’ for mobile

Microsoft’s mobile comeback—at least how the company had intended—isn’t happening.

Microsoft’s mobile comeback—at least how the company had intended—isn’t happening.

Despite Microsoft’s early presence in the smartphone industry—years ahead of Apple and Google—and recent critical acclaim for the software, Windows Phone is a flop. In the second quarter, Microsoft’s global smartphone market share was just 2.5%, according to IDC. That represented a decline from the previous year in both share and actual shipments, despite a growing smartphone market. It truly is a two-horse race, with Google and Apple representing a combined 96.4% of shipments last quarter.

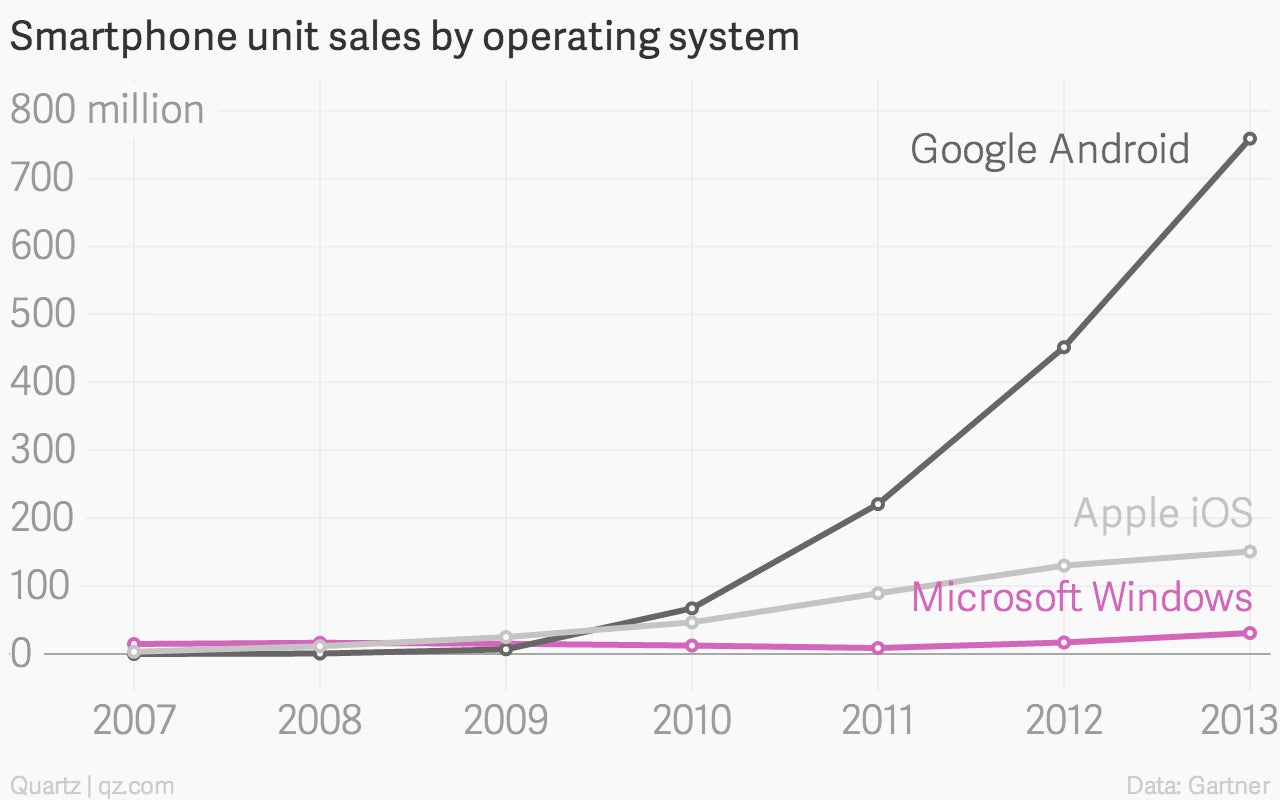

A zoomed-out view of the smartphone industry shows just how completely Microsoft has missed the smartphone revolution.

But Microsoft, under new CEO Satya Nadella, still aspires to be a major player in the mobile industry. And this is where its stunted market share of smartphone software platforms really hurts. Not only is it missing out on potential hardware revenue, but it’s also losing a distribution channel for its own software and services. Google and Apple have used their popularity to push other software and services—many pre-installed on phones, or easily added on—like maps, media and app stores, cloud storage for backups and photos, and voice-activated search. The list of the 25 most popular smartphone apps in the US includes several from Google and Apple, but just one controlled by Microsoft: Skype.

But Microsoft has a new strategy that sounds like nothing it would have muttered just a few years ago: “We’re going to be everywhere,” a Microsoft exec told me in a recent meeting.

If you look now, it’s already starting to happen. Microsoft—yes, Microsoft—is building and shipping apps for iOS, Android, and the web. And people aren’t ignoring them. Its Office apps for iPad have been downloaded more than 35 million times, and Word is routinely a top-10 iPad app. Its Word, Outlook, and OneDrive apps show up in the “Popular” section of Google’s Chrome app store. It’s working on more.

Why is Microsoft doing this? Part of it is that the company now realizes—and readily admits—that it’s behind. In today’s tech world, its true market share isn’t represented by its 90%+ dominance of the PC market, but a more modest 14% share of total global smartphone, PC, and tablet sales. Microsoft is now the underdog, and to survive this era, it will have to build software for the platforms people are using—namely, iOS and Android.

Meanwhile, Microsoft is also in the early stages of trying to convert its global user base to cloud-based subscription services, such as Office 365, which starts at $7 per month for home users. The hope is to eventually trade its outdated—but highly profitable—business of licensing software via one-time fees for recurring subscription revenue. Early progress is promising: Microsoft boasted 5.6 million Office 365 “Home and Personal” customers at the end of June, up more than one million from the previous quarter. And in its commercial business, it said that both Office 365 and its Azure cloud-computing business more than doubled year-over-year.

But two big questions remain: First, will Microsoft ever generate the sort of sales and profits from its cloud services that it did at the height of its Windows and Office dominance? Or is this new Microsoft inherently a smaller business? And second, as a new generation of home and business users rises, will it stick with Microsoft products? Or will they choose others from rivals like Google, Apple, and Dropbox? Microsoft’s Office and Windows advantage was that it was pretty much the only serious game in town. It still has some cachet, but the openness of the web—and Microsoft’s weak platform position in mobile—are hurting.