Oil plunged today below $100 a barrel, a psychological threshold that, if it holds, threatens the rulers of Russia and numerous OPEC states that rely on higher prices to mollify their populations. A critical question, then, is whether we are looking at a sustained period of lower prices or a blip before a swing back up.

The price of Brent crude—the type that dominates international trade—fell as low as $99.36 today, its lowest price in 14 months. (West Texas Intermediate, the oil produced in the United States, plummeted to $91.70 a barrel, frighteningly close to its own $90 threshold.)

Voices from OPEC said they are not alarmed and that prices will go back up over the next few months when Winter demand commences. Bernstein’s Oswald Clint told Quartz that the long-term trend is for prices to rise, supported by higher costs to produce oil and constrained supply.

But there is reason for OPEC members to worry. For starters, China’s GDP growth is slowing, Citi said in a Sept. 3 note to clients. Changes in GDP closely track oil demand, so that means that oil demand—the main factor underlying bullish long-term forecasts—is slowing, too.

This year, the Chinese are targeting GDP growth of 7.5%, lower than last year’s rate, and some analysts think it will struggle even to achieve that. Citi’s Ed Morse tells Quartz that growth will go lower still in the medium term–below 6%. “Anyone who thinks a rebound in Chinese oil demand will drive a rally in oil prices needs to think twice given [that] crude import growth is slowing and refined product net imports are in outright decline,” Citi wrote in the note.

Production constraints may also fail to raise oil prices. On his Financial Times blog, former BP executive Nick Butler writes that prices are falling despite contrary pressures, including unusual geopolitical upheaval (Ukraine, Iraq, Syria, and Libya) and oil sanctions on Iran and Russia. As an example, Libyan production is soaring after months of being off line—it is pumping 720,000 barrels a day, compared with 500,000 just a couple of weeks ago.

As a result, oil executives in search of higher prices will need to cut costs, Butler writes: “Goodbye once again to the corporate jets, the lavish expenses and the padded leather of town center offices.”

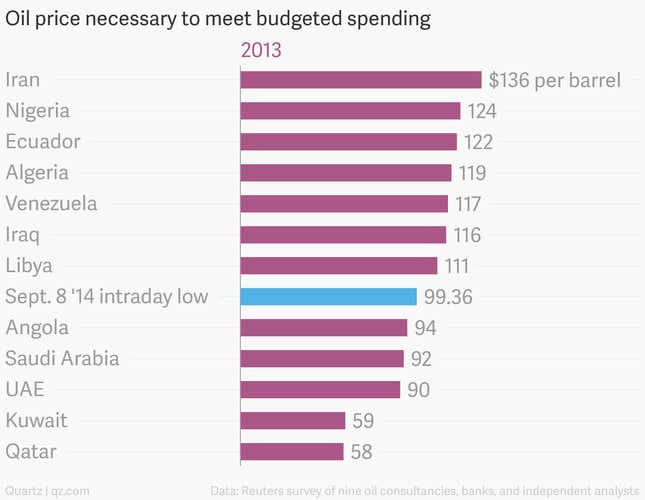

Which brings us back to the petro-rulers. Generally speaking, the oil-exporting nations are not democracies, but instead led by strongmen or royal families. To stay in power and keep their fiefdoms stable, they dole out perks such as subsidized energy prices, patronage jobs, special payments, and so on, and those perks can be expressed in a simple mathematical equation: the maximum number of barrels of oil they can drill per day multiplied by the price of oil. From that, you can derive the rough average oil price each nation requires to cover such spending.

Russian president Vladimir Putin, for instance, needs an oil price of roughly $110 to $117 a barrel to cover state expenses. With some fiscal finagling, he can weather bad days like these, as long as they don’t last for long.

As you see in the chart above, the same goes for a slew of OPEC nations. At least seven of them—and especially Iran—are in genuine trouble if Citi is right and Bernstein wrong.