Defaulting on your student loans is a good thing to avoid.

So when the US Department of Education released its latest batch of data on student loan defaults last month, it was good news that overall default rates fell to 13.7% from 14.7%. (Two years ago—the first time these numbers were released—the rate was 13.4%.)

It’s not surprising to see a drop in the rates. After all, we passed through the Great Recession and emerged on the other side. Now that jobs are more plentiful and the economy has healed quite a bit, it makes sense that it’s easier to avoid default.

But at some schools—including recognizable, large public schools—the needle moved in the opposite direction: default rates rose between two years ago and last year, and again between last year and this year.

What does it tell us when a school’s default rate jumps? It’s hard to know. Looking at the lists below, it’s obvious that there are certain regional concentrations.

Does that tell us something about how those regions have fared during the economic recovery? Many of the schools on this list are deep in the heart of the US industrial regional known as the Rust Belt, which was particularly hard hit by the recession.

“When the latest recession began in 2008, we, like other institutions, saw a significant influx of new students, a number of which were then not able to find jobs commensurate with their additional education, and others utilizing college as a source of loans they could not otherwise get to finance their living circumstances,” said Rob Denson, president of Des Moines Area Community College, which saw default rates surge in recent years. “These are the loans we believe are most likely now in default.” Denson added that he expects default rates to drop back down to pre-2008 levels in coming years.

On the other hand, others suggest tough economic conditions aren’t the only explanation for increases in student defaults.

“I’m not totally convinced that defaults are driven by people who can’t afford the loans,” said Jason Delisle, director of the Federal Education Budget Project at New America, a think tank. (You can get a sense of its funders here.) He pointed out that the government seizes $2 billion per year (pdf, p.17) in tax refunds from student loan defaulters. If defaulters are all broke, then where does that $2 billion come from?

“I think it’s a much more complicated story,” he says.

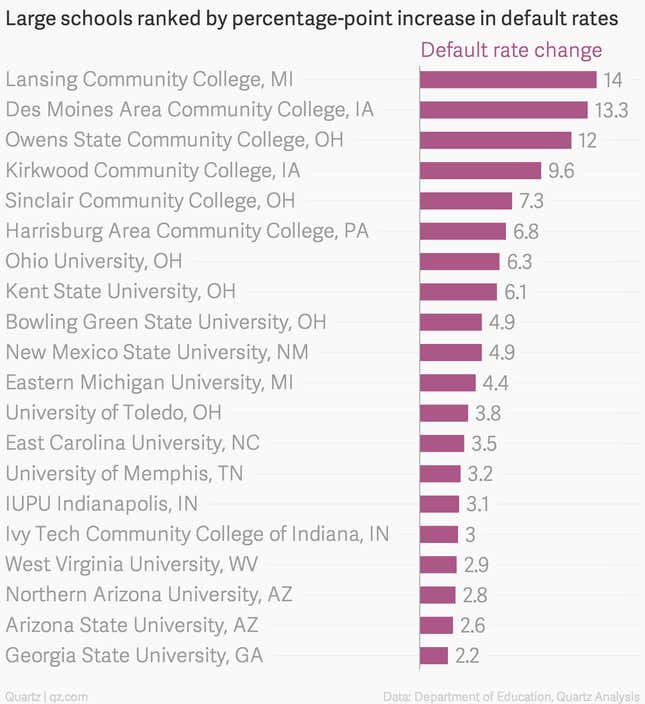

That said, here are the large schools where the default situation deteriorated the most in the past three years. (That is, they had the largest percentage-point increase in default rates.) This list includes schools that had at least 5,000 students enter repayment in 2011.

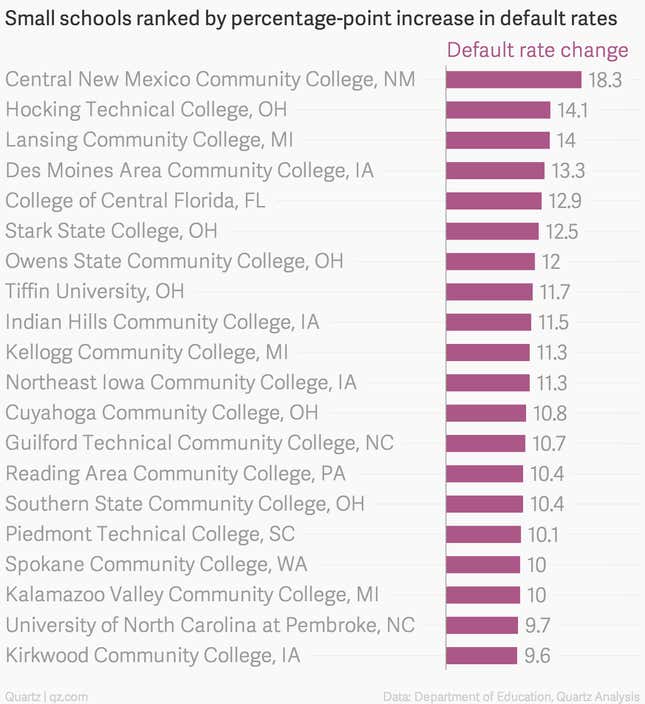

Here’s a list of small schools that showed the biggest increases. (All of them are public except for Tiffin University, which attributed their jump in defaults to an online degree offering they have since abandoned.) This list consists of schools that had at least 1,000 students enter repayment in 2011. For the record, we didn’t include for-profit schools—which have a well-known problem with egregiously high default rates—in our analysis, in an an effort to try to focus on more conventional colleges and universities.

The data here reflect the latest 2011 three-year default rates for all accredited American colleges. That number measures, by school, the percentage of federal student loans that were supposed to get repaid beginning in fiscal 2011 but went into default—meaning the debtor went 270 days without payment—some time in the next three years. This number doesn’t capture those who are teetering on the verge of default or who have entered deference or forbearance programs, which let debtors temporarily halt payments without defaulting. It also doesn’t account for the fact that some schools attract more low-income students who are vulnerable to default or the fact that some schools just happen to be in economically depressed areas.