China’s polluted air kills at least a million people a year—and is becoming enough of a source of public outrage that it threatens Communist Party’s legitimacy. But while the government’s bid to clean up the air has focused mainly on cars and factories, there’s a huge source of harmful emissions it’s overlooking: shipping.

Thanks to lousy regulation, a medium-sized container ship can spew as much PM2.5—fine particles that are particularly harmful to humans—or the equivalent of half a million new trucks in a single day, the Natural Defense Resources Council (NRDC) argues in a report published today.

“Along with the massive cargo every ship and truck delivers to these ports, comes even more air pollution in the form of a toxic stew of cancer-causing diesel exhaust and black carbon that chronically plague China’s growing port regions,” says Barbara Finamore, NRDC’s Asia director.

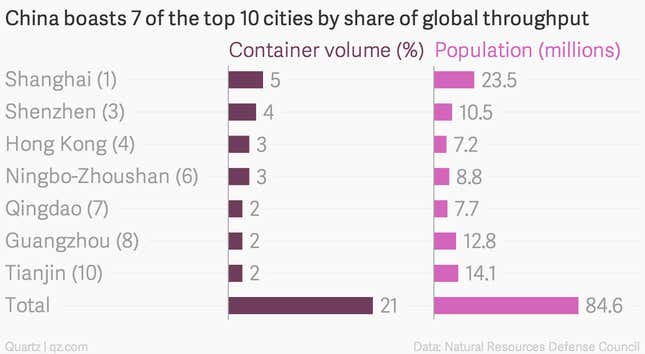

Just four decades ago, China had no large container ports; international trade flowed through Hong Kong, then under British rule. Now China handles around 30% of global container volume, boasting seven out of 10 of the world’s busiest ports. Booming trade has helped make these huge commercial hubs—and, not surprisingly, population centers. More than 77 million people live in mainland China’s six leading port. If you count Hong Kong, that totals more people than live in Germany.

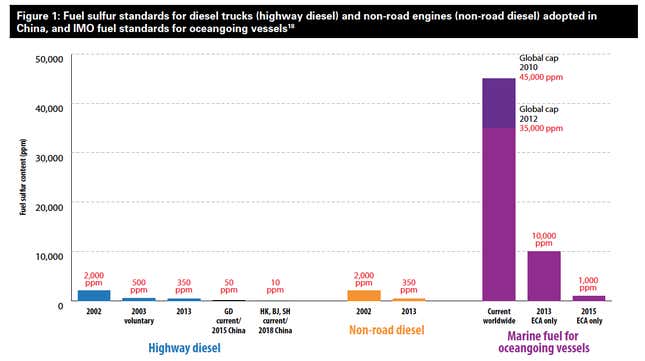

The Chinese government allows those same ships to use cheap oil called “bunker fuel,” which, since it’s packed with sulfur, converts into harmful particles when burned.

There’s a reason ships like to use it, though: a tonne of bunker fuel is around $290 cheaper than a low-sulfur fuel, according to NRDC. However, strict regulations outside Asia mean cargo vessels switch to low-sulfur fuel to dock in North American or EU ports. Here’s how emissions from bunker fuel compares with diesel-burning vehicles, on a per-unit-of-of-energy basis:

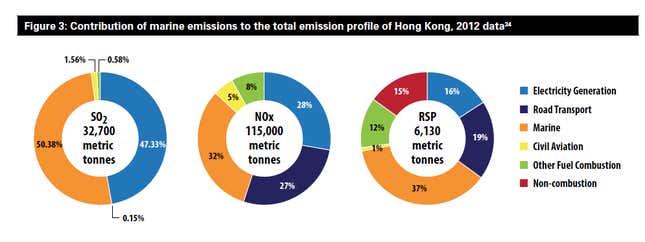

It’s hard to isolate exactly what the impact is. However, a 2008 study covering Hong Kong and the Pearl River Delta found that emissions from both ocean-going and inland ships in the PRD led to more than 1,600 premature deaths in the mainland, and at least 1,200 in Hong Kong.

And marine emissions don’t just harm humans; they also warp ecosystems and contribute to global warming, including by generating what’s called “black carbon,” meaning sooty emissions that absorb atmospheric heat. Though shipping is the most fuel-efficient form of cargo transport, nine-tenths of the world’s goods travel by sea, according to a recent paper by Carbon War Room, a non-profit research group focused on commercial low-carbon technology. The industry emits more than 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year, making it the sixth-larges emitter of greenhouse gases globally.

Yet “regulation of air emissions from ships is virtually nonexistent today in China,” says the report. That could start to change soon. Hong Kong plans to be the first in China to require vessels to use low sulfur marine diesel in its ports. Shenzhen also recently announced a slew of port cleanup initiatives.