This post has been corrected.

Editor’s note: Mustafa Nayem is a 33-year-old Afghan-born Ukrainian and one of the country’s most popular bloggers and journalists. A Facebook post he published on November 21, 2013, is credited with kicking off the protests in the Maidan, the central square of the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, that led to the ousting of president Viktor Yanukovych three months later. The party loyal to the new president, Petro Poroshenko, gave Nayem a spot high up on its list, guaranteeing his election to the Rada in the parliamentary election held yesterday (Oct. 26).

With his seat more or less assured, Nayem and two other journalists-turned-politicians, Sergey Leschenko and Svitlana Zalishchuk, decided to investigate allegations of vote-buying in an electoral district in central Ukraine. (Some seats in the Rada are filled by district voting, and some, like Nayem’s, from party lists.) Photographer Misha Friedman tagged along for what proved to be a rather more eventful election weekend than any of them had anticipated.—Gideon Lichfield

On the morning of Oct. 25, Nayem sleeps on a train from Kyiv to the town of Znamyanka, part of electoral district 102. The previous day, he had traveled 500 miles speaking to students around the country.

Nayem arrives in Znamyanka.

Strategizing with a group of election observers. Dissatisfied with the hand-drawn district maps, Nayem created a Google map marked with the locations of the most contested polling stations that he shared with the more technologically savvy members of his team, so they could concentrate their efforts there. Their strategy was to record any violations they saw and report them to the police.

A local woman shows how someone on an electoral committee might distort the vote count without other committee members noticing, by hiding a cut-off piece of a pen’s ink cartridge in her hand and using it to spoil ballots marked for a particular candidate. Nayem records the demo with his phone; he then uploads it to his Facebook page.

Nayem and his team meet with representatives from the US National Democratic Institute. (Correction: We previously identified it erroneously as the National Endowment for Democracy.) His visit to the region has generated a fair amount of foreign interest.

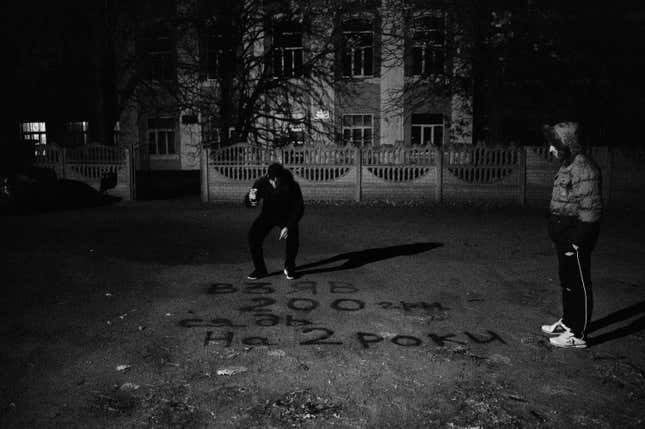

There were reports that people were being offered 200 hryvnias (about $15) to vote for a particular candidate, Oles Dovgii. Dovgii, in turn, claimed such payments were a “provocation” created by opponents trying to discredit him (link in Russian). Here, local activists spray “Take 200 hryvnias, sit [in prison] for two years” on the ground near a polling station on the night before election day.

At 6am on Oct. 26, Nayem blogs before going out to monitor the voting.

Looking at lists of candidates outside a polling station.

The second polling station Nayem and his team visit is at a small village, Kazarnya, where 200 people are registered to vote. Friedman relates: “When we arrived it was still early in the morning. We saw a bus with a large group for such a small station, 30-40 people waiting to enter, which was quite unusual. Even so, we might not have noticed anything strange—it’s not like anyone was standing around with 200-hryvnia notes. But then Mustafa saw a woman rushing out of one room and into another with a folder. He followed her and asked her to show it to him. It was a whole bunch of official documents, and on top of them was a handwritten list of names with numbers next to them. She closed the folder and a discussion began. By then we’d all entered the room. She tried to rip the list into shreds. We got some pieces, she got some pieces, and it became a circus.” Here Nayem talks to the woman, Lyubov’ Nikolaevna.

Nayem calls the police while Nikolaevna remonstrates with him and other people record the exchange.

Friedman: “Her husband walked in, and then the story changed every 15 minutes. First she became scared, then she got angry. They went through the full range of emotions.”

A local policeman arrives in response to Nayem’s call.

A homeless man tells Nayem he was paid 200 hryvnias to vote.

Nayem is a high-profile figure, and the local police chief soon arrives.

Thanks to Nayem’s social-media posts, the event is now a big story; local TV crews arrive and interview Nikolaevna.

Having filed their police reports, the team leaves Kazarnya and is on the way to another village when seven men attack their minibus with rocks. They manage to smash some windows and the sunroof; one person is lightly injured. “I didn’t get any pictures of the attackers,” says Friedman. “I was on the floor of the bus covering my head.”

Instead, he uses the shattered windows to take a selfie afterwards.

The group manages to get away from the attackers, and Nayem posts pictures of the damaged bus to Facebook. Later, they return to take more pictures of the scene of the attack.

Svitlana Zalishchuk and Sergey Leschenko, who were elected to the Rada along with Nayem, after the attack.

At 11pm, the crew waits at police headquarters to give additional statements, keeping themselves occupied listening to the first exit polls.

Nayem and his crew then go to the district electoral commission, where the electoral committees of the various towns and villages show up to deliver their ballot boxes.

At around 12:30am, the committee from Kazarnya shows up. “They saw us and got nervous,” Friedman says.

“They realized some kind of official stamp was missing from the paperwork. They didn’t even get as far as counting the ballots.” They decide not to file their electoral report.

1:30am: the Kazarnya electoral committee takes its ballots back to the village.

2am: Nayem’s crew hold a final strategy meeting. They’ve been up for 20 hours.

Follow Misha on Twitter @mishafriendman.