The divorce rate in America is rising. Do you think that statement is true? If you do, you’re not alone. As Claire Cain Miller recently pointed out in an article for The New York Times, we hear about the rising divorce rate in the news all of the time. This is curious, because as it happens, the divorce rate isn’t rising.

By most measures, the divorce rate in America has been declining since around 1980. You’d think that something as simple as counting the number of American marriages that end in divorce would not require the qualifier “by most measures,” but it turns out that there is no universally accepted method for doing the counting. For instance, the widely quoted 50% divorce rate in the US probably came from a best-guess prediction that has yet to come true, or from a shortcut method of comparing the number of divorces and marriages in the same year. This is not considered to be an accurate method for assessing the divorce rate because it does not compare equivalent groups. In 1980, for example, older couples may have been divorcing at a high rate because of the introduction of no-fault divorce laws, while younger couples might have been putting off marriage because more women were pursuing careers. Even if the number of marriages that year were twice the number of divorces, that is not the same thing as saying that half of all marriages end in divorce. As for the prediction model, Dr. Rose M. Kreider, a demographer in the Fertility and Family Statistics Branch of the Census Bureau, told the New York Times in 2005, “At this point, unless there’s some kind of turnaround, I wouldn’t expect any cohort to reach fifty percent, since none already has.”

Even if everyone could agree on the best way to calculate the divorce rate, complete demographic data about marriage and divorce are unfortunately no longer available for analysis. In 1996, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) stopped collecting yearly statistics on marriage and divorce due to budgetary considerations, and some states, such as California, do not report divorce rates. The Census Bureau can provide estimates based on questionnaire data, but this relies on self-report, and people are reluctant to provide information about marital status. The quality of data available for analysis is therefore weaker now than it has been in past years.

Despite the paucity of good data and arguments over statistical calculations, most social scientists and demographers would agree that divorce rates are declining or stable, that a 50% divorce rate has not yet come to pass, and that young couples today are so far on a course to have fewer divorces than their parents’ generation. Why, then, do we keep hearing about rising divorce rates in America?

One of the reasons is that a rising divorce rate fits the world view and agenda of some segments of our society, whereas a falling divorce rate doesn’t fit as neatly into anyone’s agenda. If you self-identify as conservative, you may have had a negative reaction to this article so far, because it seems to be saying, “High divorce rates are no big deal, and reports of the marriage crisis in America are overblown.” On the other hand, if you consider yourself to be liberal, you may be thinking, “Some couples need to get divorced. Should that be half the number of couples who are divorcing now or twice that number? I don’t know.” In other words, people who see divorce as a social scourge want to emphasize how dire the situation has become in America, and people who see divorce as a necessary evil don’t worry too much about the divorce rate.

This dynamic plays out in the popular press, where much of the news about marriage and divorce is derived from the National Marriage Project, founded at Rutgers University in 1997 and now based at the University of Virginia. A core mission of this organization is to “identify strategies to increase marital quality and stability.” In support of its mission, the National Marriage Project creates a sense of crisis around marriage and divorce rates and promotes marriage as a solution to a range of social problems (pdf).

According to Philip Cohen, a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, the media have become hooked on publications from the National Marriage Project as a quick and cheap sources of easily digested print. This would not be a problem if media outlets disclosed the biases of their source, but as noted in our book Sacred Cows, that doesn’t usually happen. For instance, between 2009 and 2012, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Times, USA Today and the New York Times all published articles originating from a report by the National Marriage Project claiming that the economic recession was saving marriages.

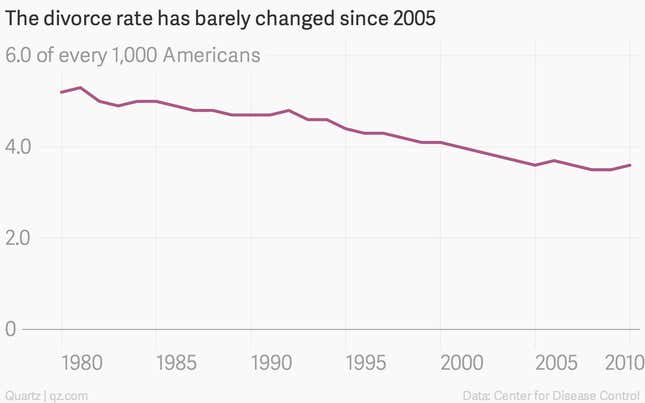

The evidence provided was that divorce rates fell between 2007 and 2008 after rising from 2005 levels. We have graphed the crude national divorce rate, or the number of divorces per 1000 members of the US population, for those years. Note that this measure of the divorce rate, like all measures, is flawed. Because it uses the total population as the base, it includes children and unmarried adults, which confuses interpretation; a lower divorce rate could result from a baby boom, or more pertinent to the current situation in the US, a lower marriage rate. The other problem is that several states have discontinued reporting divorces, and missing state numbers could distort the overall national profile.

Bearing in mind these limitations, our chart does indeed demonstrate that the divorce rate declined after the great recession began in 2007. However, when taken in context of overall trends and year-to-year variability, this change in divorce rate does not seem significant enough to warrant multiple stories in major national newspapers

(California, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Louisiana, Minnesota and Oregon have data missing from some of the years in the chart.)

Based upon rather odd logic, the director of the National Marriage Project, W. Bradford Wilcox, stated that thrift and meals at home were the cause of recession-strengthened marriages. It may well be that fewer people divorce during economic recessions; the data on that subject are murky and conflicting. However, a one-year blip in the divorce rate should not be used as evidence that the divorce rate is rising any more than a subsequent blip should be used as evidence that economic hardship makes marriages stronger.

Promoting marriage is not a bad goal. Most people would like to be happily married. It is also completely reasonable to worry about so many American marriages ending in divorce. No matter what the circumstances, divorce is painful for families and communities. The problem is that social and political agendas have muddied the water so much that we can’t have reasonable discussions based on rational facts. We are all being misled, not just about the trajectory of divorce rates in America, but about every aspect of our lives that powerful special interest groups care to manipulate. In the words of sportscaster Vin Scully, statistics get used much like a drunk uses a lamppost: for support, not illumination.

In an ideal world, we could rely on a free press to present unbiased information in a thoughtful and measured fashion. We don’t live in that ideal world, but perhaps we can start by requesting improved transparency and disclosure by popular media about the biases of its sources. To that end, here is our disclosure: This article represents the opinions of two left-leaning egghead authors of a book about society’s attitudes surrounding marriage and divorce. Our goal is to promote rational discussion about marriage and family life in our country. Unfortunately, we can’t provide a single definitive statistical analysis of divorce, because none exists. But hopefully we have helped to clear up a small, persistent misapprehension: The divorce rate in America isn’t as high as 50%, and at least for the moment, it isn’t rising.