What do you think of GE’s BULLETIN series? We’re running a short, 30-second survey – click here to take it.

India continues to struggle with providing basic medical care for its citizens. After two decades of strong economic growth, life expectancy in India falls short of most developed and developing nations; the infant mortality rate is three times higher than China’s and seven times higher than the U.S.

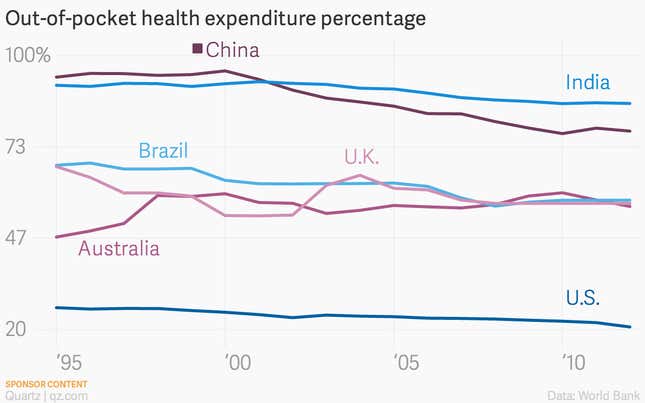

A primary cause of this national struggle is accessibility. It is estimated that 600 million people in India are with little or no access to healthcare, many of them in rural locations. The cost of care is also keeping citizens from getting proper treatment, or any treatment at all. Rising private healthcare costs and a lack of quality, affordable alternatives are forcing high out-of-pocket expenses that exacerbate the problem. India’s healthcare system has been described as being on “life support,” with distinct gaps in equitable access and affordability crossing all regions and communities. Innovation at hospitals and new government programs, though, are showing promise that care will be more freely available and future generations will be leading longer, healthier lives.

Affordability and privatised care

Nearly two-thirds of Indian households seek healthcare from the private medical sector, and that choice is further on the rise. Many years of neglect, worker absenteeism, long wait times, shortages of supplies, and absence of diagnostic facilities are why patients are avoiding public health facilities. Visits to private practices, though, often lead to out-of-pocket expenses that most patients can’t afford, causing to a significant percentage of the population to go without care.

Despite the emergence of a number of health insurance programmes and schemes, only 5% of households report that a household member has coverage of any kind. India’s Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2012-2017) has outlined a vision for a system of Universal Health Coverage with the envisaging of a large role for the private sector and a cooperative public-private partnership to achieve India’s healthcare goals. The plan has received much criticism, however, for an apparent limited understanding of universal healthcare and a diluted commitment to public expenditures on health.

Those in support of reform are galvanized around the need for a focus on all dimensions of healthcare and an approach that ensures the highest possible access along with education and awareness of health concerns. This includes sustainable policy solutions for healthcare financing, infrastructure to fill resource gaps, enablement of quality care through a regulatory system, and greater government spending on healthcare to cut out-of-pocket expenses. Acting together, these improvements may significantly cut costs and increase survival rates by focusing on the most crucial moment for a patient: getting the diagnoses right the first time and administering the right treatment.

Accessibility

Rural communities across the country are without access to hospitals and clinics. Inhabitants that seek out treatment face long-distance travel, and often settle for care at the most convenient locations instead of finding the specialised care their conditions demand. Some of these patients are further inconvenienced by loss of a day’s wages to receive attention.

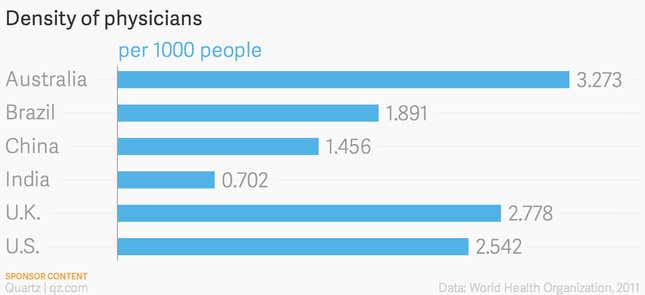

Much of the problem is manpower. There are 750,000 doctors in India, which amounts to only one for every 1,425 people. (Until recently, many doctors would avoid rural service, leaving an even greater void in the places that needed it most.) With an eye towards closing this gap, the Medical Council of India has discussed the idea of shortening the curriculum for students receiving Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degrees, delivering them into the field a year early. The state of gynecological oncology illustrates this desperate need for talent. There are more than 70,000 new cases of cervical cancer, the second-most widespread type of cancer among Indian women, reported each year; India produces only one gynecological cancer specialist each year to treat that mass of diagnoses.

The other problem is infrastructure and equipment: without water, power, and proper facilities, effective care is difficult to provide.

There are minds at work figuring out how to improve the rural dilemma. A paper commissioned by UNICEF India (PDF) recommends increasing availability of specialist health services in remote locations by testing improved communication technologies, monetary incentive structures for doctors providing rural service, and increased numbers of post-graduate seats in medical colleges.

Frugal innovation

Despite the immense challenges plaguing the Indian healthcare system, several Indian hospitals are working with globally trained specialists on the implementation of innovative solutions that provide affordable care to scale. The business model of these hospitals relies on drawing in wealthy patients to subsidise care to patients with low income. The result of this approach is that the hospitals can sustain their operations through their own revenue generation instead of relying upon government subsidies or insurance reimbursements.

According to data gathered by HCG and the National Cancer Institute’s SEER program, some Indian hospitals are able to provide high-quality care, comparing favorably to benchmarks of top institutions in the U.K. and U.S., at ultralow prices. One of these is Apollo Health City in Hyderabad, which outperformed international standards for positive outcomes associated with coronary, knee, and prostrate surgery. This trend is partially due to reduced cost of labor, but primarily because of innovative cost-effective solutions, ranging from use of the efficient hub-and-spoke facility model to ensuring the maximum life span of equipment through constant maintenance.

Innovations at these Indian hospitals are not simply the result of a calculated design. They are achieved from adaptation, experimentation, and co-creation. This strategy–borne out of the necessity to find solutions that will be effective in the Indian context–is empowering physicians and getting diagnoses right, at increasingly affordable rates.

Given the pressure on healthcare systems across the world, these emerging innovations–particularly in a developing country like India–offer important insights on how to tackle the rising costs of healthcare. Soon it could become common for the West to look East for best medical practices.

The GE Innovation series

We’re running a short, 30-second survey about GE’s BULLETINs. Click here to take it.

See what GE is doing in Bangalore, Shanghai, and New York to innovate on oil and gas technology

Reducing India’s dependence on foreign oil and gas

The great hope for India’s energy independence is waiting under water

Explore the full archive here.

This article was produced on behalf of GE by the Quartz marketing team and not by the Quartz editorial staff.