These are happy days for the once-downtrodden airline industry: Profits are high and costs are low, particularly the price of oil, which is the industry’s biggest expense. But that’s no consolation to flyers.

Despite assurances from the industry that cost savings are on the way, the average airline ticket is getting more expensive, due in no small part to fuel surcharges that can cost more than the actual flights.

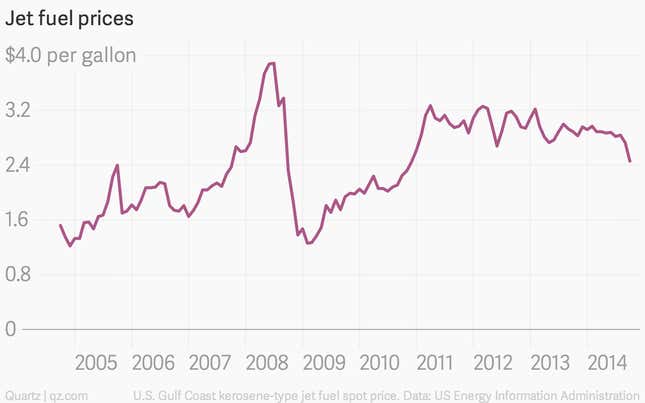

One-way domestic US coach fares are up 1.7% in the year to September, according to Bloomberg. Jet fuel prices have fallen by about 15% over the same period.

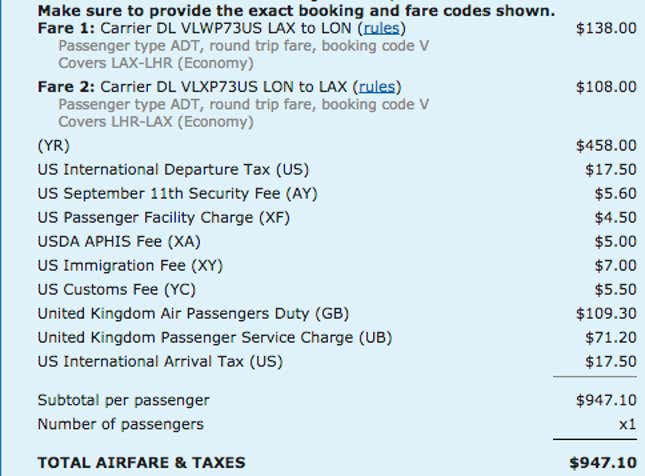

Here’s a round-trip flight on Delta from Los Angeles to London (Dec. 5-12), with a fuel surcharge of $458, nearly half of the $947.10 total fare. The data comes from Google’s ITA software; fuel surcharges are coded as “YR.”

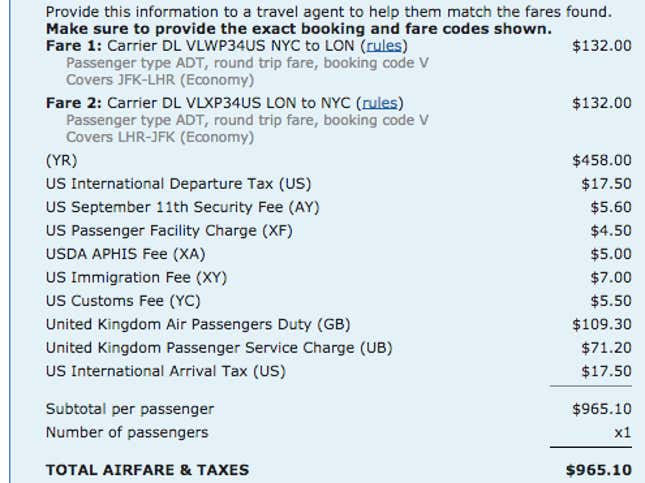

A similar trip from New York to London, which would presumably burn less fuel since it’s about 2,000 miles shorter, has the exact same fuel surcharge:

What’s going on here? The short answer is that fuel surcharges, introduced by many airlines in the early 2000s as the price of oil was on the rise, don’t bear much relation to how much fuel actually costs. Put another way, they are arbitrary numbers that the industry adjusts to maximize their profits while staying competitive with other carriers. After all, fuel is an inherent part of any airline’s operations: It might as well charge you a “surcharge” for the costs of the captain and flight attendants.

The made-up nature of the fuel surcharge is reflected by the way it is applied—different customers may pay different fees depending on what class they’re traveling in or seemingly arbitrary combinations of connections. Most travelers will never even see the fuel surcharge unless they use a ninja-level airline booking tool like Google’s ITA Software.

So why use fuel surcharges at all? Aside from inertia, there is one very good reason: Under many frequent-flyer plans, if you’re using miles to book flights on a partner airline, you still have to pay the associated taxes and fees.

And when will the airlines’ lower costs translate into lower prices for flyers? Don’t hold your breath.

“In a strong demand environment, we don’t plan to go off and just proactively cut fares,” American Airlines president Scott Kirby told investors recently. Lowering fares now, only to hike them again if oil prices rise, “would be absolutely the worst thing that we could do,” said Southwest CEO Gary Kelly.

What’s going on here is that the airline industry—notorious for racking up billions of dollars in losses—has found itself in an ideal situation, albeit one that probably won’t last. Oil prices typically fall only during downturns, causing a drop-off in big-spending business clients, but not this time: Especially in the United States, business is booming at the same time as oil prices are plummeting—a lucrative combination that airlines are eager to cash in on.

As the Associated Press’ Scott Mayerowitz noted yesterday, airlines are also “on the largest jet-buying spree in the history of aviation,” taking advantage of cheap credit to order more than 10,000 fuel-efficient planes—hardly the time to start cutting prices, especially when demand is high. “Simply put,” he wrote, “Airlines have no compelling reason to offer any breaks.”