On Thursday, Americans will gather to celebrate Thanksgiving and they will do so at the dinner table. The meal, with roots in the ancient traditions of harvest festivals and in the religious fervor of the Puritans who settled here, has grown into a secular feast of abundance. Whether taking place in Duluth, Minnesota or at the Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan, the American tradition is to roast a turkey and eat it along with a slew of side dishes, all in the company of family and friends. So here’s the thing: while it is an iconic food, no one would argue that a roast turkey is the American national dish – turkey on multigrain for lunch aside. Plopping a turkey on an overladen table is reserved almost solely for this day.

So, we wondered, what other food traditions around the world are universal, sometimes begrudgingly consumed, national, cultural symbols? For example, Koreans gather for songpyeong to honor the fall harvest and Iranians eat sabzi polo va mahi to greet the coming of spring. Oh and the turkey of Turkey? Most likely a dessert called ashure, or “Noah’s Pudding” which is a grain, fruit and nut concoction served on the tenth day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar.

Kräftskiva

A friend who lives in Sweden told me, “In other countries maybe holidays are about getting gifts or getting drunk or family time, but in Sweden it’s really all about food.” Midsommar, or the summer solstice, is a festive time, when Swedes dance, eat, and drink to celebrate the long daylight hours after a dark, cold winter. To celebrate Midsommar, Swedes eat boiled potatoes, pickled herring, cream and dill, and wash it down with schnapps. The Swedes have other seasonal foods as well: Late August is the time for Kräftskiva (a crayfish party), when Swedes boil crayfish in brine and then serve them cold with crown dill. Also served is Västerbottensost Paj, an aged-cheese quiche.

While you won’t find Swedes eating Turkey on Thanksgiving, you will find them eating pea soup and pancakes. Since before the Reformation, Catholic Swedes have eaten a hearty meal on Thursdays to get them through a day of fasting on Friday. Pea soup, or Ärtsoppa, usually has ham or sausage in it, and is served with mustard to be stirred in. Swedish pancakes, thinner than American ones and topped with fruit jam, are served alongside.

Þorramatur

While Swedes worship the sun, Icelanders make the best of the dark days of winter. þorrablót, or Thorrablot, a midwinter holiday from pagan times that falls on the thirteenth week of winter, in late January, is celebrated with a feast known as Þorramatur. The festival honors the Norse god Thor (Þórr) and the Þorramatur meal includes cured meats and fish, a dense, sweet rye bread called rúgbrauð, and an Icelandic aquavit infused with caraway called brennivín. The standout element of any Þorramatur is hákarl, made from fermented Greenland shark that is buried in a hole in the ground for several weeks and then hung to dry for four to five months. In fact, the shark meat cannot be eaten when fresh — it contains poisonously high levels of urea — so the rotting allows uric acid to drain off. Even so, hákarl retains a strong ammonia smell and can be an offputting dish to new eaters.

蛇羹 (Snake soup)

Residents of Hong Kong stay warm in winter with a steaming bowl of snake soup. In traditional Chinese medicine, snake meat is believed to be a “warming” food that heats the body, a property known as “yang” in Chinese to counteract the “yin” of the cold season. The soup contains the shredded meat of at least two snakes; water snakes and pythons are popular choices, but diners can choose among Chinese cobra, branded krait, Indo-Chinese rat snake, or sharp-nosed viper. Many say the snake flesh tastes as innocuous as chicken, but snake soup is said to cure maladies as wide-ranging as malaria, delirium, and possession by the devil. The height of snake soup season comes at the start of the Chinese new year, when establishments in Hong Kong’s western districts are said to ladle out as many as a thousand bowls a day.

Cassava pie

Bermudians don’t have to worry about keeping warm in winter, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have Christmas traditions. Bermuda was settled by pilgrims that crashed into the island in 1609 on their way to Jamestown. They made do with the meager plants that could grow in its poor soil. For that reason, cassava, a starchy tuber, has remained a staple of the island’s food culture since. The root, which is quite bitter and must be ground, soaked and strained to remove the cyanide that it naturally contains, can be used as flour. On Christmas Day, this flour is used to make cassava pie, a baked meat pie, usually made with chicken or pork and seasoned with thyme and nutmeg or allspice. To overpower the bitter taste of the cassava, recipes for cassava pie call for copious amounts of butter, eggs, and sugar. Reheating a piece of pie the next day requires no additional butter in the pan, as there’s enough already in the mix to melt down and fry the pie all over again.

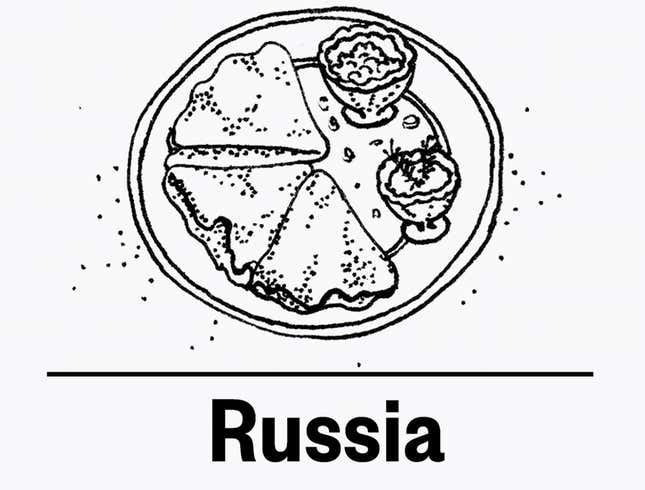

Blini

Springtime brings lots of traditional foods with it, and Maslenitsa, a Lent-type holiday celebrated in Russia when everyone eats crepe-like pancakes made of buckwheat flour, is no exception. Maslenitsa is the oldest surviving Russian holiday: archeological evidence suggests it originated on the vernal equinox as a pagan sun worshipping (thus the round pancakes) as early as the 2nd century A.D. But its seasonal date has since been bound up with the beginning of Orthodox Lent. The term “Maslenitsa,” which derives from “maslo,” meaning butter or oil in Russian, designates a full week, following vseednaya week (“omnivorous week,” with no limitations on diet) and ryabaya week (“freckled week,” with alternating ferial and fasting days), in which pancakes are eaten ritually every day. The pancakes are served with caviar, mushrooms, jam, sour cream, and of course, lots of butter. Pskov, a city of about 200,000 in northwestern Russia, has created a mascot for the holiday, the Czar Blin, a sort of friendly despotic “Hamburglar of Pancakes.”

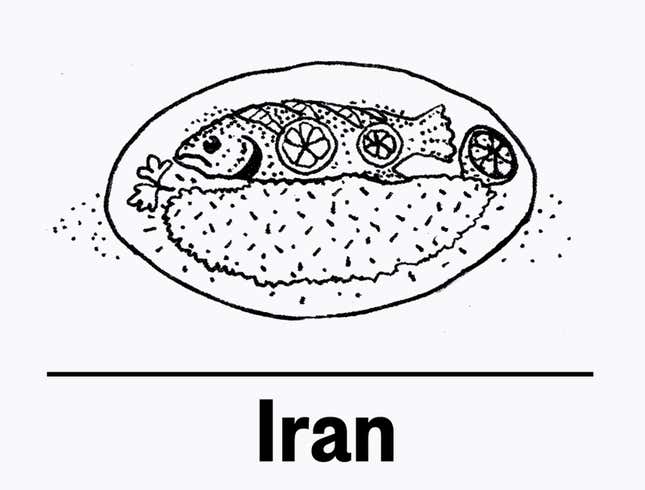

Sabzi Polo va Mahi

The Persian New Year, Nowruz, also falls on the vernal equinox, around March 21. The holiday is partially rooted in Zoroastrianism but it’s largely secular, celebrated by Persian-influenced peoples of various religions across the globe.

To celebrate, families prepare sabzi polo va mahi, a dish of fried white fish and herbed rice. The rice, polo, is layered with sabzi, a mixture of parsley, dill, cilantro, and scallions, then topped with cumin seeds and saffron.

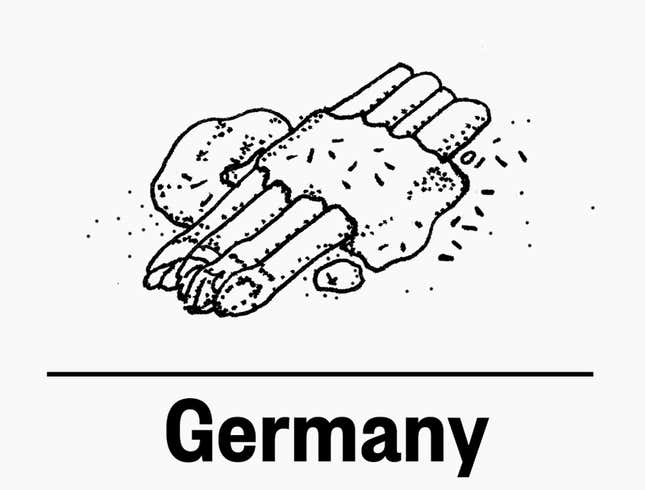

Spargel

For Germans, springtime doesn’t only mean the end of winter; it also heralds the “Spargelzeit,” the season when white asparagus is harvested. Certain regions of Germany, especially the southwest, are known for their white asparagus crops, which grow under the soil to prevent the vegetable developing its green chlorophyll.

The food is so popular in Germany that every newspaper and magazine carries Spargel recipes and some say that, at peak season, Germans are likely to eat asparagus at least daily. There are even traditional Spargel songs. Most Germans eat white asparagus peeled, boiled and drenched in hollandaise sauce, and served with boiled, salted potatoes. Germans are strict, too, about the length of the season: asparagus disappears from markets on June 24, on the feast of John the Baptist.

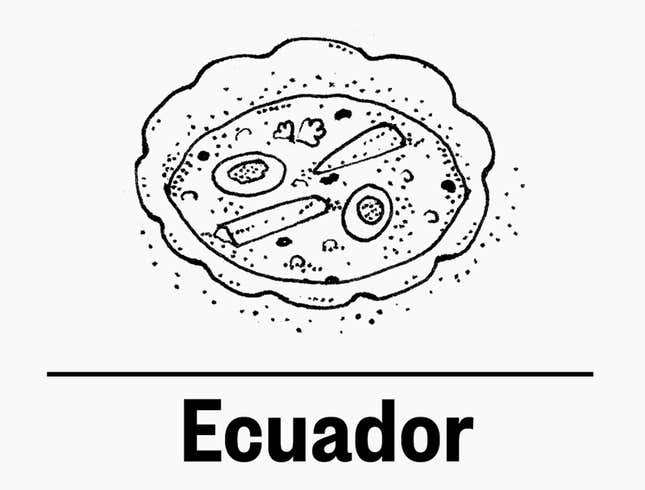

Fanesca

In Ecuador, the advent of spring is marked with fanesca, a thick, traditional soup made with abundant grains and salted cod. As in many Catholic countries, Ecuadorians forgo meat on Good Friday, and so fanesca is prepared with twelve grains and pulses (to represent the twelve apostles) including lupine, fava beans, lima beans, quinoa, lentils, corn, and peas.

The soup takes more than twenty-four hours to prepare and is only available during Holy Week. Ecuadorians wait all year for it, and it’s coveted abroad, too: Calvin Trillin, a famed food writer for The New Yorker, wrote in 2005 that his main impetus for improving his Spanish was to be able to tell the fanesca chefs, “I can’t take leave of this glorious establishment without saying, in utmost sincerity, that the fanesca I’ve just had the honor of consuming made my heart soar, or at least go pitter-patter, and I want to emphasize that each and every bean had a valiant role to play in what was, when all is said and done, a perfectly blended and modulated work of art.”

Biryani

India, a republic with 1.2 billion people, contains such a variety of traditions that it’s hard to find just one dish to represent the country. If there is one, though, it’s biryani, a mixture of rice layered with meat (usually chicken, lamb, or goat) cooked in an aromatic mix of ghee, nutmeg, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, bay leaves, coriander, mint, ginger, onions, garlic, and saffron. The dish is thought to be invented by Mughal emperors.

But a more symbolically apt food might stem from the festival of Diwali, also called the festival of lights, which is celebrated by Hindus, Buddhists, and Christians alike by the lighting of lamps and the eating of sweets. One of the most common sweets, a sticky paste made of condensed milk, flour and sugar, is known as barfi. Barfi can be mixed with many other flavors — ground cashews, almonds, or pistachios; rosewater or cardamom, or fruits like mango and coconut. On Diwali, barfi is often coated with a thinly hammered layer of silver (called vark) and cut into diamond shapes to represent prosperity.

Kushari

Kushari isn’t necessarily the kind of food that Egyptians eat on a holiday, but it’s a dish that’s authentically Egyptian, and found everywhere. In the 19th century, a strengthening Egyptian economy meant that even working-class families suddenly had access to more pantry staples that they had in the past.

Rice, macaroni, chickpeas, lentils, tomato sauce, onions, and garlic might all be left over at the end of the month, and these ingredients were soon combined into what is now sold at street-side stands as kushari: a sort of rice-and-macaroni pilaf mixed with lentils, topped with a spicy tomato sauce, and garnished with caramelized onion, lemon and red chili flakes. The fragrant tomato sauce incorporates coriander, cumin, clove, cardamom, paprika, nutmeg, and cinnamon.

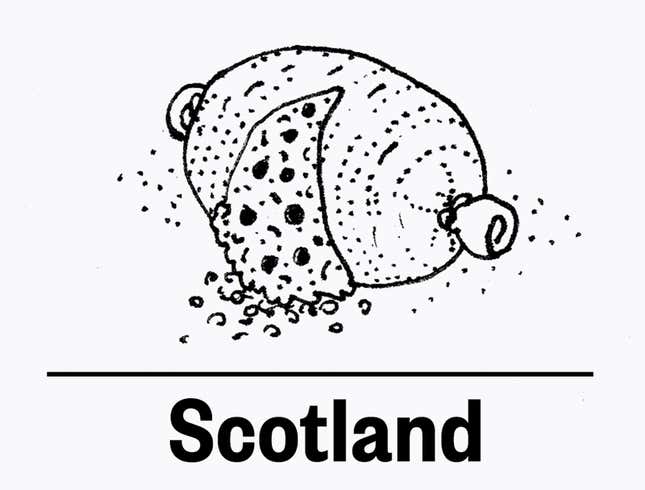

Haggis

“Great chieftain o the puddin’-race!,” Haggis is one of Scotland’s national foods. Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet, penned that line in his ode “Address to a Haggis” in 1786. Though Scots eat haggis throughout the year, they are sure to eat it on January 25th to honor Burns at a special Burns Supper.

Haggis is a savory pudding made of sheep’s heart, liver, and lungs, minced with onion, oats, suet (raw beef or mutton fat), spices, and salt, and stuffed into the animal’s stomach. The food has been banned in the United States for 43 years as part of a blanket embargo on foods containing sheep’s lungs, but not many outside of Scotland seek out the national dish. As Alton Brown at the Food Network recommends, “serve with mashed potatoes, if you serve it at all.”

Songpyeon

Koreans mark a three-day fall harvest festival called Chuseok, or Hangawi, with the ritual of making Songpyeon. Songpyeon is a dish made of glutinous rice flour cakes, called tteok, wrapped around sweet fillings like sesame seeds, honey, red bean paste, and chestnut paste.

Songpyeon is steamed and served on a bed of pine needles (“song” means pine needle) and gives off a telltale aroma that signals the coming of autumn. The rice cakes are said to resemble the harvest moon that heralds the start of the holiday. Koreans return to their hometowns to spend Chuseok with family, and so the holiday is known, in part, for the gridlocked traffic it causes across the country.

月饼 (Mooncakes)

The Chinese likewise celebrate an autumn harvest festival, one of the most important holidays of the year, by eating mooncakes. The cakes consist of a thin, pastry skin that envelopes a dense, sweet filling, often made from red bean, lotus, or jujube paste. (There are also salty and savory fillings, such as shark fin, seaweed, or ham.)

Some have a salted duck egg yolk at their center to symbolize the full moon. The casing is molded on top into a character, such as “longevity” or “harmony,” and often bears the name of the bakery that made it. The cakes are eaten in sliced wedges with tea, and can come packaged in colorful tins and boxes.

Wherever you may be, happy Thanksgiving from Quartz!