Google’s recent Search Box feature is but one example of the internet giant’s propensity to use weird ideas to inflict damage upon itself. This sheds light on two serious dangers for Google: Its growing disconnection from the real world and its communication shortcomings.

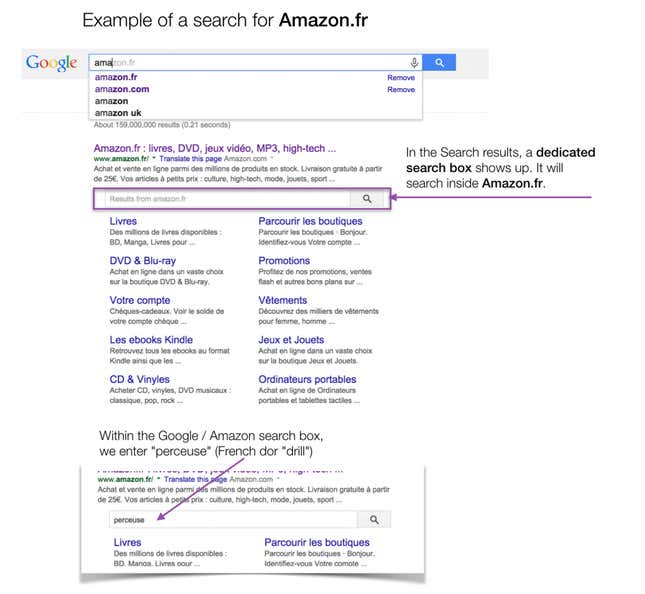

At first, the improved Google search box discreetly introduced on September 5 sounded like a terrific idea: you enter the name of a retailer—say Target or Amazon—and, within Google’s search result page, shows up another, dedicated search box in which you can search inside the retailer inventory. Weirdly enough, this new feature was not mentioned in a press release, but just in a casual Google Webmaster Central Blog post aimed at the tech in-crowd.

Evidently, it was also supposed to be a serious commercial enhancer for the search engine. Here is what it looked like as recently as yesterday:

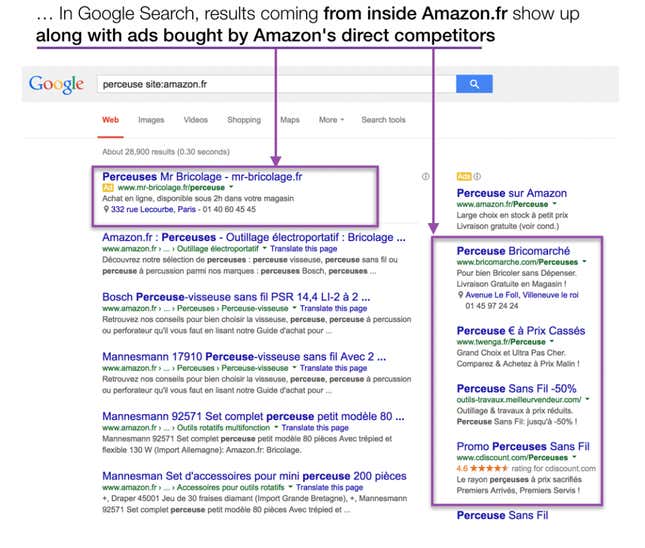

Google wins on both ends: it keeps users on its own site (a good way to bypass the Amazon gravity field) while cashing in on ad modules purchased, in this case, both by Amazon.fr itself bidding for the keyword “perceuse” (drill) on Google.fr, and also by Amazon’s competitors offering the same appliance (and whose bids were lower.)

To be fair, the Google Webmaster Blog explains how to bypass the second stage and how to make a search that lands directly to the site, Amazon.fr in our example. Many US e-commerce sites did so. Why Amazon didn’t is still unclear.

Needless to say, this new feature triggered outrage from many e-commerce sites, especially in Europe. (I captured these screenshots on Google.fr because no ads showed up for US retailers, most likely because I’m browsing from Paris).

For Google’s opponents, it was welcome ammunition. Immediately, the Open Internet Project announced a press conference (last Thursday Oct. 23), inviting journalists seen as supportive of its cause. In a previous Monday Note (see “Google and the European media: Back to the Ice Age“), I told the story of this advocacy group, mostly controlled by the German publishing giant Axel Springer AG, and the French media group Lagardère Active.

Realizing its mistake, Google quickly pulled back, removing the search box on several retailers’ sites, and announcing (though unofficially) that it was working on an opt-out system.

This incident is the perfect illustration of two major Google liabilities:

1) Google’s disconnect from the outside world keeps growing. More than ever, it looks like an insulated community, nurturing its own vision of the digital world, with less and less concern for its users who also happen to be its customers. It looks like Google lives in its own space-time (which is not completely a figure of speech since the company maintains its own set of atomic clocks to synchronize its data centers across the world independently from official time sources).

You can actually feel it when hanging around its vast campus, where large luxury buses coming from San Francisco pour out scores of young people, mostly male (70%) mostly white (61%), produced by the same set of top universities (in order: Stanford, UC Berkeley, Carnegie Mellon, MIT, UCLA…) They are pampered, with free food, on location dental care, etc. They see the world through the mirrored glass of their offices, their computer screens and the reams of data that constitute their daily reality.

Google is a brainy but also messy company where the left hemisphere ignores what the other one does. Since the right one (the engineers) is particularly creative and productive, the left brain suffers a lot. In this recent case, a group of techies working at the huge search division (several thousand people) came up with this idea of an improved search box. Higher up, near the top, someone green-lighted the idea that went live early September. Many people from the left hemisphere—communication, legal, public affairs—might have been kept in the dark, not even willfully, by the engineering team, but simply by natural cockiness (or naiveté.) However, I also suspect the business side of the company was in the loop.

2) Google has a chronic communication problem. The digital ecosystem is known for quickly testing and learning (as opposed to legacy media that are more into staying and sinking.) In practical terms, they fire first and reflect afterwards. And sometimes retract. In the search box incident, the right attitude would have been to put up a communiqué saying basically, “Our genuine priority was to improve the user experience [the mandatory BS], but we found out that many e-retailers strongly disliked this new feature. As a result, we took the following steps, blablabla.” Instead, Google did nothing of the sort, only getting its engineering staff to quietly remove the offending search box.

There is a pattern to Google’s inability to properly communicate. You almost discover by accident that these people are doing stunning things in many fields. When the company is questioned, it almost never responds by providing solid data to make its point—that’s simply unbelievable from a company that is so obsessed with its reliance to hard facts. Recall Google’s internal adoption of W. Edwards Deming’s motto: In God we trust, all others bring data.

In parallel, the company practices access journalism, picking the writer of its choosing, giving him/her a heads-up for a specific subject hoping for a good story. Here are two examples from Wired and The Atlantic.

These long-read “exclusive” and timely features were reported respectively on location from New Zealand and Australia. They are actually great and balanced pieces since both Wired’s Steven Levy and The Atlantic’s Alex Madrigal are fine journalists.

While it never misses an opportunity to mention its vulnerability, Google is better than anyone else at nurturing it. Like Mikhail Gorbachev used to say about the crumbling USSR: “The steering is not connected to the wheels.” We all know what happened.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.