Ram Sewak Sharma is a silver-haired, straight-talking bureaucrat who spent much of the last five years working out of an office near New Delhi’s Connaught Place. Next door to him sat Nandan Nilekani, the former Infosys CEO.

Together, the two men built the world’s largest biometric identification programme, Aadhaar. Nilekani was chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) till he left to join politics, while Sharma served as director general and mission director.

Now, 59-year old Sharma is building an attendance system for India’s central government employees that is inexpensive, publicly available on the internet—and potentially, a simple tool that could revolutionise governance in the country.

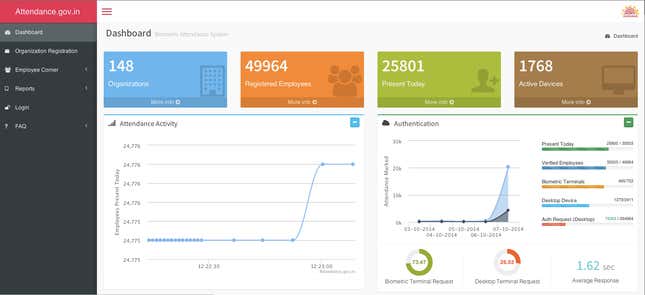

Based on the Aadhaar platform, attendance.gov.in is already online and currently undergoing testing with the attendance data of almost 50,000 government employees in New Delhi available online, in real-time.

The website (below) is a near-complete digital dashboard of employee attendance—it logs the entry and exit time, the exact device used and the average time the system took to authenticate an employee’s identity. The data is then organised by departments and ministries, before all the numbers from all of New Delhi are collated and displayed on the homepage.

The entire system is searchable, down to the names of individual central government employees, and all the data is available for download. And with that single step—making the entire platform publicly accessible—the government has introduced a level of accountability and transparency that India’s sprawling bureaucracy is unaccustomed to.

The system cannot track people leaving in between the check in and check out. But it can track chronic late comers. And the public reporting of data creates pressure on supervisors to ensure compliance.

But the origins of this biometric attendance system predate the current government. Instead, it all began when Sharma started work as the chief secretary of Jharkhand after leaving the Aadhaar project last year.

Made in Ranchi

After he took over as chief secretary, making him the top civil servant in the state, Sharma decided to deal with a well-chronicled administrative problem nearly every government office in the country deals with. “There were people spending huge amounts of time in office,” Sharma told Quartz, but there were “some jokers” who would barely come to work at the secretariat in Jharkhand’s capital, Ranchi. “This creates a huge disincentive for people to remain in office.”

The solution, he felt, was to create a “fool-proof” Aadhaar-based biometric attendance system that would be fast, reliable and publicly available. So, two employees of the UIDAI’s centre in the outskirts of Ranchi were brought in to craft the code and build the project from the ground up.

The idea was straightforward. Government employees who already had Aadhaar numbers would use their fingerprints—which were captured during the enrollment process—to register their attendance. Inexpensive biometric scanners would read their fingerprints, send the data to the UIDAI’s servers to authenticate them, confirm the match to the employee and finally, the attendance was displayed on a website.

In an office with wireless internet, the process was designed to take under two seconds, Sharma explained. And if a SIM card was used to connect via a mobile phone network, then the authentication would be completed in between five to six seconds.

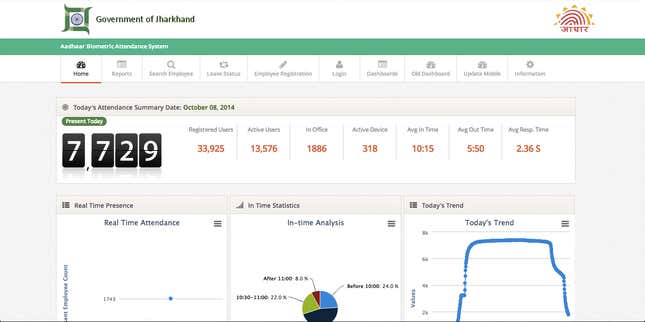

The result was attendance.jharkhand.gov.in. Launched in January 2014, Jharkhand’s pioneering online attendance system now tracks almost 34,000 employees, across 69 departments and 24 districts.

“Aadhaar is the key,” Sharma said, “In this, we’ve unbundled the entire system, and the infrastructure required is very small.”

Modified in Delhi

In May 2014, Sharma came back to Delhi as the secretary of information technology and communications. With degrees in mathematics from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur and computer science from the University of California (and a certificate in Russian), the 1978 batch IAS officer has over 30 years of experience across departments, including land revenue, transport, finance and human resource development.

Then, in late June, after Narendra Modi took over the government, Sharma and his department made a presentation to the prime minister. The Jharkhand prototype synced well with the new government’s Digital India programme. A decision was made to introduce biometric attendance to all central government offices in New Delhi by October 2014. “We started working around 20 July after receiving the formal communication from the PMO (prime minister’s office),” Sharma said.

Immediately Sharma brought in his crack, two-man UIDAI team from Ranchi that had built his Jharkhand platform, and got down to work. He identified 148 central government departments where the initial rollout would take place and all employees enrolled. Orders were placed for about 3,000 biometric devices and a so-called multi-tenancy website was built—this means the data for each ministry can be accessed if the URL is tweaked. So, while attendance.gov.in shows the attendance data for all the registered departments in New Delhi, mod.attendance.gov.in will open up the data for the ministry of defence (MoD).

In all, it costs around Rs3 crore ($490,000). “It’s still in the trial stage,” said Sharma, “And we are still getting feedback on it.”

One problem that the rollout can face is connectivity. Even in New Delhi, Sharma anticipates that there will be certain offices where connectivity will be an issue. But by using a combination of wireless internet and mobile phone networks, Sharma and his team hope that they’ll be able to ensure that the online authentication process is completed quick enough.

The eventual aim is to share the source code and the platform across state governments, who can then choose to implement it at various levels. In Jharkhand, Sharma explains, it has already been taken to the district level and could be even expanded to government-run hospitals and schools. It could be used, for instance, to track the number of mid-day meal beneficiaries in government schools and then compare that with the actual spending on the programme to ascertain leakages.

“This can become an extremely powerful tool for governance,” said Sharma, “This is only the beginning.”

With such unprecedented scrutiny, others in government, though, are likely to be less excited.