Online advertising—the business that powers much of the internet—has a fundamental problem. And Facebook thinks it has a solution.

Online ads were built on a beguiling promise: For the first time, advertisers would know exactly how many people saw their ads, how many bought something as a result, and thus, how well the ads were working. The Economist in 2006 summed up the optimism: “Thanks to the power of the internet, advertising is becoming less wasteful and its value more measurable.”

Today, advertisers are back to complaining that they don’t know where their money goes or whether it works. Half the ads on the internet are never seen by a human. And the rise of mobile is making it harder to track people, because mobile apps don’t accept cookies—the small files your web browser saves when you visit a website, which the website then uses to identify you on your next visit.

Measuring ads’ effectiveness is also becoming harder as display advertising grows. Unlike direct-response ads (the ones that show up when you do a web search, for instance), display ads aren’t necessarily meant to be clicked on, but rather—like ads on TV or in magazines—to make you aware of a brand or product. Unless there is a direct click, however, how can you prove that an ad for a new book made someone buy it? What if he did it on another day, or using a different computer, or even went into a bookstore? And such display ads will grow at nearly 15% a year in the US and over 10% a year in Europe, according to Forrester.

Facebook has already solved this problem for its own social network. And last week it launched a new and improved version of Atlas, an ad-serving platform it bought from Microsoft for $100 million last year, with which it proposes to solve the problem for the internet at large.

Your new best friend

Here’s an example of the problem in action. While lounging on the couch at home, browsing Facebook on your phone, you see an ad for some shoes. A couple of weeks later at work, you suddenly remember the shoes, log on at your work computer, and buy them. In most cases, the ad server has no idea that the person who bought the shoes was the same person who saw the ad. From the shoe-seller’s point of view, the ad was useless.

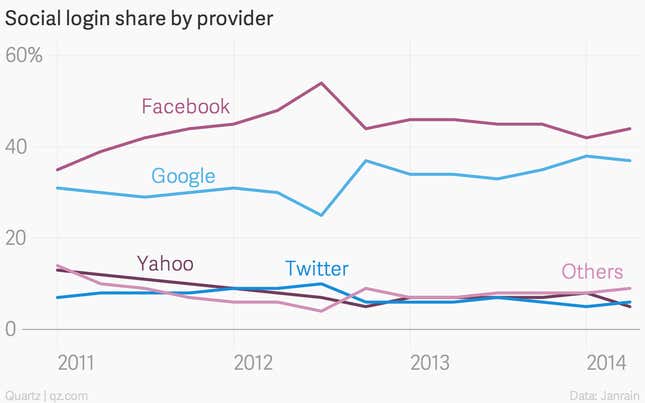

But Facebook has the one thing, at scale, that no other web firm barring Google can boast: your identity. When you log into Facebook on a phone or computer, Facebook associates that device with your Facebook ID (a long number such as 444654488901592, Quartz’s Facebook ID). If you then use that device to visit a website that uses Facebook login or embeds a Facebook tracker, Facebook knows. Among sites that let you log in using a social network, Facebook is the leader:

What Atlas does is bring this ability to track individuals to ads on sites outside Facebook. Facebook and Atlas also pool the data with other sources—store loyalty cards, for example—through a data broker to match up those who have made purchases in stores. Facebook calls it “people-based marketing.” (Facebook stresses that the data are aggregated and anonymized, and that third parties do not see who has bought what.)

“Using the Facebook ID will tell us whether a woman 16-34 actually saw or interacted with the ad,” says Stefan Bardega, the chief digital officer at ZenithOptimedia, a media agency. Existing methods, he says, are technically difficult and expensive.

Solving the problem of measurement is essential for Facebook to grow. Google’s direct-response ads fulfil a demand: When you perform a search for ”cheap mobile phone,” Google knows you want to spend money and shows you ads accordingly. It’s easy for Google to show the ads worked: It just counts how many people clicked on them. Facebook, by contrast, must convince media planners—the people who buy ads—that its display ads create demand. The new measurement systems with Atlas help it prove that. As one Facebook marketing bigwig recently declared (paywall) to the New York Times, “We want to hold ourselves accountable for delivering results.”

“A huge step forward”

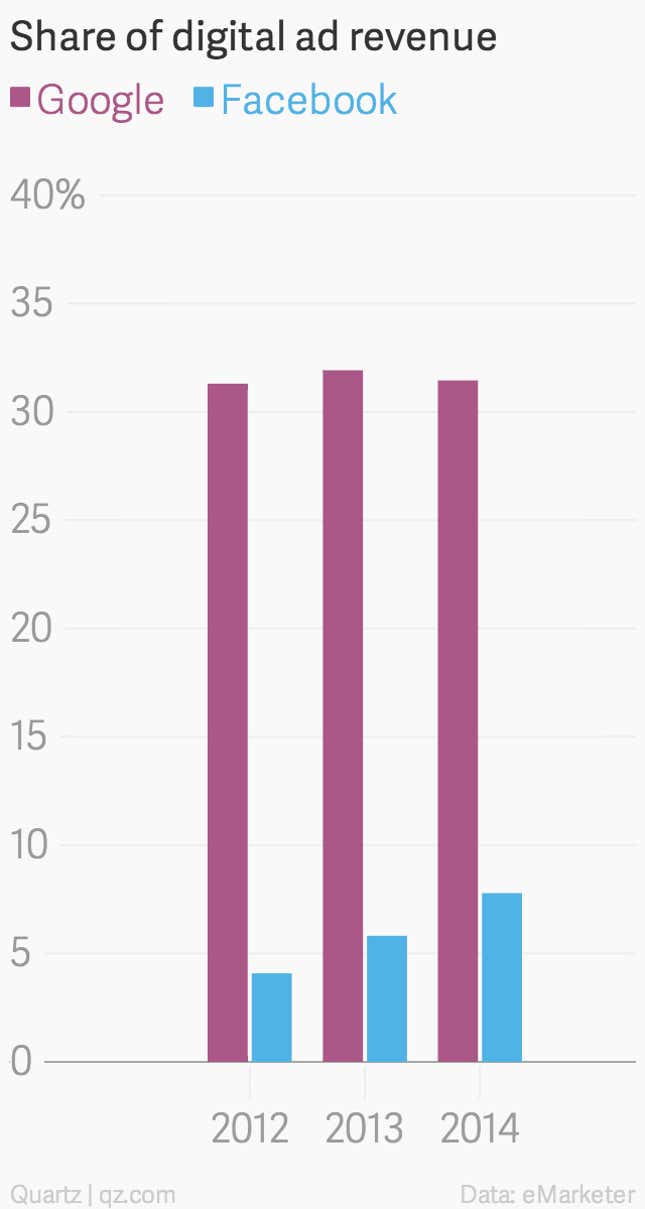

Atlas is a direct challenge to Google. Not only does Google dominate in direct-response ads; through its subsidiary Doubleclick, it runs the dominant ad network on the internet, taking one in every three dollars on digital ad revenue worldwide, according to eMarketer. Facebook’s share is just under 8%. But Facebook is growing fast. Its share has doubled in the past two years, while Google’s has stagnated.

Advertisers are excited about it. “They [Facebook] know your age and gender,” says Jonathan Nelson, who runs the digital arm of Omnicom, one of the largest advertising holding companies in the world. “So even just having those two bits of information is a huge step forward for people like us.” Ed Chater of Lithient, an ad tracking firm, says Atlas is “potentially a game changer.” Bardega calls it a “real win” for advertisers.

But there are caveats. The success of Atlas depends on Facebook’s reach. If 80% or more of the audience in any market use Facebook, Bardega says, the data it provides to Atlas can be considered robust. But in places like Russia, Facebook has a smaller share. “So for global businesses this may not be the right solution,” he says.

Moreover, advertisers are wary about backing an ad platform that depends on Facebook’s data to work, even though it’s run independently. By contrast, DoubleClick doesn’t rely on people continuing to use Google search in order to serve them ads and report the results.

There are other limitations too. Facebook’s new ad server “can only be used to view media tracked by Atlas, requiring the advertiser to switch to Atlas as their ad server,” points out Adit Abhyankar of Visual IQ, an ad attribution firm. Moreover, he adds, the results are limited to people who use Facebook across a variety of devices. And the reports are incomparable with those from other ad servers. Indeed, the lack of standards in online advertising remains a big headache for media buyers and ad networks alike.

Head to head with Google

“In the near term, I don’t anticipate seeing businesses flee in droves from Google DoubleClick to Facebook,” says Patrick Salyer, who runs Gigya, an identity management platform. “There will be a lot of interest, however, and once we start seeing results from early adopters, more businesses will start coming over and Google may very well start leaking revenue as a result.”

Google isn’t taking it lying down. The day after Facebook’s announcement, Google published a blog post announcing something not unlike what Atlas offers: “estimated cross-device conversions for display ads,” which works by using data from people who have previously signed in to Google, something the company is keen to promote.

But Google will find it tougher going than Facebook. It’s already facing a regulatory backlash over its privacy practices; the day of its announcement about cross-device conversions, a regulator in Germany ruled (paywall) that the company “has not been willing to abide by the legally binding rules and has refused to substantially improve the user’s controls” when it comes to combining user data to build a profile. Facebook has yet to face such a backlash, though it might yet.

Nor is Facebook Google’s only challenger. Twitter, which has until now reported underwhelming results from its ad products, is also making a big push into the identity game. According to The Information (paywall), a tech trade publication, Twitter plans to make it easier for app developers to allow users to log in with Twitter, giving it access to their movements outside the platform. Called Twitter Fabric, the product “reflects Twitter’s desire to be at the center of online ‘identity’,” writes Amir Efrati.

But the rise of centralized, powerful ad networks owned by companies that also control vast amounts of data worries some (paywall). “Advertisers are nervous about giving all their data to their main media providers,” says Lithient’s Chater. Startups are working on the problem too. These aren’t perfect, he says, but it suggests that the field is wide open and “has a lot more innovation to come.”

In other words, internet users are about to become embroiled in a giant battle to see who can best track their every move.