There will be a great deal of talk about India’s soft power over the next few days. Prime minister Narendra Modi, who will address the United Nations General Assembly on Friday, is likely to bring up the subject in several of his 35 engagements in New York and Washington. It is a subject close to Modi’s heart: He talked about it long before he became India’s leader, arguing that soft power can be harnessed to build “Brand India” and benefit the country.

Color me skeptical. There’s no question India does possess substantial soft power: I know this because it once saved my life. But India’s influence on the hearts and minds of people everywhere is not a commodity that can be packaged and marketed in the manner Modi suggests. India’s soft power has evolved organically, without much help from its governments. Best, I think, to let it keep evolving that way.

What is soft power? It is often no more than a brilliant idea. The oldest example of India’s soft power I can think of is Buddhism, a philosophy—and eventually a faith—articulated by Gautama Siddhartha over 2,500 years ago, which then spread across Asia. Soft power can also be projected by hard objects: To the Romans, expensive Indian spices and fabrics conjured up images of a land of wealth and luxury.

In the modern era, the most powerful expression of Indian soft power was, again, a galvanizing idea: Mahatma Gandhi’s notion of nonviolent resistance to colonial rule captured the world’s imagination and inspired others who struggled against oppression, from Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela to Lech Walesa and Aung San Suu Kyi.

In the 1950s, it was Jawaharlal Nehru’s turn to burnish India’s international image with an idea of his own: non-alignment. Working with other Third World leaders (the expression ‘developing world’ had not yet been coined) like Egypt’s Gamal Nasser and Indonesia’s Sukarno, Nehru argued that countries needn’t take sides in the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union—the geopolitical equivalent of the Buddha’s “Middle Path,” if you will. It was too utopian to last long, but while it did, India basked in the attention.

Around the same time, Indian cinema began to attract fans across the world, especially in Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. In 1957, ‘Mother India’ became an international hit, one of the first not produced in the US or Europe. Actor-director Raj Kapoor was mobbed on the streets of Moscow, his brother Shammi became a hearththrob in Baghdad. (In 2003, when three Indian truck drivers were kidnapped in southern Iraq, a tribal sheikh offered to arrange their release—if he got a phone call from his favorite Indian actress from the 1960s, Asha Parekh.) In the 1970s, Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan demonstrated the same cross-border appeal.

In British and American cinema, India would for decades be stereotyped as an exotic place—home of Sabu, The Elephant Boy, or the backdrop for a TV series about the British Raj. India occasionally featured in the Western cultural scene, in the form of Ravi Shankar and his sitars or an assortment of Hindu godmen offering spiritual sustenance, usually in exchange for very earthly remuneration. The bundi, or sleeveless Nehru coat, that Modi has made his signature look, also enjoyed a brief moment in the fashion scene.

The next expression of Indian soft power was likely invented in Britain: chicken tikka masala. The spicy-sauced dish quickly (and inexplicably) became the national dish of multicultural UK. Indian restaurants sprang up all over the country, and soon around the world. In the US, people who couldn’t place the country on a map could taste India—and presumably, make a dash for the restrooms.

India also began to crop up more frequently in the Western cultural scene, perhaps most memorably in the form of the Simpsons character Apu Nahaseemapetilon, owner of the Kwik-E-Mart.

But even as the Simpsons was becoming a hit show, a global scare was about to have a dramatic impact on India’s image in the world. It was called the Millennium Bug, or the Y2K Problem—the notion that a glitch in software code would bring every computer in the world to a halt at midnight on Dec 31, 1999. Starting in the late 1980s, tens of thousands of Indian engineers and programmers fanned across the world (and especially in the US) to kill the bug and save the world.

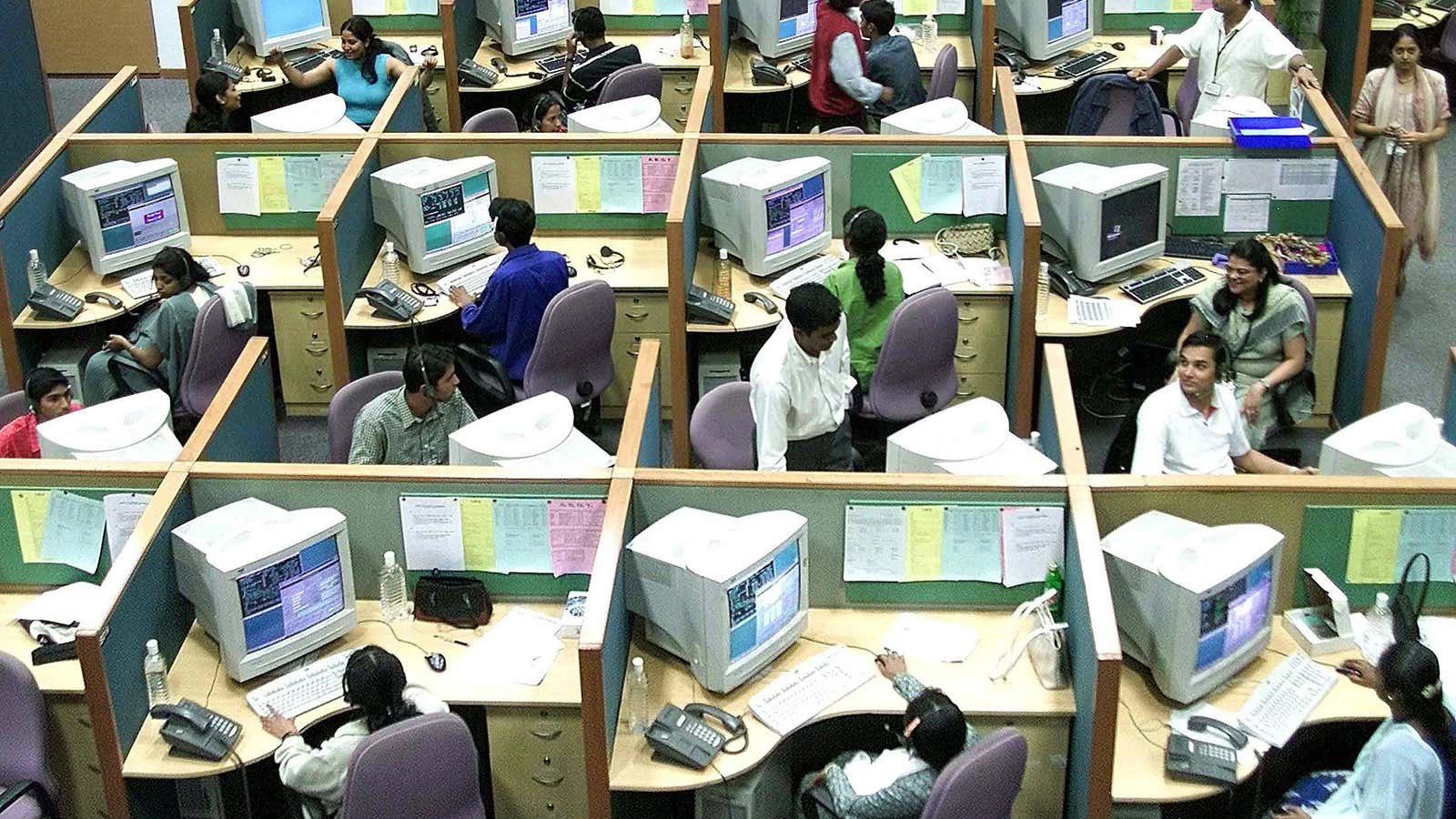

Suddenly, Indians were being seen as problem-solvers, technically skilled and reliable. When 2000 came and went without the global shutdown, the world began to outsource other problems to India. Call centers (“Hello, this is Charlie. How can I help you with your insurance needs today?”) exposed more and more people to Indians—and to occasionally impenetrable Indian accents. Business process outsoucing, or BPO, now brings India $21 billion in annual revenues.

In the American cultural zeitgeist, meanwhile, Indians have been popping up everywhere: Mindy Kaling in The Mindy Project, Archie Panjabi in The Good Wife, and Kunal Nayyar in Big Bang Theory are only a few examples. And notice how the roles have changed—Mindy plays a doctor, Panjabi an investigator, and Nayyar’s Raj Koothrappali is an astrophysicist.

That’s a long, long way from Sabu and Apu.

Other expressions of Indian soft power now abound: Bikram yoga, Bollywood dancercise gyms, cricket’s Indian Premier League. And here’s what they have in common: The Indian government had virtually nothing to do with their success. It’s no coincidence that the one instrument of Indian soft power that was actively promoted by government—non-alignment—is now a sad shadow of the original conception.

There’s a lesson there for Narendra Modi.

Note: This essay is based on a speech I gave on Sept 16, at the NASSCOM-BPM Summit in Bangalore.