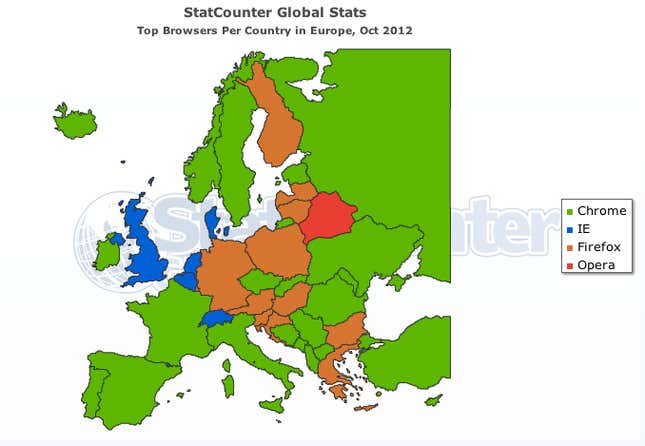

Opera lives on in Belarus. Not the musical drama, but the world’s fifth most popular web browser.

StatCounter, which uses data on browser usage across some 3 million websites, identifies Belarus as the only country in the world where Opera—which elsewhere is something of a niche product—commands the largest share of users:

Why is the former Soviet republic a shining ruby of web browsing rarity? Socialism!

First, some history. Opera is the second-oldest active browser in the world; when it was released by Norwegian techies in 1996, it filled a role the way that Firefox and Chrome would later. Offering new features the stodgy leaders didn’t have and options that web geeks preferred, Opera was real competition for Microsoft’s Internet Explorer juggernaut and the web-browser creators behind Netscape.

The browser wars were vicious and popular features were quickly commodified. The business became more about reach. Internet Explorer dominated computers running Windows, with which it was bundled, as Safari did for Apple users. Chrome has benefited from its integration with Google, as more and more people use the search giant’s email, document-storage and other apps. Firefox, being open-source, built up a following of people who liked its independence and its vast array of community-built add-ons.

By contrast, all the Norwegian company behind Opera can offer is the best feature set it can craft and the fastest browser it can make. But that turned out to be the best strategy in Belarus, which remains a largely socialist state with the infrastructure to match, including a state-run communications monopoly, Beltelcom. ”One of the main reasons why Opera has a large market share in Belarus is because of the Internet infrastructure in the country; it was pretty bad a few years ago,” Espen André Øverdahl, one of Opera’s community managers wrote in an email, pointing to features that allow users to strip out images and other bandwidth-gobbling web extras.

I got in touch with Gleb Kanunnikau, a web developer and designer who lives in Minsk, and he seconded Øverdahl’s assessment. ”The state telco basically sets the floor on internet access cost across the country… so people save money by using [Opera],” Kanunnikau wrote. “This has been important historically since the first ADSL plans without monthly traffic limits started appearing only around 2009-2010—and they were limited in speed.”

It’s not just the desktop version, either. Anyone wanting to use mobile internet in Belarus before 2010 had to use Opera Mini, which was designed for phones that couldn’t support a regular web browser, because the first Android phones weren’t imported until that year and iPhones weren’t allowed until last year. “Opera Mini allowed anyone with a dumb phone to get online and to browse the web almost for free,” Kanunnikau writes. “Its advanced traffic compression algorithms mean that even today people are still using it on our slow and expensive mobile connections —even on Android devices and iPhones.”

In short, Belarus’s socialist regime made a browser that prized efficiency extra valuable. And although its competitors (especially Chrome) have now largely caught up, it also can’t have hurt that Opera was an early leader in security features like encryption, useful in a police state.

Opera has attempted to build on this success, encouraging its community in Belarus. Øverdahl’s job includes a lot of social media outreach, and Kanunnikau (whom I reached independently of Opera) reports that the company has organized education events about the latest developments in web design and coding in Belarus, and even provided him and a friend with a small grant to organize a barcamp, a kind of user-generated tech conference.

The company should hope its roots in the country are deep, however, because the cost of internet access appear to be dropping—thanks again to the economic mismanagement of Belarus’s dictator-president, Alexander Lukashenko. Shortly before his reelection in 2010, Lukashenko’s government raised state wages by the equivalent of $500 a month in a bid for popularity. This spurred inflation and led many in Belarus to convert their rubles into dollars or euros, prompting a monetary crisis. In 2011, inflation hit a peak of 109%; the country instituted capital controls, allowed its currency to float and required a $3 billion bailout. The ruble would eventually devalue some 189% against the dollar.

“Ironically, the devaluation helped to bring the prices down, it was the one good effect of the economic meltdown that we went through in 2011!” Kanunnikau writes. “Beltelecom prices didn’t go up despite the devaluation to reduce the inflationary pressure on the economy to some extent—but their profit margins were very high to begin with.”

For example, Kanunnikau notes that in 2009 a 1 Mbps internet connection cost 129,500 rubles, then $45, and the median monthly salary was about $342. Today, a similar plan costs 59,400 rubles, about $7, and the median monthly salary has grown to $470. If that trend continues, the advantage for super-efficient web browsers like Opera may diminish. But it has a good head start.