For decades, US beer drinkers have operated on the assumption that high-end, foreign brews come in bottles, while down-home, budget beers are packaged in flimsy, 12-oz. cans, the better for pounding and crushing.

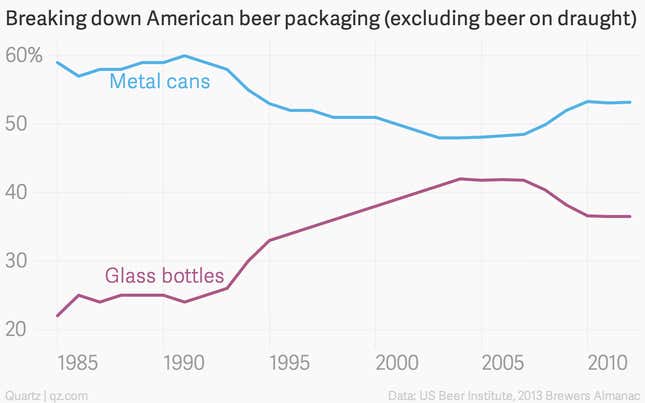

Though the cheap stuff never really went out of style, America’s consumption of beer in metal cans showed definite signs of waning in the early 1990s, while bottled beer picked up in popularity—a trend that lasted pretty much right through the economic go-go years leading up to the financial crisis.

But when a preference for canned beer reasserted itself a few years ago, it wasn’t just that the recession had US consumers falling back on cheaper options, or that hipsters were having a moment with the humble, blue-collar authenticity of cheap canned brews like Pabst Blue Ribbon.

There was another, influential group of consumers contributing to the trend, those who were propelling the US craft-beer movement by spending a bit more for small-batch, higher-quality, domestic brews—these beers were and are increasingly being packaged in cans, too.

Craft brewers love cans because they better protect beer from light and oxygen—two of a brew’s greatest enemies. Light exposure is what makes beer “skunk,” or smell awful. Light penetrates glass bottles, even the dark brown ones, but it doesn’t go through aluminum cans. And unlike a bottle cap, the seal on top of a can doesn’t let any oxygen in or out.

Concerns about canned beer bearing a metallic taste, which once was a factor that made bottles more appealing, should be long gone now. Decades ago, when the cans were made of tin and lined with lead, that was a valid worry. Today’s cans are made from aluminum and have a water-based polymer lining, though, so the beer doesn’t even touch the metal.

American craft brewer Oskar Blues is credited with kicking off the craft canning trend in 2002, with the success of its Dale’s Pale Ale .

California’s Sudwerk Brewing Co. has just begun to package its signature craft lager in aluminum cans. The 25-year-old company has never done this before, but co-owner Trenton Yackzan said, in a press release, that “the time was right for us to join the legion of craft brewers who have begun putting some of their beers in cans.” Rexam, one of the world’s largest beverage canning companies, is manufacturing the pale-yellow-and-green Sudwerk cans. A few years ago, Rexam was doing this for just a few craft brewers; in 2014, Sudwerk is one of more than 40 such accounts.

John Hargrove, an account director at packaging firm MWV in Richmond, Virginia, says the craft industry’s packaging preference is more about aluminum versus glass than it is cans versus bottles. Aluminum is recycled at a much higher rate than glass; it can be taken to venues—sporting events, campgrounds, beaches—where glass is not typically allowed; it’s not hard to manufacture in different sizes and shapes (the standard 12-ounce can is most popular, but brands can differentiate themselves with taller, shorter, or skinnier ones, as Red Bull has done); and it’s a better canvas for intricate designs than the paper labels wrapped around glass bottles.

People also perceive metal cans as being more conducive to ice cold beer. In any case, though, most beer aficionados make a habit of pouring their drink into tall glasses for sipping, no matter whether it comes from a bottle or can.

An earlier version of this post incorrectly referred to packaging firm MWV as MVW. (MWV stands for MeadWestvaco, the company’s legal name)