Recent research proves what protestors have been saying all along: harsh austerity measures are bad. What’s more, it’s not just bad for people, but for economies too: for debt-reduction, growth, and the long-term job prospects of young people in particular.

Here’s where austerity really bites.

1. It’s making the debt burden heavier, not lighter.

The main point for any of these austerity plans is to get debt in check. A study released at the end of October from the UK’s National Institute of Economic and Social Research finds that when it comes to lowering debt-to-GDP ratios, austerity is self-defeating—particularly the fiscal consolidation programs under way in Europe, and especially when done across many neighboring countries at the same time. The measures dampen growth, which makes the debt-to-GDP ratio higher, at least in the short-term.

In normal times, fiscal consolidation (i.e., reducing the fiscal deficit) does lead to a drop in debt-GDP ratios. But these aren’t normal times. In normal times officials would also be relaxing monetary policy, but interest rates are already exceptionally low, and the European Central Bank (ECB) has been reluctant to adopt less conventional measures like the Fed’s “quantitative easing”. (PIMCO economists argue that it should, showing why the ECB’s monetary policy is actually much tighter than it claims.)

In addition, unemployment is high, while job security is low. This means households and companies don’t have much cash. So even if monetary easing made more money available, it might not spur increased purchasing. Austerity therefore bites harder, quicker.

Meanwhile, European countries are all cutting back at the same time. This means that when austerity measures reduce their national output, it not only hits domestic growth but spills over to neighbors, through reduced international trade.

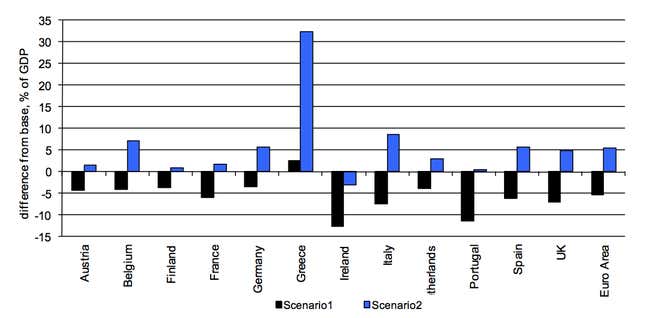

Taking all of these factors into account, the researchers modeled this graph to show the impact of “fiscal consolidation” (including measures enacted or announced between 2011-2013) on debt-to-GDP ratios. The chart below shows both what would happen under normal circumstances (the black bars) and what is happening now (the blue ones).

2. It’s hurting growth.

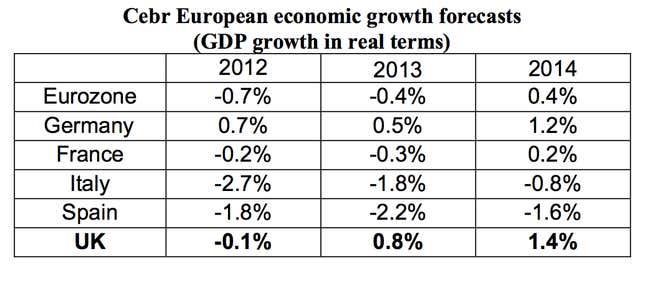

A report earlier this month from the Centre for Economics and Business Research in London forecasts a prolonged recession for the euro zone (pdf) through 2013, with only marginal growth in 2014. The new figures took into account the government austerity measures, though not major surprises like a country dropping out of the euro.

The results: sluggish growth, and possibly worse. “The economic situation in some parts of Europe is moving from bad to catastrophic,” said Douglas McWilliams, the UK think-tank’s chief executive and the report’s co-author. “There is a danger that the economic problems will spill over into social breakdown in many areas of Europe as unemployment soars and governments run out of money.” Here’s a snapshot of their GDP growth estimates for various countries:

3. It leads to a loss of jobs and more.

Government cutbacks lead to job loss in the public and private sectors. This much is obvious. What’s less well known are the long-term effects, especially on young people, of being out of work for prolonged periods of time.

Some numbers first: more than 23% of people under 25 in the euro zone are unemployed. In countries like Greece and Spain, more than half of its young people are without work. In 2011, only 34% of young people across Europe were employed. This is the lowest figure ever recorded by Eurostat.

A study last month from the European Union’s European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions analyzed the economic and social costs (pdf) of having such a large percentage of young people not working. The study looked at the NEET rate. NEET stands for “Not in Employment, Education or Training,” and its something policymakers increasingly care about.

It’s bad enough that young people can’t find work, because someone has to support Europe’s aging population. What’s worse is that a lot of them are increasingly failing to learn new skills. The study found that along with skyrocketing joblessness among young people, a growing proportion of them are not in education or training. As Quartz reported recently, the high unemployment in Greece and especially in Spain is in large part structural, meaning that a lot of the workforce needs to be retrained before they can find jobs.

The study puts the economic cost of Europe’s unemployed youth in 2011 at €153 billion ($195 billion), explaining that it’s a conservative estimate that corresponds to 1.2% of GDP. The bigger costs, however, are societal ones. The so-called NEETS will later have a harder time finding jobs, run a greater risk of suffering from alienation and general dissatisfaction, and are more likely to be the ones you see throwing bottles at anti-austerity rallies.