The BlackBerry was the first truly modern smartphone, the king of Personal Information Management On The Go. But under its modern presentation lurked its most fatal flaw, a software engine that couldn’t be adapted to the Smartphone 2.0 era.

Jet-lagged in New York City on January 4th 2007, just back from New Year’s in Paris, I left my West 54th Street hotel around 6am in search of coffee. At the corner of the Avenue of the Americas, I saw glowing Starbucks stores in every direction. I walked to the nearest one and lined up to get my first ration of the sacred fluid. Ahead of me, behind me, and on down the line, everyone held a BlackBerry, checking email and BBM messages, wearing a serious but professional frown. The BlackBerry was the de rigueur smartphone for bankers, lawyers, accountants, and anyone else who, like me, wanted to be seen as a four-star businessperson.

Five days later, on January 9th, Steve Jobs walked on stage holding an iPhone—and the era of the BlackBerry, the Starbucks of smartphones, would soon be over. Even if it took three years for BlackBerry sales to start their plunge, the iPhone introduction truly was a turning point In BlackBerry’s life.

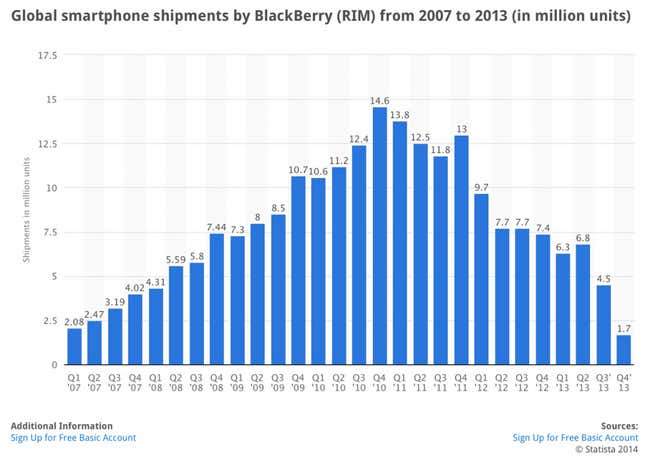

RIM (as the company was once called) shipped 2 million BlackBerries in the first quarter of 2007 and quickly ascended to a peak of 14.6 million units by Q4 2010, only to fall back to pre-2007 levels by the end of 2013:

Last week, BlackBerry Limited (now the name of the company) released its latest quarterly numbers and they are not good: Revenue plunged to $916 million vs. $1.57 billion a year ago (-42%); the company lost $207 million and shipped just 2.1 million smartphones, more than a half-million shy of the Q1 2007 number. For reference, IDC tells us that the smartphone industry shipped about 300 million units in the second quarter of 2014, with Android and iOS devices accounting for 96% of the global market.

Explanations abound for BlackBerry’s precipitous fall.

Many focus on the company’s leaders, with ex-CEO Jim Balsillie and RIM founder Mike Lazaridis taking the brunt of the criticism. In a March 2011 Monday Note uncharitably titled The Inmates Have Taken Over The Asylum, I quoted the colorful but enigmatic Jim Balsillie speaking in tongues:

“There’s tremendous turbulence in the ecosystem, of course, in mobility. And that’s sort of an obvious thing, but also there’s tremendous architectural contention at play. And so I’m going to really frame our mobile architectural distinction. We’ve taken two fundamentally different approaches in their causalness. It’s a causal difference, not just nuance. It’s not just a causal direction that I’m going to really articulate here—and feel free to go as deep as you want—it’s really as fundamental as causalness.”

This and a barely less-bizarre Lazaridis discussion of “application tonnage” led one to wonder what had happened to the two people who had so energetically led RIM/BlackBerry to the top of the industry. Where did they take the wrong turn? What was the cause of the panic in their disoriented statements?

Software. I call it the Apple ][ syndrome.

Once upon a time, the Apple ][ was a friendly, capable, well-loved computer. Its internal software was reliable because of its simplicity: The operating system launched applications and managed the machine’s eight-bit CPU, memory, and peripherals. But the Apple ][ software wasn’t built from the modular architecture that we see in modern operating systems, so it couldn’t adapt as Moore’s Law allowed more powerful processors. A radical change was needed. Hence the internecine war between the Apple ][ and Steve Jobs’ Mac group.

Similarly, the BlackBerry had a simple, robust software engine that helped the company sell millions of devices to the business community, as well as to lay consumers. I recall how my spouse marveled at the disappearance of the sync cable when I moved her from a Palm to a Blackberry and when she saw her data emails, calendar and address book effortless fly from her PC to her new smartphone. (And her PC mechanic was happy to be freed from Hotsync Not Working calls.)

But like the Apple ][, advances in hardware and heightened customer expectations outran the software engine’s ability to evolve.

This isn’t something that escaped RIM’s management. As recounted in a well-documented Globe and Mail story, Lazaridis quickly realized what he was against:

“Mike Lazaridis was at home on his treadmill and watching television when he first saw the Apple iPhone in early 2007. There were a few things he didn’t understand about the product. So, that summer, he pried one open to look inside and was shocked. It was like Apple had stuffed a Mac computer into a cellphone, he thought.

[…] the iPhone was a device that broke all the rules. The operating system alone took up 700 megabytes of memory, and the device used two processors. The entire BlackBerry ran on one processor and used 32 MB. Unlike the BlackBerry, the iPhone had a fully Internet-capable browser.”

So at a very early stage in the shift to the Smartphone 2.0 era, RIM understood the nature and extent of its problem: BlackBerry’s serviceable but outdated software engine was up against a much more capable architecture. The BlackBerry was a generation behind.

It wasn’t until 2010 that RIM acquired QNX, a “Unix-ish” operating system that was first shipped in 1982 by Quantum Software Systems, founded by two Waterloo University students. Why did Lazaridis’ company take three years to act on the sharp, accurate recognition of its software problem? Three years were lost in attempts to tweak the old software engine, and in fights between Keyboard Forever! traditionalists and would-be adopters of a touch interface.

Adapting BlackBerry’s applications to QNX was more complicated than just fitting a new software engine into RIM’s product line. To start with, QNX didn’t have the thick layer of frameworks developers depend on to write their applications. These frameworks, which make up most of the 700 megabytes Lazaridis saw in the iPhone’s software engine, had to be rebuilt on top of a system that was well-respected in the real-time automotive, medical, and entertainment segment, but that was ill-suited for “normal” use.

To complicate things, the company had to struggle with its legacy, with existing applications and services. Which ones do we update for the new OS? Which ones need to be rewritten from scratch? And which ones do we drop entirely?

In reality, RIM was much more than three years behind iOS (and, later, Android). Depending on whom we listen to, the 2007 iPhone didn’t just didn’t stand on a modern (if incomplete) OS, it stood on three to five years of development, of trial and error.

BlackBerry had lost the software battle before it could even be fought.

All other factors that are invoked in explaining BlackBerry’s fall—company culture, hardware misdirections, loss of engineering talent—pale compared to the fundamentally unwinnable software battle.

(A side note: Two other players, Palm and Nokia, lost the battle for the same reason. Encumbered by once-successful legacy platforms, they succumbed to the fresh approach taken by Android and iOS.)

Now under turnaround management, BlackBerry is looking for an exit. John Chen, the company’s new CEO, comes with a storied résumé that includes turning around database company Sybase and selling it to SAP in 2012. Surely, such an experienced executive doesn’t believe that the new keyboard-based BlackBerry Passport (or its Porsche Design sibling) can be the solution:

Beyond serving the needs or wants of diehard keyboard-only users, it’s hard to see the Passport gaining a foothold in the marketplace. Tepid reviews don’t help (“The Passport just doesn’t offer the tools I need to get my work done”); Android compatibility is a kludge; developers busy writing code for the two leading platforms won’t commit.

Chen, never departing from his optimistic script, touts BlackBerry’s security, Mobile Device Management, and the QNX operating system licenses for embedded industry applications.

None of this will move the needle in an appreciable way. And, because BlackBerry’s future is seen as uncertain, corporate customers who once used BlackBerry’s communication, security, and fleet management services continue to abandon their old supplier and turn to the likes of IBM and Good Technology.

The company isn’t in danger of a sudden financial death: Chen has more than $3 billion in cash at his disposal and the company burns about $35 million of it every quarter. BlackBerry’s current stock price says the company is worth about $5 billion, $2 billion more than its cash position. Therefore, Chen’s endgame is to sell the company, either whole or, more likely, in parts (IP portfolio, QNX OS…) for more than $2 billion net of cash.

Wall Street knows this, corporate customers know this, carriers looking at selling Passports and some services know this. And potential body-parts buyers know this as well…and wait.

It’s not going to be pretty.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.