Thank you for your email. But I’d like you to remove me from your mailing list. Permanently.

I know this sounds harsh. Please bear with me. I’ll try to explain why.

The system is not your fault.

In the days before email, press releases cost money to send. There were still too many, but they were limited, and easy to sort from the magazines, research reports, and indignant readers’ letters.

Now, however, spamming as many journalists as you have email addresses for is practically cost-free.

Ouch, I said it. Spamming.

I know that’s an ugly word. I know your interview opportunities and funding rounds and product launches are not breast enlargements or pharmaceutical offers or Nigerian money transfer schemes. Nonetheless, they are unsolicited approaches, in very large quantities, of things I am very, very unlikely to want. That, give or take a fraud or two, is spam.

You are the victim as much as I am.

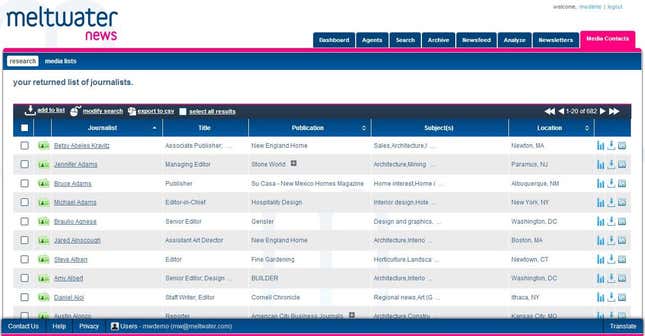

“Now hold on,” you protest. “This is not cost-free. I pay for that media database.”

Oh, I know you do. And you’re being fleeced. Here’s why.

First, no news outlet gets stories from mass-emailed pitches. No news outlet you or client would actually care about, anyway. (Admit it: Most of the places you include on that “media coverage” list you draw up make you die a little inside.) Because if I know hundreds of other journalists are getting the same story, why would I bother?

Second, whatever we told Gorkana or Cision or Meltwater our “beats” are, you can treat that information as garbage, because for your purposes, it might as well be.

We’re quirky people, journalists. Scratch that: We’re people. We have obsessions, blind spots, perspectives, framings. I like to cook and you like to cook, but I’m a carbon-conscious flexi-vegetarian and you basically don’t care as long as it didn’t have more than eight legs. He covers architecture and she covers architecture, but one of them is obsessed with green office buildings and the other won’t even look at it unless it has a wood frame, a cute family, and preferably a fascinating but terrible story about insect infestation.

You are laboring under an illusion.

I have never worked in PR, but it’s clear that it lends itself to two natural strategies. The first involves getting to really know journalists: not just what they cover but what they’ve written before, what they’re experts in, where they’ve lived, the things they believe in, the things they love, the things that make them mad. It also means understanding the nuances of their news outlet — who it writes for, how it frames its stories (people or issues? gossipy or wonky? newsy or off-newsy?), how its readers find those stories. (A website that relies almost entirely on social media is liable to do stories quite differently from one that gets a large chunk of readers through its homepage.)

This, of course, is extremely time-consuming. You probably call it “high-touch.” Or maybe slow PR.

The other natural strategy is what you’re doing now. I don’t know what you call it. I call it failure.

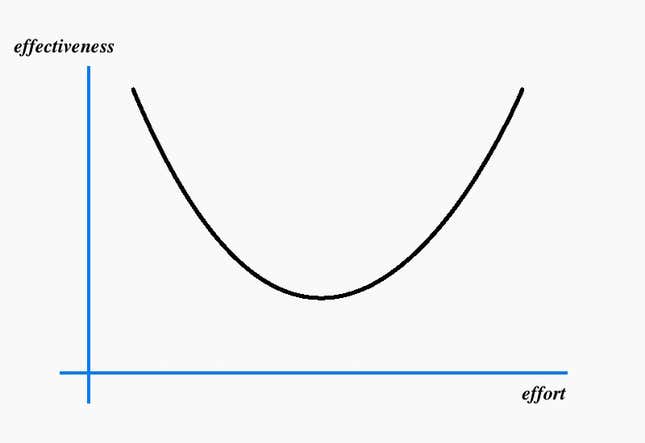

I suspect you know this strategy is sub-optimal, but you pursue it because you believe implicitly in a curve like this:

High-touch—the right side of the curve—yields results. But it’s hard work. Mass-mailing lots of people—the left side—means 99% of them don’t even read your email. But you assume that, in aggregate, it works out about the same.

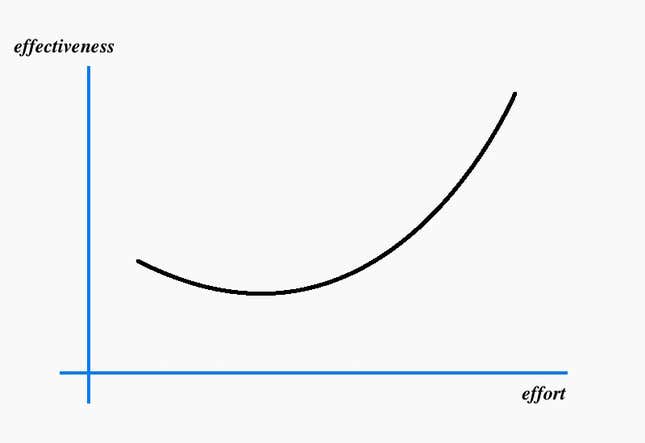

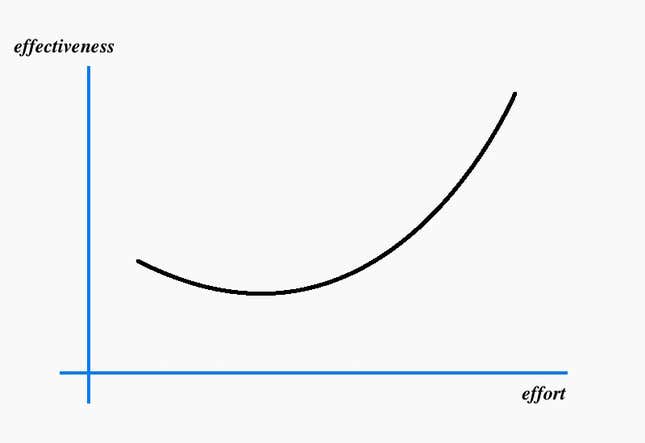

I’m here to tell you that, in my view, the curve looks more like this:

It looks like this because the more emails like yours I receive, the less likely I am to look at any of them. Yours might be the one in a hundred that contains the germ of a story I would actually want to do. But I’m not going to read through and figure out what that germ is. I don’t have the time.

And besides, that should be your job.

And it’s costing you dear.

If there were a special spam filter for PR emails, I would use it. I would pay for it.

Since there isn’t such a filter, here’s what I do when I get one of your emails.

(Warning: You may not like this.)

First, if you have one of those email addresses that ends in ****pr.com, I’m afraid you’re already toast. My filters auto-delete those.

If not, I look for the “unsubscribe” link at the bottom, and click it.

If there is no unsubscribe link (Why not? Where are you, the 20th century?), I send a canned response. “Thank you for your email, but I’m afraid this material isn’t of interest. Please could you remove me from your mailing list?” If I get another email from you, I’ll send that response again.

If that fails, I’ll add your address to my auto-delete. Even if you subsequently come up with the absolutely perfect, tailor-made pitch, or want to tell me how wonderful/witty/ludicrously ill-informed/potentially libelous my last article about your client/step-sister/dog/favorite political candidate was, I will never see it.

So here’s what you can do.

Let’s look at that curve again.

You can stay there, on the left. It’s nice and comfy there. You’ll get a little lift. Maybe enough to convince your clients that you’re doing something productive. Maybe even convince yourself. For a bit.

Or you can be on the right. You really want me to write about this? Then think about how I—me, specifically, this journalist, this individual person—would write it. Why would I care? Why would my readers care? How does it fit with what I’ve done before? How does it fit with my publication’s mission? How would I make it different and original? What makes it more broadly relevant? What makes it timely and important? What sort of email you could send that I would actually read? (It isn’t that hard to learn. There are courses.)

And yes, the chances are better than even that I’ll still say no. And yes, each rejection will be painful. But you’ll learn from each one. And the next time you’ll get better.

Because look at it this way: Right now, you’re getting rejected hundreds of times a day. It’s just that your software hides the pain. And you’re not learning, or getting better.

Best wishes

A. Journalist