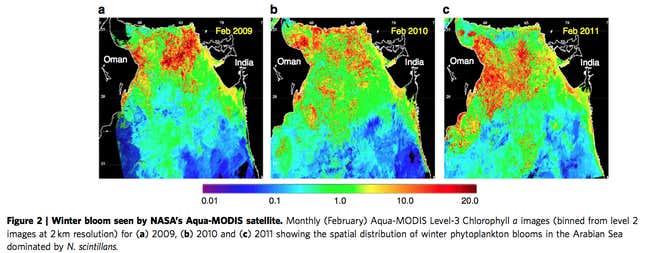

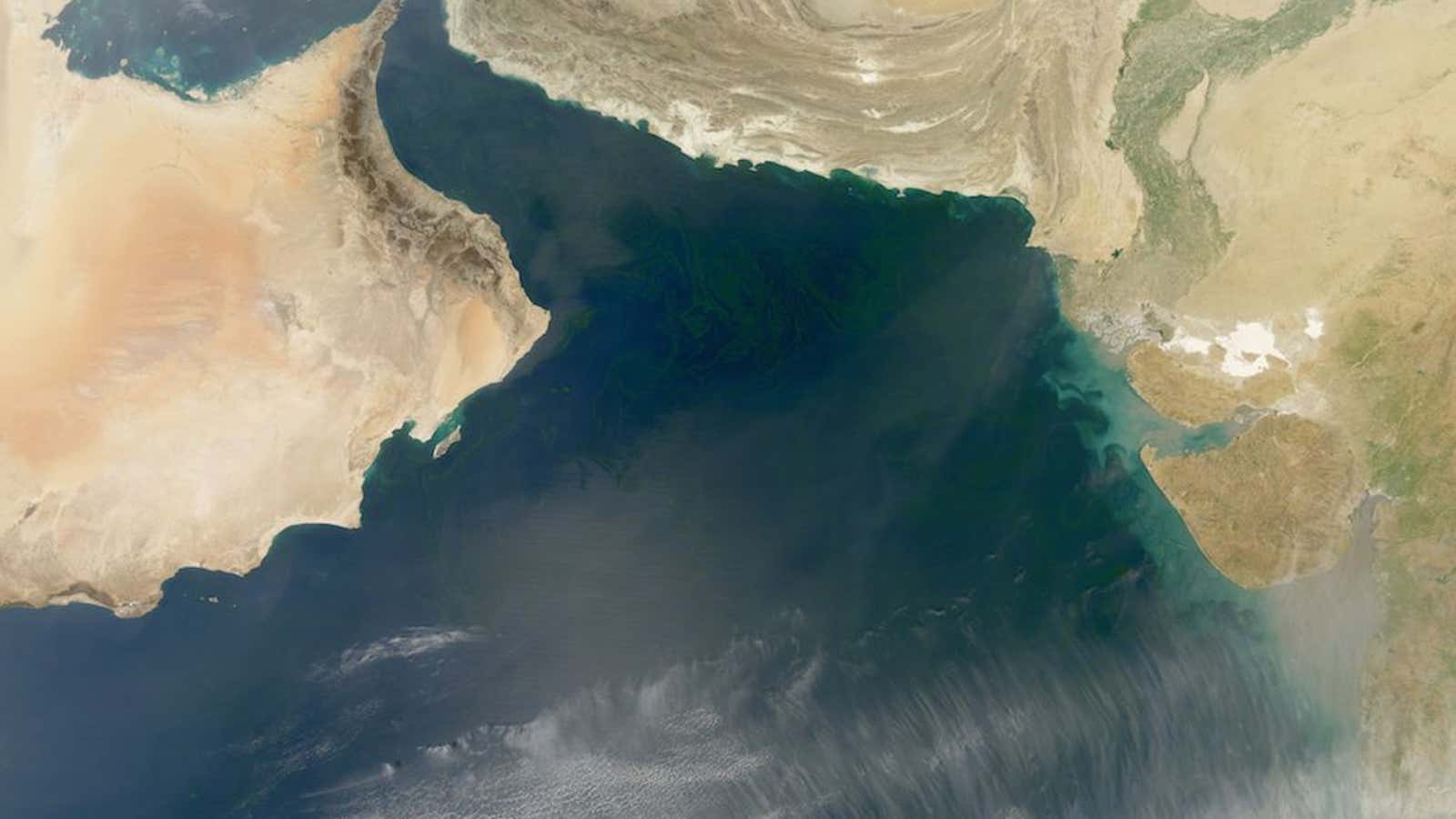

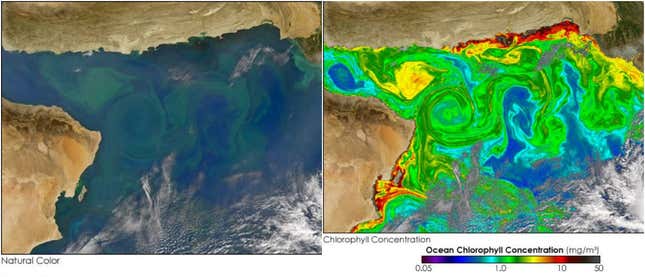

Every winter, millions of microscopic plankton cloud the waters that stretch from Oman to India. Though they only began appearing in the early 2000s, these algae now carpet a Texas-sized swath of the Arabian Sea, forming emerald swirls so dense you can see them from space.

Even though they are beautiful, the plankton have a lethal effect on plants and animals in the depths below.

Thanks to sewage pumped from the booming cities that flank the Arabian Sea, the plankton have flourished, altering the Arabian Sea’s food chain so thoroughly that it could endanger some 120 million people who depend on these waters for food, according to a new study.

The plankton invading the Arabian Sea are part velociraptor, part slum-lord. They feed on other plankton, flicking them into their mouths with tail-like flagella. Noctiluca scintillans, as the species is known, also hosts millions of green algae that live within its transparent cell walls. Like many land-plants, the chlorophyll that synthesizes sunlight is what gives these algae their green hue, absorbing carbon in the process. In a process that can be likened to paying rent, the green algae pass that energy onto their N. scintillans host.

This varied diet means the plankton are less reliant on a single food source than most species, a competitive advantage that helps them take over an ecosystem. In the Arabian Sea, this process began in the early 2000s, when scientists started noticing that N. scintillans blooms—as population explosions are known—coincided with the vanishing of diatoms, the native algae.

The diatoms’ disappearance is bad news. Diatoms are the base of the Arabian Sea’s food chain; even the biggest sharks rely on them to feed what ultimately becomes their prey. N. scintillans, on the other hand, are too big to substitute for the diatoms eaten by microscopic crustaceans. As a result, those crustaceans go without food, and their decline could in turn compromise the diet of other regional fish populations.

Another problem stemming from the rise of N. scintillans: the few creatures that will eat N. scintillans include jellyfish, which eat fish eggs and larvae. Since few fish feed on jellyfish, there’s nothing to keep their populations in check. As these gelatinous blobs sink to the bottom, they drag carbon with them, stripping oxygen from the water. Few animals can survive “dead zones” of oxygen-poor water. As the scientists discovered, N. scintillans thrives in these conditions; diatoms don’t. And once a dead zone sets in, it’s hard for the ocean to recover.

This might explain why, for example, Oman’s fishermen caught nearly a fifth fewer fish last year, or why fishermen in Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have seen their catches shrink.

So what’s the root of the problem? The scientists point to the boom in population, which has led to increasing use of fertilizers and huge torrents of organic waste being thrown into the water. That waste feeds the algae that support N. scintillans. While Mumbai’s population has doubled to 21 million in a decade, more than two-thirds of Karachi’s wastewater is flushed into the Arabian Sea untreated.