Thanks to digital, news publishers thought they could build a direct relationship with their customers. Recent deals signal the opposite.

Two recent deals between media and technology companies struck me as a new trend in the distribution of news. One involves the personal note management service Evernote and Dow Jones (publisher of the Wall Street Journal and owner of the giant database Factiva); the other involves Spotify and Uber.

The first arrangement looks symmetrical. Based on the Evernote Premium user’s profile and current activity, an automated text-mining system—“Augmented Intelligence” in Evernote’s parlance—digs up relevant articles from both the WSJ and Factiva. A helpful explanation can be found on the excellent SemanticWeb.com quoting Frank Filippo, VP for corporate products at Dow Jones:

Factiva disambiguates and extracts facts about people, companies and other entities from the content that comes into its platform. With the help of Factiva’s intelligent indexing, “as users capture their notes, we detect if a company name is mentioned and dynamically present back a Factiva company profile with related news about that company” from any of its premium news and business sources.

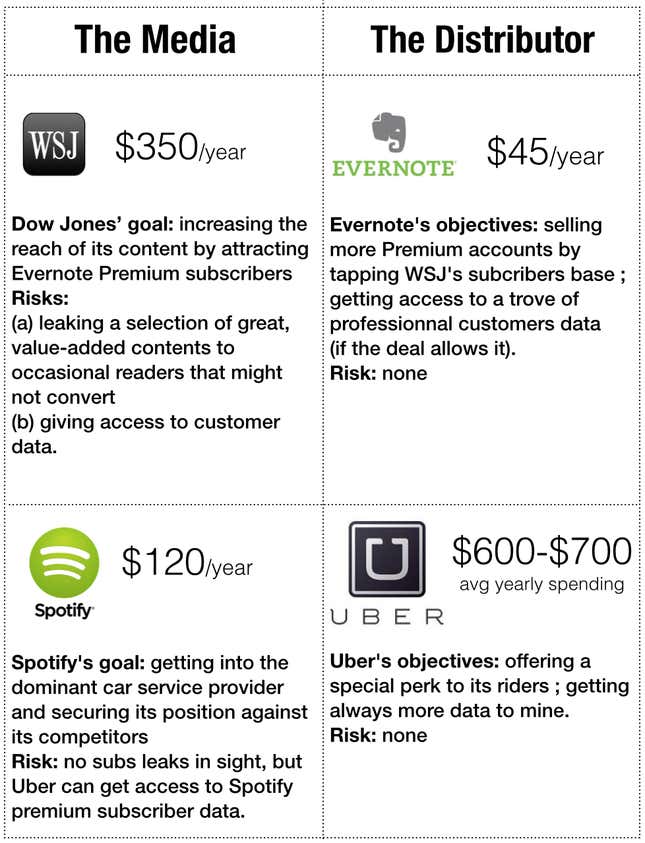

The deal is reciprocal: WSJ Subscribers who pay $347.88 a year (weird pricing) get one year of Evernote Premium (a $45 value); and Factiva subscribers are eligible for a one-year, five-login Evernote Business membership (a $600 value.) This sounds like a classic value vs. volume deal: per subscriber value is high for Dow Jones while it should allow Evernote to harvest more Premium and Business accounts at smaller ARPUs (average revenue per user.) At this stage—the service starts this month and for the US only—it’s unclear which company will benefit the most.

At first, the Spotify-Uber deal doesn’t look at all related to the news business. But it’s helpful for understanding a broader trend in the distribution of news products. The agreement provides that Spotify Premium users will be allowed to stream their music in participating Uber vehicles. In this case, respective ARPUs differ even more than in the DowJones/Evernote arrangement. A Spotify Premium account costs $10 per month while, according to Business Insider, the average Uber rider spends about $50 to $60 a month. To sum up, it looks like this:

In the these two deals, the advantage goes to the distributor. Without risking anything, Evernote get access to a valuable professional target group. As for the Wall Street Journal and Factiva, they push content that bears the risk of being more than rich enough for Evernote Premium users–without further need for a subscription to the Journal or Factiva. In this case, the key metric will be the conversion rate of users who are in contact with WSJ articles and opt for a trial subscription. (Based on past experience, publishers always overestimate the attractiveness of their paid-for content.) This doesn’t mean Dow Jones should have passed on the deal; every new distribution channel needs to be explored. As for Spotify/Uber, it shouldn’t move the needle for either partner.

Except for the data issues.

This is the key point in which parties may not equally benefit. Having dinner with a business predator like Uber requires a long spoon—a strong legal one—to determine the accessibility of stats and customer data. To me, this is much more critical than the difficult-to-assess financial parameters of such deals.

What’s next? There is no shortage of possibilities. Among many:

Deciding whether it is an opportunity or a danger for the news media sector is, to say the least, chancy. One sure thing: Digital technologies have successfully reconnected news media publishers to their customers. Some media outlets such as the Financial Times have successfully removed the intermediaries in the path to their audiences–whether these are B2C or B2B.

Today, everyone is worried about the unfolding of Facebook’s ambition to become the essential news distributor (see a previous Monday Note: How Facebook and Google Now Dominate Media Distribution.) In such context, letting other tech companies control too many distribution channels might create vulnerabilities. Possible ways to prevent such hazards are: a) bullet-proof contracts and b) approaching new distribution schemes in a collective manner. (That’s the science-fiction part of this column.)

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.