By watching his children play, Edward Adelson got the idea for a new kind of robot. “I expected to be fascinated by watching how they used their visual systems, but I was actually more fascinated by how they used their fingers,” the MIT professor of vision science said. ”But since I’m a vision guy, the most sensible thing, if you wanted to look at the signals coming into the finger, was to figure out a way to transform the mechanical, tactile signal into a visual signal.”

So Adelson developed the GelSight sensor, which is basically metallic paint on transparent rubber. When the sensor is pressed against an object, the rubber molds to it and the paint reflects the light in a way that allows the robot to make more precise measurements of the world around it. A modified version of the sensor has now been used to make robots that MIT and Northeastern University say has “unprecedented” abilities to manipulate objects.

“People have been trying to do this for a long time,” said Robert Platt, the robotics expert at Northeastern who is part of Adelson’s research team. “They haven’t succeeded because the sensors they’re using aren’t accurate enough and don’t have enough information to localize the pose of the object that they’re holding.”

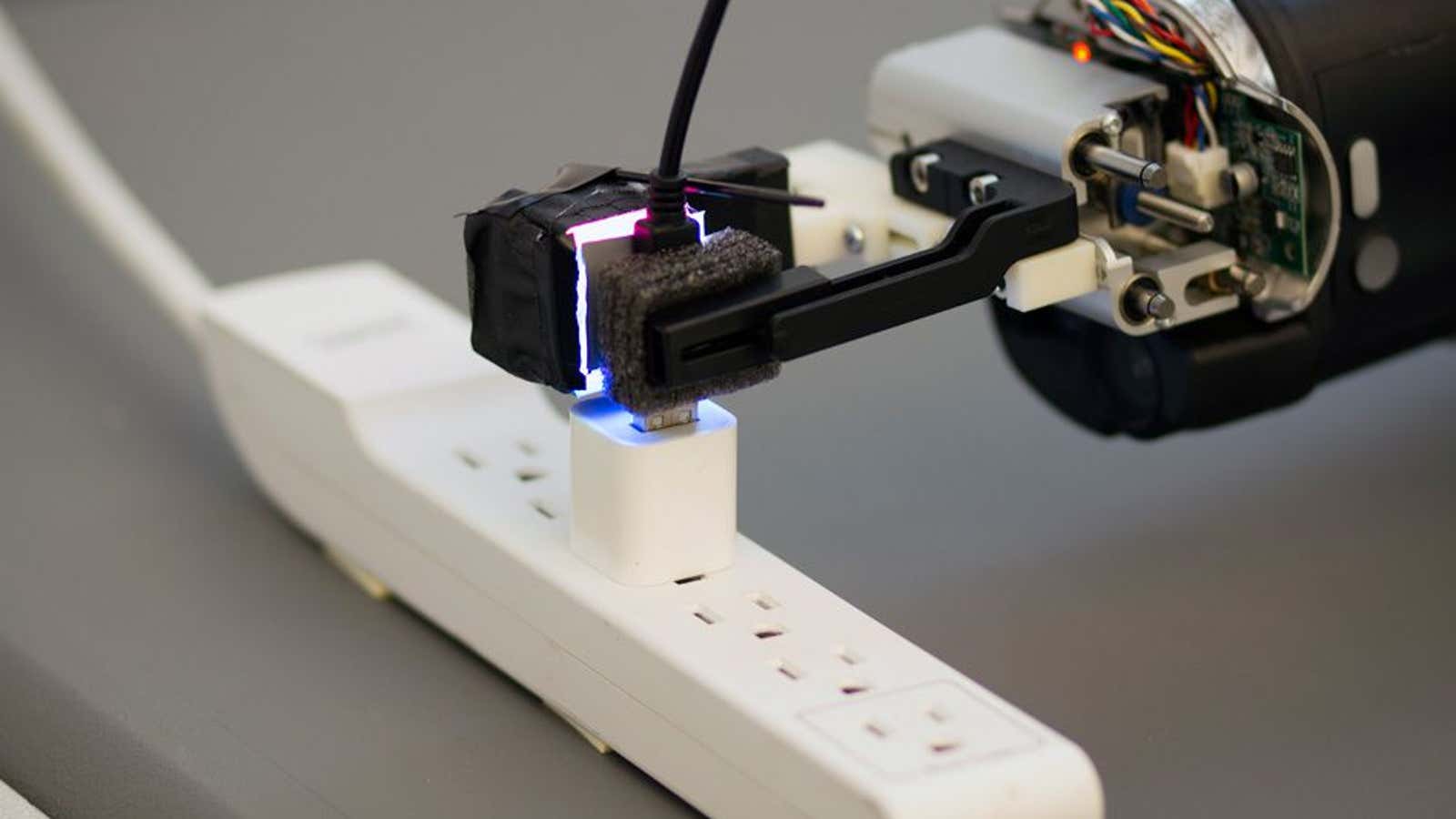

The new sensor has been housed in a box that flashes different kinds of light on the sensor, allowing Adelson’s team to ”infer the three-dimensional structure of ridges or depressions of the surface against which the sensor is pressed.” Robots can move objects if they are precisely positioned. The team’s robot, using the modified GelSight sensor, can pick up a USB cable draped freely over a hook and insert it into a USB port that only tolerates a millimeter’s error.

“Having a fast optical sensor to do this kind of touch sensing is a novel idea,” Daniel Lee, a professor of electrical and systems engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, told MIT. “I think the way that they’re doing it with such low-cost components—using just basically colored LEDs and a standard camera—is quite interesting.”

One measure of human sensitivity to touch is that two bumps need to be at least a millimeter apart to be distinguishable. By that standard, the GelSight sensor on the robot is about 100 times more sensitive than a human finger.