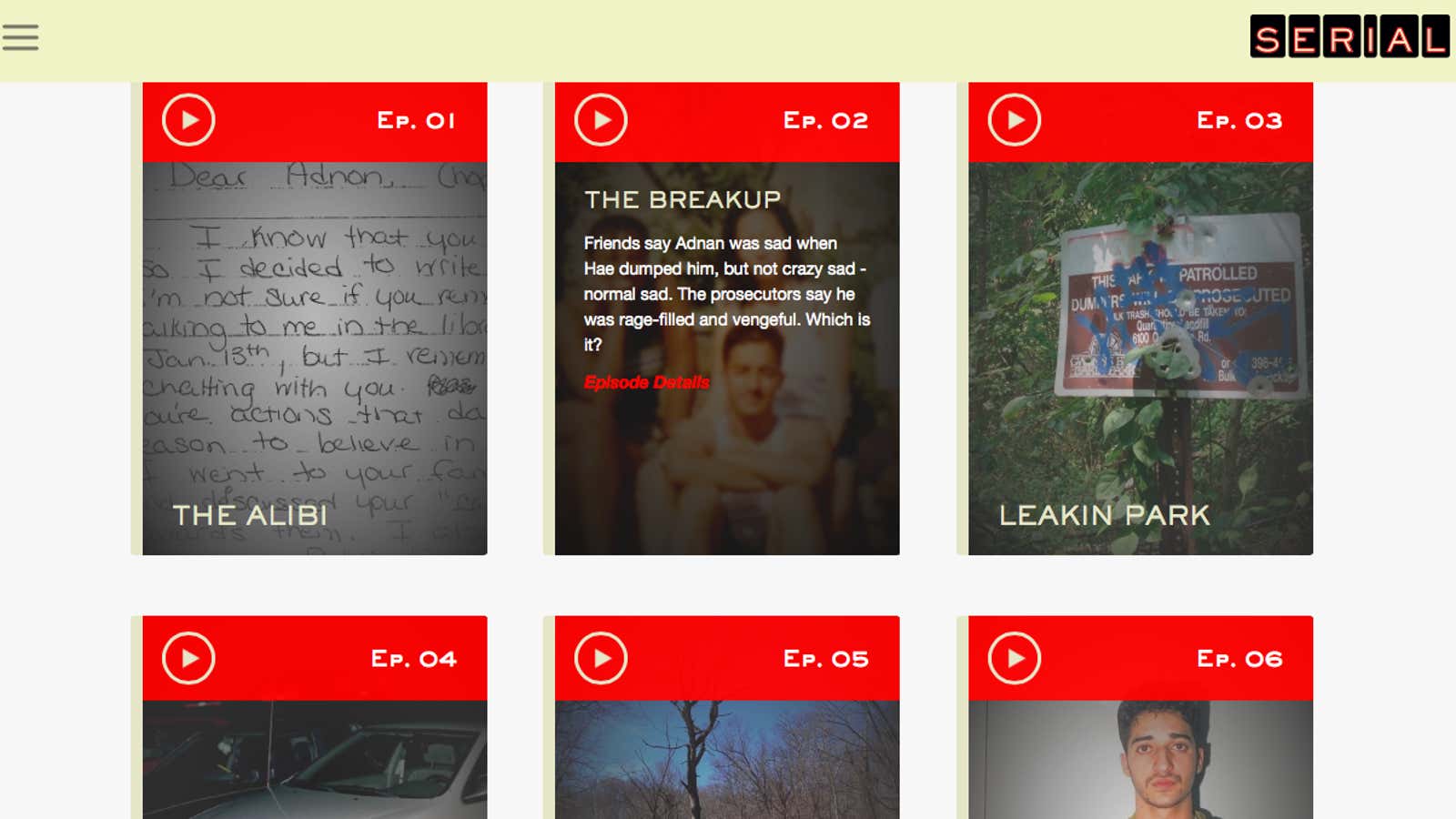

In September of this year, Sarah Koenig, a producer for the venerable public radio anthology show This American Life, pitched an idea to the show’s host and co-creator, Ira Glass, for This American Life’s first-ever spinoff. Like its radio mothership, it would cover a single theme from a number of different angles, essentially illuminating it by diffraction. Unlike This American Life, however, Serial would cover just one story—and instead of compressing this coverage into a single hour, it would play out episodically over months, one chapter per week, delivered via downloadable podcast.

The story Koenig offered up is one that was instantly intriguing: The 15-year-old murder of a young Korean American high school student named Hae Min Lee by her Pakistani American boyfriend Adnan Syed, and the kaleidoscope of varying truths and lies around the case. Since its release in October, the podcast has been a shockingly huge hit—it’s the most-listened to podcast in the world, and the fastest one in history to reach five million streams and downloads. But the podcast’s success has also prompted some Asian American critics to take a closer look at its premise and process, calling Koenig out for the “white privilege” she demonstrates in leaping into a complicated story, set in a world of intersecting communities of color, with little understanding of the cultural contexts, ethnic nuances or racial sensitivities at play.

As Jay Caspian Kang writes in a scathing essay for The Awl, “Koenig is talking about our communities [Kang is himself Korean American], and, in large part, getting it wrong. The accumulation of Koenig’s little judgments throughout the show… should feel familiar to anyone who has spent much of her life around well-intentioned white people who believe that equality and empathy can only be achieved through a full, but ultimately bankrupt, understanding of one another’s cultures.”

That’s one way of looking at Koenig’s enterprise—as pure cultural tourism, exploitative of the people and communities involved for the sake of streaming-audio melodrama. And it’s not an inaccurate one, either: There’s something deeply uncomfortable about how the show treats these people — the Korean American deceased, the Pakistani American convicted killer, the black friend whose testimony led to that conviction, and all of their friends and loved ones—as mere characters, “colorful” in both senses of the word, for the sake of engaging and enthralling millions of listeners each week. Families have been destroyed by this case. A young man has spent over a decade in prison. And there is, still and forever, a dead young woman, who no doubt would have liked to be remembered for more than just her death (and her Sweet Valley High-esque diary).

But as Kang himself writes, there’s a more charitable way to view the podcast—“one in which Koenig has been intentionally presented as a quixotic narrator with Dana, her occasional sidekick on the show, playing the role of Sancho Panza,” he notes, admitting that “There’s ample evidence that this is what’s the show is striving for.”

This, to me, is the core of the show’s appeal, and the reason why I, like millions of other listeners, have become obsessively fascinated with it. Yes, there’s something a little freaky and white-savior-complex-y about “Serial.” But throughout the series, Koenig has very consciously forefronted her ethno-cultural ignorance, the things that compromise her as a reporter and an actor in this drama, in ways that I think very few white journalists choose to do.

And that’s a problem. Because ethnic naivete and cultural clumsiness are hardly unique to Serial. They’re woven into the fabric of its parent show, This American Life, which over its 20-year history has essentially made a cottage industry out of white-privileged cultural tourism. (One need look no further than This American Life’s most epic fail, the taken-at-face-value airing of monologist Mike Daisey’s fabricated investigation of Apple’s outsourced labor practices in China, as evidence.) They’re effectively the default for public radio in general, which has become a veritable winter wonderland after the cancellation of long-running NPR mainstay Tell Me More, hosted by the inimitable Michel Martin.

Indeed, they frankly dog much of “mainstream” journalism in general, which even today suffers from an absurd lack of diversity and—even worse—a residual obsession with the false god of “objectivity,” which celebrates lack of context as an asset as opposed to a gigantic handicap.

Which is why Koenig’s approach actually offers up a valuable lesson for other journalists covering communities to which they do not belong. You may take issue with her sensitivity, or with the effort she makes to immerse herself. What you can’t challenge, however, is the level of transparency she provides regarding her blinkered perspective.

Contrast her befuddled candor with the spectacle we regularly see of television reporters parachuted into erupting hotspots in the Middle East or Africa or Asia—or Ferguson, Missouri—and gravely giving “authoritative” standups, expecting us to accept their instant analysis about the intensely complicated events unfurling around them.

In that light, Koenig’s openness about her cultural ignorance makes her a model by comparison… and not just for white journalists. In listening to the series, I’m finding myself forced to confront a lot of preconceptions and biases I personally have about teenagers of color and about immigrant families and communities—ones that I probably wouldn’t think through as closely if the podcast weren’t being hosted by an oblivious white reporter.

After all, despite being an Asian American, I’m from a different generation, an advantaged socioeconomic class and an elite educational background. I have my own blinders, and am realizing through the show the many things I take for granted even as I cover the community to which I was born.

In short, the mirror of Serial has made me reflect on myself, and to recognize that I, too, have privilege to check. Perhaps it takes a third-person perspective to make us ask these questions. Which is why, for all of its flaws, I’m glad it’s here, I’m listening critically but loyally and I look forward to following it through to its conclusion—however it ultimately ends.