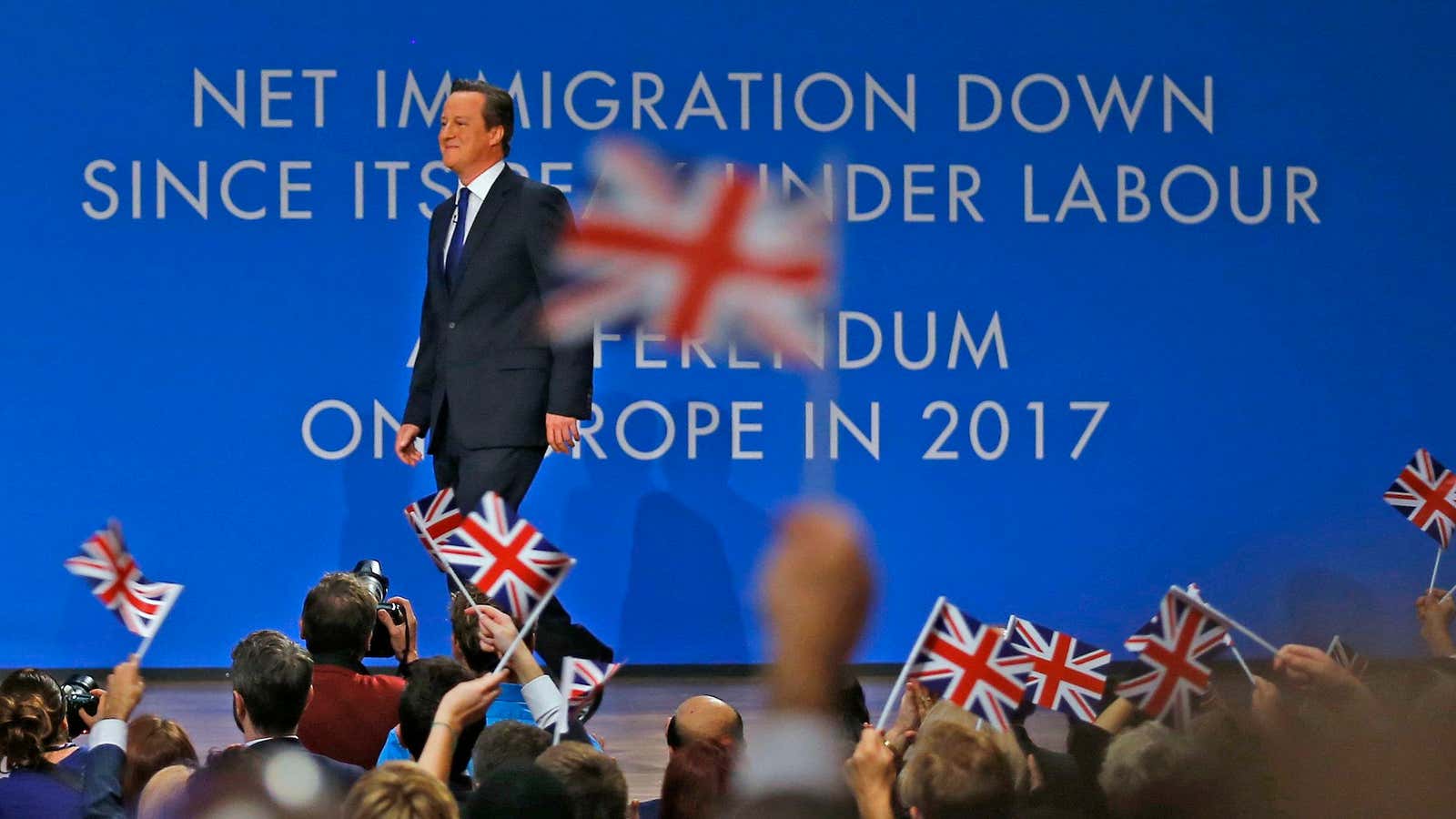

In January 2013, British prime minister David Cameron announced that, should his Conservative Party win the next election, he would renegotiate the terms of the UK’s four-decade-long membership in the European Union and hold a simple in-or-out referendum on whether it should remain part of the EU. With the next election now approaching in May 2015, Cameron promised he would have “one last go” at getting a better deal for the UK in Europe. He sounded weary, considering he hasn’t actually started trying yet.

What do the Conservatives want a new relationship with Europe to look like? Downing Street is reportedly considering an annual cap on European migrants coming to the UK, giving them a national ID number temporarily (paywall) that would prevent them from claiming welfare and tax credits. Another possible move is to repeal a piece of legislation that incorporates the European Convention of Human Rights and replace it with a patriotic-sounding and morally-dubious British Bill of Rights that would make it easier to keep outsiders out. If this is turning into a divorce, it has been protracted and acrimonious—and all about visitation rights.

Europe is still struggling with a moribund economy and the after-effects of a sovereign debt crisis that has left 25 million people across the bloc out of work. The last thing the EU wants to do is spend time debating special treatment for its third-biggest member. This past weekend brought a rebuke from Jose Manuel Barroso, who as the outgoing president of the European Commission doesn’t have to bite his tongue any longer and went all the way to London to make himself heard. “Britain is stronger in the European Union,” Barroso told the BBC. “What would be the influence of a prime minister of Britain if it was not part of the European Union? His influence would be zero.” (Cameron won’t get along much better with Barroso’s successor; Britain tried to block Jean-Claude Juncker’s appointment and failed miserably.)

The reason for all this talk of raising the drawbridge is the ascent of a once-obscure party called the UK Independence Party (UKIP). The party’s message is relatively simple: The UK should get out of Europe. And people have been responding to it. In 2009, UKIP won 16.5% of the vote in European Parliament elections. In May this year, it won more than 27% and became the first party in 100 years that was not the Tories or Labour to win a nationwide election. UKIP recently got its first member of parliament when a Conservative defected and won a by-election—but more tellingly, UKIP lost another by-election to a leftwing Labour candidate by only a few hundred votes. Its appeal goes beyond the traditional left-right divide. If enough voters flee the two main parties, UKIP could hold the balance of power next May.

Both Labour and the Tories are talking sternly about immigration. But as Barroso noted, free movement of labor is a basic tenet of EU treaties and any change would need the approval of all 28 members—in other words, it is not likely to happen. Especially, he added, as 1.4 million British people live in the rest of the EU as emigrants.