On Nov. 28, protesters across America boycotted Black Friday retailers to draw attention to police brutality in wake of the death of Michael Brown and the failure to indict the policeman who shot him. Noting that black Americans contribute over a trillion dollars to the US economy yet routinely have their civil rights violated, organizations asked shoppers to stay home so that corporations, and the politicians they often fund, will feel the economic impact. Protesters marched and chanted in shopping malls, staging “die-ins” in which they lay prone in imitation of victims of police shootings.

In the St. Louis metropolitan region, three malls were temporarily closed. The first, the Galleria, is in the commercial suburb of Richmond Heights and is popular with black middle-class St. Louisans. (On a map of St. Louis that went viral in April, this area was referred to as “where black people go to shop.”) The second, West County Center, is in the wealthy town of Des Peres in St. Louis’s affluent West County, and primarily serves white middle-to-upper class shoppers. The third, Chesterfield Mall, is the largest in the state of Missouri. A thriving commercial megaplex, it is even further out in West County, in an area populated primarily by wealthy white conservatives.

There were no mall boycotts near Ferguson, because there are almost no malls left to boycott.

The Black Friday boycott was called to bring attention to how little black lives are valued in America. One look around majority black North County, the area surrounding Ferguson, and this becomes clear. The malls of North County stand vacant, stores shuttered, weeds sprouting in the parking lot. “If we don’t get it, shut it down!” cried the protesters (referring to an indictment), but in North County, commerce was shut down long ago, leaving an impoverished majority black population without resources or job opportunities. This is the landscape of abandonment, where things crumble quietly and communities scramble to survive.

It was not always this way. North County was once home to several thriving shopping centers that opened in the 1960s and 1970s. One of America’s first shopping malls was the River Roads Mall in the city of Jennings, which borders Ferguson. In the 1980s and 1990s, when poor black families fled crime-ridden St. Louis City in search of a better life in North County, white families began to flee North County for the majority white exurbs. River Roads Mall, having no viable consumer base, closed in 1995—and the community lost the jobs and tax revenue that came with it. Today, Jennings makes the news for closing school in advance of the Ferguson grand jury decision, because it cannot afford a school bus to transport students through the area of Ferguson which ultimately burned.

In St. Ann, a small suburb near Ferguson where police have been locking up protesters since August, Northwest Plaza—later renamed The Crossings at Northwest—lies in ruins. Once the largest enclosed mall in Missouri, Northwest Plaza closed in 2010 after being acquired by the Australian corporation Westfield Group in 1997. As the demography of St. Louis shifted, with whites abandoning North County, stores began to pull out of Northwest Plaza, and Westfield shifted its investment to the malls in wealthy, white West County. Damaged infrastructure in Northwest Plaza was ignored for years, and in 2013, much of the complex was demolished. Today, impoverished St. Ann builds its revenue from traffic citations of a mostly black and Hispanic population. In 2013, St. Ann Municipal Court brought in $3.42 million dollars from fines, the most of any town in St. Louis County. A town stripped of its commercial base now profits off, and increases, the poverty of its own citizens.

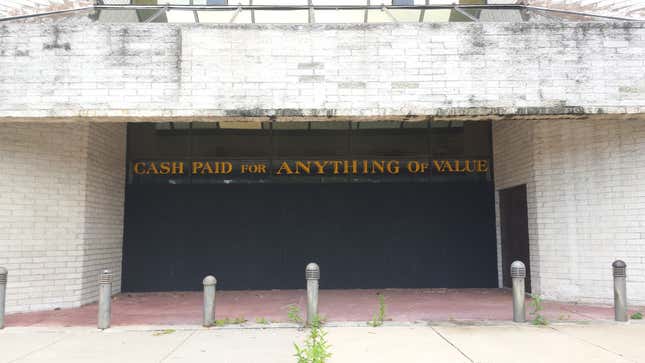

In Florissant, another city bordering Ferguson, the Jamestown Mall stands empty, a giant gold “Cash Paid for Anything of Value” sign looming over where an entrance once was. Jamestown is St. Louis’s most recently closed mall, having shuttered in July 2014, a casualty of the recession that never ended. By 2013, the mall was so poor the owners could not pay to heat it on Black Friday. By January 2014, Macy’s, the last remaining store in the mall, had closed, laying off 88 employees. They are among the thousands in St. Louis who have lost their jobs in the past decade as mall after mall collapsed.

The consequences of North County’s mall closures are far-reaching. In early 2014, I interviewed black North County fast food workers, most of whom took public transportation to their service jobs in wealthier St. Louis areas. North County residents who once had jobs nearby now spend hours on the bus, working for wages that do not even cover the cost of public transit. Displaced North County consumers face their own problems. When black shoppers of North County, now without a central destination, began going to the Galleria, their arrival was protested by parts of white St. Louis, some of whom sought to close the Metrolink transit station near the mall that opened in 2006. Concerns about Galleria “gang activity” prompted a panic that, by 2014, has proven wildly overblown.

Mall protests in St. Louis are not new. For years, Reverend Larry Rice, a champion of the homeless in St. Louis, has brought residents of his New Life Evangelistic Center shelter to malls in order to demonstrate the chasm between St. Louis’s rich and poor. In 2012, he proposed the Galleria be used as a shelter to protect the homeless in the scorching summer heat. St. Louis’s problems of poverty and racism long pre-date the events that drew attention to the region in 2014. But they remain, in spite of national attention, unaddressed.

In the region surrounding Ferguson, the real problem is that there is little left to boycott. Much of North County suffers quietly, commuting to wealthier suburbs as their own region is left to rot, their tax base erodes, and their officials derive revenue through racially-biased exploitation schemes. Opportunity, here, has long been in foreclosure. Apathy to the suffering of poor and black citizens has shut down more than any protest ever could.