High-frequency trading doesn’t hurt the little guy

The stock market has become a scary place. Many days we see large swings in stock prices and it seems that each week brings another scandal involving high finance. Meanwhile, more people own stock than ever before. How can most of us compete with traders on Wall Street who use computer programs that buy and sell thousands of stocks within a fraction of a second? Is this fair to the little guy investing his life savings?

The stock market has become a scary place. Many days we see large swings in stock prices and it seems that each week brings another scandal involving high finance. Meanwhile, more people own stock than ever before. How can most of us compete with traders on Wall Street who use computer programs that buy and sell thousands of stocks within a fraction of a second? Is this fair to the little guy investing his life savings?

The answer is yes. We are all in the same market and stock investing is not necessarily a zero-sum game.

Since the 1960s, investment in the stock market has changed. In 1962, only about 24% of people owned stock and most held shares in fewer than four companies. Most people who owned stock were wealthy. Since then, markets have become more democratic. According to the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances, about half of Americans own stock today. Most, 86% of equity holders, own stock through their retirement accounts. Stock portfolios are also better diversified; many investors own shares in hundreds or thousands of companies through mutual and index funds. Wealthier people are still more likely to own stock, but when you include retirement accounts, more middle-income folks now own stock as well.

Different kinds of investing

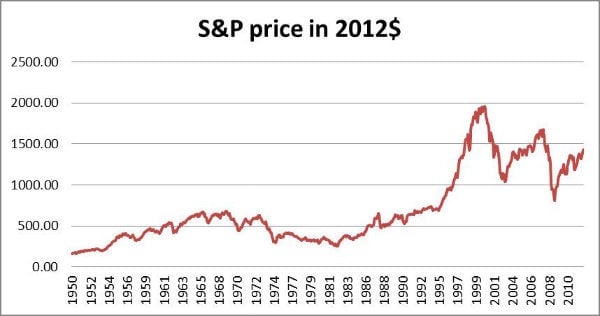

It’s important to make the distinction between investing to build wealth, what most people do with their retirement account, and speculation, what goes on at hedge funds or large banks. Long-term investing is not betting on whether a stock goes up or down today; it is betting that stocks will increase over the long-term. A stock price reflects information about a company’s future profitability. Owning a well-diversified portfolio of many different companies, and holding it for decades, is taking a bet that the global economy will continue to grow over the long term. That gives you a share in long-term growth and prosperity. This is not zero-sum investing. If the economy grows your portfolio probability will too. Historically, this is a good bet to make. Below is the price of the S&P 500 from 1950 to today:

The upward trend, which is the normal market return, represents economy-wide wealth creation. Though lately, markets have become more volatile. Long-term investors may get the benefit of long-term growth, but must tolerate more day-to-day fluctuations of the market. More volatility increases the probability that investors will lose money in the stock market.

Other investors have a different agenda. Hedge funds try to earn more than the normal market return and not lose money when the market is down. This often requires speculation, which is taking a position that a particular stock’s price will rise or fall within a certain period of time. The first to see a mispricing and act on it makes the most profit. This profit is in excess of the normal market return that the rest of us earn. The excess profit is finite, so competition for it is a zero-sum game. But that’s not at odds with the typical small, buy-and-hold investor who earns the normal market return.

Enter: high frequency trading

Speculation like this has also always existed in markets, but the nature of it has also changed. Now, some speculators use computer programs that trade thousands of stocks within a fraction of a second. This is known as High Frequency Trading (HFT). It may describe only about 2% of investors, but it can account for between 50% to 70% of all trades. It’s recently attracted the attention of policy-makers in Germany, Australia, Canada and now America. German law-markers are calling for restrictions on such trading in European markets.

There is concern that high-frequency trading is unfair because the trading is so fast that the profits are taken before others have a chance to trade. Joe Saluzzi, who co-authored the book, Broken Markets—How High Frequency Trading and Predatory Practices on Wall Street are Destroying Investor Confidence, is concerned that this trading has created an “un-level playing field” where a select group of investors access and trade on information, beating out other investors. He’s concerned that investing has become an “arms race.” In order to compete in today’s markets, as an active investor, it seems you must have access to high-frequency trading. Any investor who lacks the sophistication or technology to compete loses. This includes pension funds, less sophisticated mutual funds, and anyone who regularly trades individual stocks or exchange traded funds.

But certain investors have always been luckier than others or had better proximity to markets. High-frequency trading is, in many ways, the modern evolution of what’s always existed. Also, if you are not trying to compete with hedge funds for that extra-market return, you don’t necessarily lose when high-frequency strategies make money. You may even benefit from it. Quartz’s Simone Foxman recently pointed out: High-frequency trading can be good for long-term investors by enhancing liquidity and narrowing spreads.

Market makers

This is because—as Joe Ratterman, president and CEO of BATS Global Markets, America’s third largest stock exchange, explains—most high-frequency trading is market-making. When you want to buy or sell a stock you need someone else to take the other side of that transaction, by agreeing to sell or buy that same stock. The odds that, at any given moment, there exists a seller and buyer who’ll agree to the same price is slim. So markets are lubricated by traders known as market makers. They post orders to buy and sell certain securities. Suppose the market maker thinks a share of Microsoft is worth $25.11. They will offer to sell a share of it for $25.12 and offer to buy it at $25.10.

The profit they make is the difference between these two prices, known as the spread. The market maker earns money the same way a car salesman does. A car dealer does not speculate whether car prices will go up or down. His revenue comes from the difference between the price a manufacturer charges him for the car and what a customer will pay him for it. It’s similar for the market maker, the smaller the spread the smaller their profit, but the less you, the average investor pays.

You must pay something for the ability to sell or buy a share whenever you want. But because high-frequency trading means larger trade volumes, market makers require smaller spreads to be profitable. According to a 2010 report from the Kauffman Foundation, in 1998 a market maker netted 4 cents in profit for every share traded. The typical HFT today nets 7/100 of a cent or less. This means the rest of us pay less for our transactions. Says financial journalist Felix Salmon:

After all, high-frequency trading has been genuinely wonderful for small investors like you and me. We might not be particularly clever, but when we put in an order to buy this or sell that, the order gets filled immediately. We pay almost nothing in trading costs—just a few pounds, normally.

Ratterman surveyed the nature of transactions at his exchange, BATS, and found 36% could be classified as market-making, but just 10.4% were propriety trading, the speculation that goes on at large banks and hedge funds. He worries that attempts to hinder high-frequency trading will only discourage market-making and increase costs to small investors.

Reports of its demise have been exaggerated, Ratterman says, and many small HFT firms aren’t leaving the market. He believes we’re seeing lower lower trade volumes because other investors, like individuals and pension funds, have become skittish about investing in stocks. Perhaps some of that fear is due to the perception that high-frequency trading is not just unfair, but that it is damaging markets. The 2010 Flash Crash and Knight Capital fiasco last August resulted in large drops in stock prices that made no sense.

Prone to human infallibility

What exactly caused the Flash Crash is still a matter of debate, but some argue that HFT exacerbated the sudden, large drop in markets. The Knight Capital incident was the result of a bug in its high-frequency trading algorithm. That’s worrying because even if small, long-term investors are swimming in the shallow end, their money is in the same pool. If the market drops 9% in a few hours, so does your wealth. The reality is that any computer program written by a human will always have some glitch or may act unpredictably under certain tail cases. But this risk is largely borne by the owner of the program.

The Flash Crash and Knight Capital incidents validate how well markets do work. If an errant high-frequency trading program moves prices away from what they should be, others will enter the market and bid prices back. Stock prices largely recovered by the end of the trading day when the Flash Crash and Knight Capital glitch occurred. But Knight Capital’s share price is still less than a third of what it was pre-glitch, on Aug. 1. Earlier this year Ratterman’s exchange, BATS, initial public offering was botched because of a bug in its trading software. In the end, BATS had to withdraw from the market and stay private, and as Ratterman says “we were the one who paid the price for our bug in terms of liquidity (from not being a public firm).”

High-frequency trading programs can be profitable, but they can be very risky. Ratterman observed that the nature of electronic trading, not just HFT, means potentially catastrophic bugs rear themselves fairly regularly, but safety guards, or just well-functioning markets, correct the problem before most of us notice it. Yet while computer programs are fallible, so is the judgment of individual traders who are prone to over-confidence and skewed incentives.

Ratterman believes the rush to crackdown on high-frequency trading is misguided and will ultimately pose a large cost to small investors. Regulation is meant to protect from ill-intent, and HFT is merely a method, though he agrees there should be safe guards in place for the inevitable bugs that occur. After the Flash Crash, circuit breakers, which stop trading when a price moves too much, were introduced for individual stocks. Next year there will be limit-up limit-down bands, which will pause trading when stock prices fall in or out of the band.

How HFT will ultimately transform markets is still not totally understood. Regulation must keep up with the latest technology to spot potential sources of systemic risk or illegal behavior. The stock market and the nature of investing constantly evolve with technology. In many ways technology has made finance more democratic from wider, cheaper, better-diversified stock ownership while speculation has gotten more cut-throat and competitive. The market allows for both of these investors to coexist.