Contrary to the adage, there actually aren’t plenty of fish in the sea—at least, not the commercial kind. This is thanks in part to rampant undocumented, unreported, and otherwise illegal fishing—which by some estimates, costs the global economy $23 billion a year.

But never fear, Google is here.

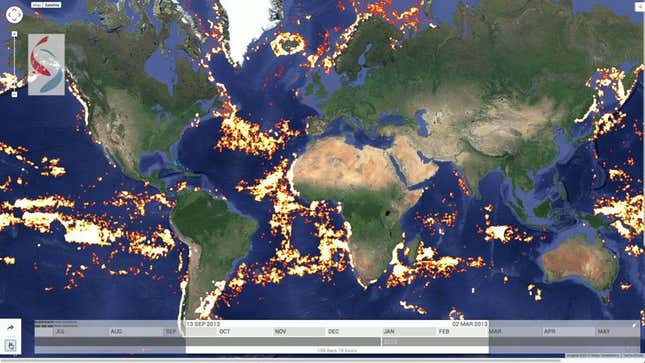

In partnership with nonprofit groups Oceana and SkyTruth, the web giant just rolled out Global Fishing Watch, a website that reveals the positions of thousands of fishing boats in near real-time.

In addition to being cool-looking, Global Fishing Watch allows authorities to monitor shady activity much more effectively than they can with radar screens and binoculars. By aggregating and analyzing GPS broadcasts of a ship’s location, Global Fishing Watch can determine a vessel’s identity, speed and direction. Here’s a country breakdown:

Most of those vessels in the map above aren’t doing anything suspicious. The problem, though, is that those that are fishing illicitly often do so unnoticed.

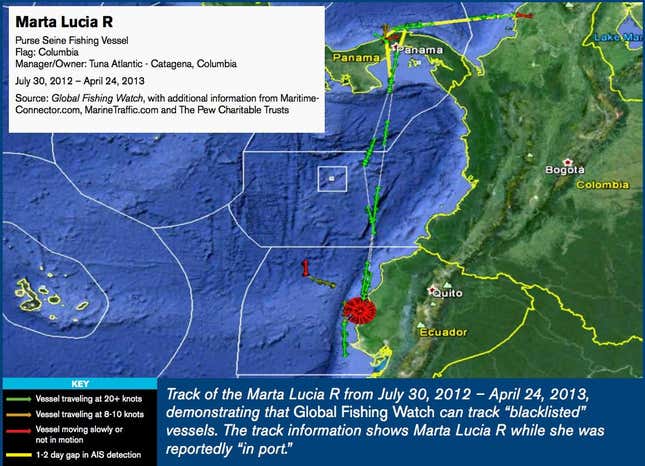

Take for instance, the Marta Lucia, a Colombian tuna-fishing vessel that the Inter-American tuna regulator blacklisted in 2006 because it was catching tuna during the off-season. Undeterred, the Marta Lucia continued catching tuna. Since then, the US, EU, and the Atlantic tuna regulator have also documented its illegal activity.

In Jun. 2013, the Colombian government successfully lobbied the Inter-American tuna regulator to remove Marta Lucia from its blacklist, declaring that the vessel had been in port and hadn’t operated since Jul. 2012 (pdf, p.80).

If the tuna regulator had access to Global Fishing Watch, it might have reached a different verdict.

As Oceana reports (pdf, p.12-3), the site’s tracking shows that the Marta Lucia was most definitely not docked in Cartagena, as the Colombian government stated. Instead it was lingering in Ecuadorian waters off Manta, where it stayed until Apr 2013:

This is hardly unusual. The sea is so vast that it’s hard for both regulators and countries’ coast guards—especially those of poor countries—to police them thoroughly. That makes it easy for boats to cast nets and longlines in areas where fishing is forbidden, or in territorial waters reserved exclusively for vessels from that country. Corruption also means authorities look the other way.

There are many reasons illegal fishing is such a destructive practice. Fishing in protected areas threatens fragile ecosystems. It’s also terrible for legal fishermen. As of 2011, 29% of fishing stocks were overfished (pdf, p.37)—being caught at a rate faster than they can replace themselves—while another 61% were “fully exploited,” says the United Nations—fished to the brink of being unsustainable.

This leaves the global fishing industry—which employes hundreds of millions of people, and feeds still more—teetering in a precarious state. Scientists calculate how many fish the industry can legally catch before collapsing a given stock. Illegal fishing pushes that fish population much closer to collapse than those calculations account for.

The featured image is by Flickr user ollie harridge (the image has been cropped).