MONROVIA, LIBERIA—It was on a Monday morning some weeks ago in Monrovia, when hundreds of young Liberians flocked to the headquarters of a small, local NGO to join in the fight against Ebola. People used the opportunity to voice their anger: for months, schools and universities had been closed and there weren’t any jobs available. The young people asked the government not give the “Ebola jobs” to the international personnel that had finally started trickling in in higher numbers after six months of waiting.

Gloria Maya Terrick stood on the balcony of the NGO’s building and held up a sign that said: “Don’t Overlook Us.” Beneath her, the crowd was chanting. “We came to do awareness about Ebola,” the 20-year-old student said. “We try to fight Ebola and kick Ebola out of our country Liberia.“

Jamal Williams and his younger brother Isaiah had also come to the event. But for fear of contracting the virus in the huge gathering of strangers, they stood aside next to a wall. When the NGO failed to keep up with registering volunteers, the two of them left, disappointed.

Two days later, Jamal and Isaiah sat in a deserted bar at the beach of Monrovia. Isaiah, 23, said people don’t go out and they don’t really meet with friends anymore.

“Friends are all staying home,” Isaiah said. “There is no activity. We don’t socialize. We don’t go to the beach. We don’t go to the nightclub. We don’t go to school. We only go to church on a Sunday for a worship because at the church people take much precaution.”

Jamal said the crisis goes much deeper. Both brothers have had girlfriends for more than a year, but because of Ebola they barely see them and are not intimate. Most of the time, they talk on the phone.

“When she is at home or when she leaves home, I’m not aware of her well-being,“ Jamal said. “She does not know who I interact with. So I just encouraged her not coming around me and touching me. It’s better that we stay away from each other until we see a calm-down in this Ebola situation.”

For more than seven months, three West African countries have been in the grip of Ebola. It’s the worst outbreak since the disease was discovered almost 40 years ago. Liberia is the country that’s been hit the hardest. More than 2,300 Liberians have died. The nascent economy of the post-civil-war country is down, but Ebola causes more than death and economic stagnation. The highly infectious disease has built invisible barriers between people—human contact is strictly forbidden and deep mistrust rules the streets of Liberia.

Because of an 11pm curfew, Monrovia’s nightclubs open earlier than they used to. At Exodus bar around 6pm on a saturday night, you can hear loud music playing while the sun was still shining. Inside the club, people quietly sat around tables and no one danced. A partygoer said he wears long sleeves to avoid getting sick. Frequently, the deejay lowered the volume of the dancehall music to remind people of the risks through his microphone: “Well, Ebola is real. It’s here in Liberia.”

“As soon as it’s 6:30, 7 o’clock, we lower the music because we understand that when the music is high it gives people the momentum to wake up to dance,“said Steve Wiefueh, the club’s accountant. “Then we think, when they’re not hearing the heavy beat, they’ll just sit there, drink their beer and go home.

Nevertheless, some Monrovians kept coming. Viviane Gambah, a heavy woman in her thirties wearing a gold necklace that disappeared in the depth of her cleavage, sat outside on a terrace next to the club and downed some beers with her girlfriends.

“Today I just left my house because sometimes when we sit and think on this Ebola issue, we feel bad,“ she said in the melodic up-and-down of Liberian English. “And sometimes we really don’t know what to do. I just decided to come out and drink two or three bottles and go and sleep. But really I don’t dance. I don’t go to the club and dance. I don’t really associate myself.“

No dancing, no flirting, no touching, no kissing. No hugs, no handshaking, no backslapping. Not even for close friends.

It’s difficult for foreigners to understand how the imposed safe distance must feel for Liberians. Liberians interact much closer than Westerners do.

While Friday and Saturday nights in Monrovia are owned by nightclubs and entertainment centers, Sunday mornings belong to the church. But those, too, are in the grip of Ebola. It’s easy to think it’s the devil’s work.

Pastor Marcus Spear stood at the altar of his small episcopal church outside Monrovia and spoke to worshippers in a powerful voice:

“It also means that God has given you his Grace that today you are alive, whereas there are thousands of Liberians that have died. It’s intended for you to use your strengths and your resources, your energy, your muscles, your intellect to be able to tell other people how they can preserve, how they can conserve life. How they did work hard enough and observe the principles of hygiene and sanitation. By this, they cannot contract the Ebola virus.“

The congregation said Amen and joined in another gospel song.

The plump pastor, wearing white vestments and a navy-blue shawl, does not lead one of the extreme Pentecostal churches that mushroom almost everywhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, where worshippers sometimes theatrically jump up and down and lament their sins, sometimes roll over the floor and cry, and where priests put their hand on people’s foreheads to inject the Holy Spirit more directly. But even without such rituals, unthinkable during times of Ebola, pastor Marcus Spear says that his service, too, suffers a lot under Ebola. Because of Ebola, he doesn’t make a cross on people’s foreheads. Because of Ebola, they don’t shake hands for the Peace-Be-With-You salutation.

Chlorine water has become the new Holy Water, which is found in a green bucket at the entrance of his little church.

Ebola, Ebola, Ebola.

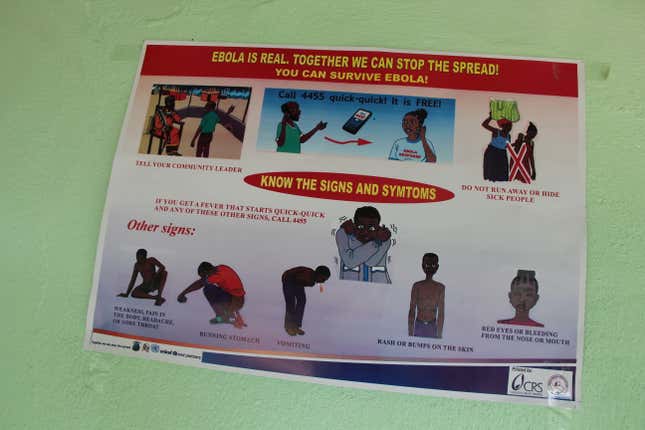

Street vendors have a hard time selling their snacks, except for things like oranges or kola nuts that one can easily be washed with chlorine before eating. Monrovia’s barbers, often men with two or three pairs of scissors on a table, are at the side of a street. Who wants to be touched by unknown hands? On every corner, posters warn of Ebola. Painted walls show the symptoms of the disease: Black men with red eyes, black men in pain. Black men, vomiting men. Black men with bloody diarrhea. Liberians are indoctrinated with fear. Ebola is on the radio, on TV, in the press.

Doctors Without Borders Ebola management center in the ELWA 3 district is one of the largest in the country. Isolated behind orange fences, men in yellow protection suits and goggles carry heavy, black body bags to a nearby tent. Not far away, weak-looking Ebola patients sat on garden chairs made of white plastic waiting for lunch.

Theresa Jones, a psychologist at the center said: “We’re finding it difficult to reintegrate the survivor children.” For fear of Ebola, communities refused to take them back in. Liberian health workers also suffer a lot. Bangalie V. Kamara works as a physician assistant at the Doctors Without Borders center. His job almost made his marriage crack: his wife of nearly 15 years doesn’t want him to work with Ebola patients. “In fact, she once told me that if I continue working there, I have to rent a different place where I will be isolated from the family.”

Eventually, his wife changed her mind; still, his family suffers. Parents had banned their children from playing with his daughter when they found out that he treats Ebola patients.

West Point is one of Monrovia’s poorest neighborhoods where nearly 75,000 people live. There is garbage lying everywhere on the street. Children play soccer on a muddy field. People say there is only one public latrine.

“Follow me,” said Theresa Sackyo, a Liberian health worker for a community-based NGO, and disappeared in a narrow alleyway. A man on the street had just given her a lead: Three dead bodies in a house at the beach. For fear of Ebola, neighbors had locked the home.

Sackyo rushed past corrugated iron-huts. Her yellow anorak rustled, wet sand squeaked under her black rubber boots. With every step, the roaring ocean came closer.

Sitting on a bench, seemingly untouched by the apparent danger, an old man leaned against the house of the dead. “So we would like to know these people who live in this home,” Sackyo said standing before him. “Because we’re not willing to lose all our people now to this awful disease that we have in Liberia.”

The old man said it would be best to talk to the landlord who had all the names, who would be returning tomorrow.

Does Sackyo face any problems with friends and family who avoid her because of her job? “No,” she said. “I’ve not experienced it yet.”

However, the entire district of West Point is avoided by the rest of Monrovia. Weeks ago, the government forced a quarantine on the area following a high number of Ebola deaths. Since then, people from West Point are treated like outcasts.

Marta Cowla, a fish vendor, sat on a wooden canoe on the beach of West Point. Behind her in the sand was a bowl with fresh fish from the sea.

“When we take to market and carry up, people do not want to buy because they say you all have Ebola here,” she said. “Business is not the way it used to be. So we end up carrying our business back to West Point.”

Jamal and Isaiah Williams also avoid West Point.

The two brothers live in a shabby house outside the center of the Liberian capital where they share a room with a friend for $20 a month. Isaiah is a student. Jamal works at a petrol station, which is, in fact, not more than a gas pump under a canopy on a roadside. They only have enough for two meals a day. Breakfast usually consists of rice and beans for 100 Liberian dollars, or $1.20.

In 1994, Liberia’s civil war separated the two brothers. Jamal fled with an aunt to a refugee camp in neighboring Guinea, Isaiah went off with rest of the family across Liberia fleeing from the rebels. Long marches of three, four miles a day together with thousands of people. No protection against rain or wild animals. Nine years later, the family was reunited. At the camp in Guinea, Jamal suffered from hunger. On his way, Isaiah saw many dead bodies. Liberians have not yet fully assimilated the shadows of the past with the new haunting reality.

Jamal said it will also take time for society to come to terms with the events that happened during Ebola.

“I have a friend,“ he said. “Somebody died from his house to the Ebola. So because of that, I stay away from him when I see him in the street. I stay far up. I wave to him, you know, just like that. I no longer go around him. And it’s kind of heartbreaking, you know, when you see your friend and you don’t go around him. You don’t shake his hand. You don’t hug him. It’s really heartbreaking.”

He added: “After the Ebola, people have to sit and reconcile.“