One of the strangest wars of modern times—a seven-year-long pipeline dispute that pitted the United States against Russia for influence in Europe—has ended.

The final chapter closed yesterday, when Russian president Vladimir Putin scrapped plans for a contentious project to supply natural gas to southern Europe. His decision was forced by the effects of Western sanctions, which in turn were prompted by Moscow’s nine-month-old invasion of Ukraine.

But the conflict’s conclusion was more or less already in motion, the result of what terminates most wars: utter exhaustion, not to mention the absurdity of the battle itself.

It all started in Baku

The story goes back to the 1990s, when the US decided to challenge Russia’s domineering hold on Central Asia and the Caucasus by championing the construction of independent oil and natural gas pipelines from these former Soviet hinterlands to the West. The idea was to give the ‘Stans, which were then only able to export their hydrocarbons through Russia, a measure of economic and political independence from Moscow.

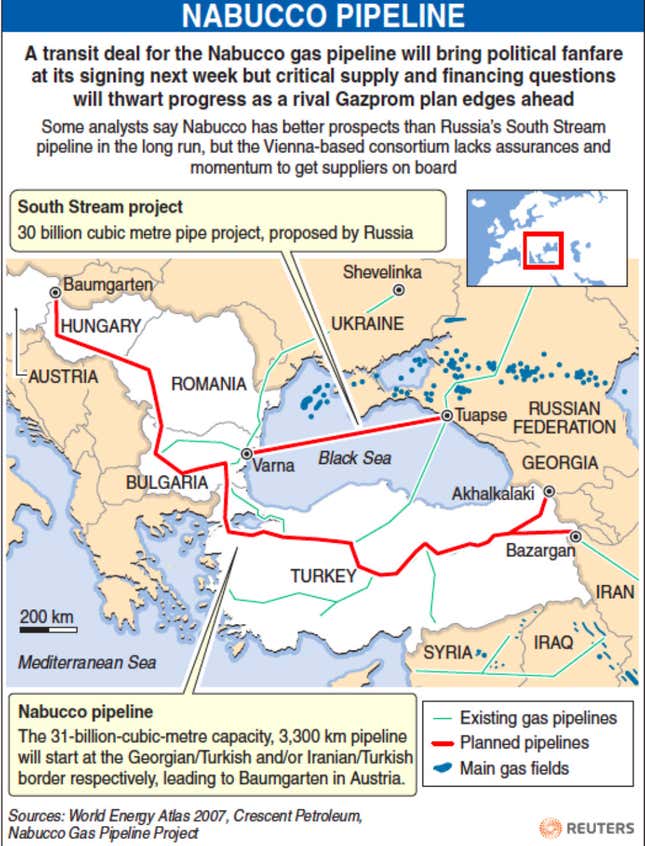

In 2006, the first line—a 1,000-mile oil pipeline—opened from Baku, Azerbaijan, to the Mediterranean. Not yet completed was the the natural gas line (later called Nabucco), which would connect up to Central Asia, beginning in Turkmenistan and following roughly the same course to Turkey and on to Europe.

A change of plans

It wasn’t long before the US understood that Turkmenistan wasn’t willing to ship its gas across the Caspian Sea, regardless of any pipeline. There was too much risk of igniting Russia’s ire.

So in the mid-2000s, Washington abruptly shifted Nabucco’s course. The pipeline would now begin not in Central Asia but in the Caucasus—starting once again in Baku. And the goal would no longer be greater independence for Central Asia, but to be an instrument of energy security for Europe.

The EU was in desperate need of some security, because in 2006, Russia shut off its gas supply as collateral damage from a Moscow row with Ukraine. Two more such shutoffs occurred over the next three years.

Introducing South Stream

In 2007, Putin—smarting over Washington’s oil triumph in Baku and not willing to let the US proceed unchecked—announced South Stream, a rival natural gas line to Nabucco. South Stream would serve more or less the same European customers as Nabucco, so it was clear from an economic standpoint that only one of them could actually be built.

So began the pipeline war, probably the first such conflict in history. Here is how the rival pipelines were sized up at the time.

Putin was the chief general

This was largely a diplomatic fracas, but Putin himself led the way on the Russian side. He flew around Europe with his protégés, wooing South Stream partners with great success. On the corporate side, Germany’s gigantic chemical company BASF signed on, as did France’s EDF and the Italian oil company Eni. Serbia became a huge South Stream champion, as did Bulgaria and Hungary. In December 2012, the allied countries held a ceremony in southern Russia with the symbolic welding of the first length of pipe.

The US, led not by its presidents but its diplomats, was also indefatigably campaigning for Nabucco. But unlike South Stream, whose gas would come from its operator (Russia), Nabucco had to find gas, which turned out to be hard to come by. And it became even harder when the world suddenly changed under Nabucco’s feet: the shale revolution began, resulting in a glut of natural gas around the world. Europe was still reliant on Russian gas, but it was now also receiving a large supply of liquefied natural gas from Qatar.

Nabucco was starting to look a lot like a pipeline without a cause. In June 2013, it finally succumbed when gas producers in Azerbaijan, its source of last resort, decided not to commit any supply to the pipeline. Nabucco was declared dead.

But the fighting wasn’t over

The original rationale for South Stream—to beat Nabucco—had now vanished. But Putin crusaded on. As recently as Nov. 19, Hungary said it was going to start construction of its stretch of the pipeline in 2015 with an eye on South Stream being finished two years later.

But with the invasion of Ukraine, the EU—for years weak-kneed against Russia—finally bared its teeth and pressured its members to stop supporting South Stream.

On Dec. 1, Putin—on a trip to Turkey—conceded that the West had won. After $9.4 billion in spending by Gazprom, South Stream was finished, too.

Putin purported to have another card up his sleeve. Yesterday he announced a new pipeline partnership: Russia would build yet another gas pipeline, this one to Turkey. But the announcement lacked the panache of its antecedants—the new pipeline had no name, no length, no price. The world’s first pipeline war ended up having no victors at all.