On the night of April 8, 1988, in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston, a teenager named Mark Wahlberg wanted some beer—badly. So badly, in fact, that he attacked a man carrying two cases of beer, bashing his head open with a five-foot-long stick. A few blocks later, Wahlberg punched another man in the eye, blinding him. After his arrest—during which police found him carrying a small amount of marijuana—Wahlberg called his victims ”slant-eyed gooks” and other ethnic slurs. Though 16 at the time of the assaults, Wahlberg was convicted as an adult and sentenced to three months in prison, reports the AP. He was released after serving about 45 days.

His past hasn’t barred Wahlberg (as “Marky Mark”) from a platinum single, or from Times Square beefcake billboards. Nor from becoming an actor praised for his work in Boogie Nights, The Departed, and other films. Wahlberg, now 43, is one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood, and his company has produced popular TV shows such as Entourage and Boardwalk Empire.

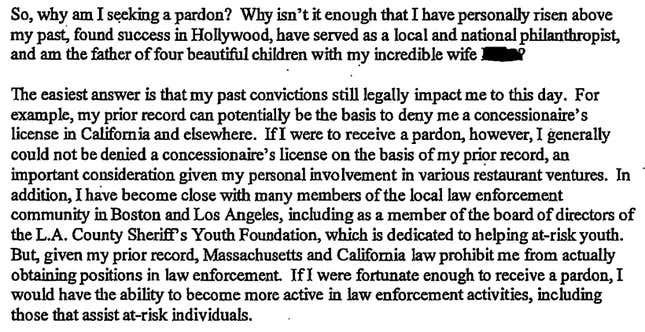

But his criminal record has prevented him from getting restaurant licenses in some states, and made him unable to conduct philanthropic work with at-risk youth. This is why Wahlberg is asking the governor of Massachusetts to pardon his convictions, according to his application (pdf):

Wahlberg shouldn’t get a pardon.

Not because his crimes were so heinous. Though they certainly were—and the two assaults in 1988 weren’t even the extent of them. As The Smoking Gun reports, a 15-year-old Wahlberg and two friends attacked a group of black schoolchildren, hollering the n-word at them. And in 1993, he and a friend battered a man so severely that the victim’s jaw had to be wired shut.

And not just because people seldom get pardons, even for 25-year-old crimes. If Massachusetts governor-elect Charlie Baker and the Governor’s Council pardon him, it will likely be because of his celebrity, not his contrition.

Not even because, at a time when so many white men seem to be above the law when it comes to violence against non-whites, pardoning Wahlberg would send a message that whites can do wrong with impunity.

He should not be pardoned, because, instead of pardoning him, state and federal governments should ease laws that prevent convicted felons like him from fully participating in society—that let past convictions for which felons have already been punished continue to “legally impact” them, as Wahlberg put it, for the rest of their lives. These laws bar ex-offenders from a whole host of things, from opening a restaurant or obtaining public housing to being eligible for student financial aid.

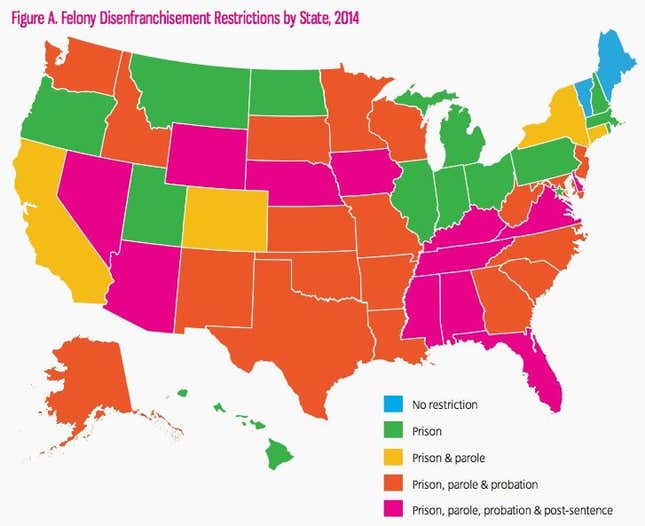

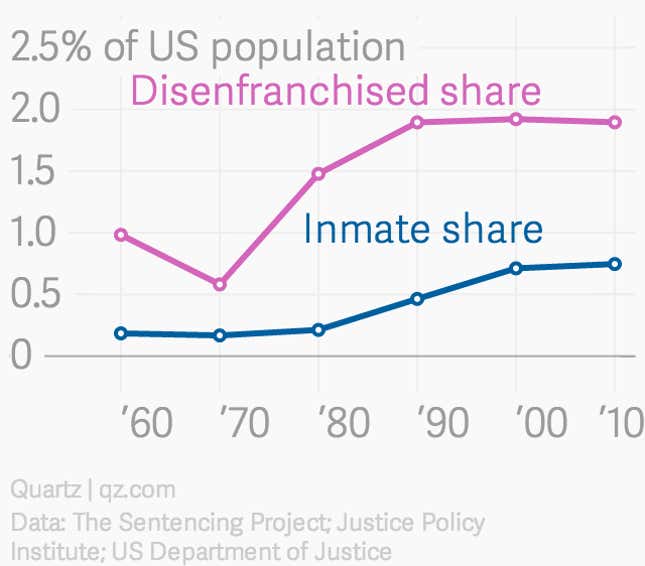

Around 5.9 million Americans are barred from voting because they have felony convictions, says the Sentencing Project (pdf), a non-profit advocacy group. If Wahlberg lived in Nevada or Kentucky, for instance, he wouldn’t be allowed to vote at all.

This systematic disenfranchisement disproportionately affects black people. For instance, in Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia, more than one out of every five black adults is not allowed to vote, says the Sentencing Project.

Even though he’s a silver screen mega-star, Wahlberg is still affected by a vast latticework of laws and practices that makes it hard for ex-offenders to find jobs. As Wahlberg has discovered, his assault felony bars him from working with “vulnerable individuals,” including in childcare, healthcare, and education.

Wahlberg’s ineligibility for running restaurants in California and other states is an example of the sweeping barriers against ex-felons hoping to work in licensed industries. In New York, for instance, licensing rules against ex-offenders bar them from becoming barbers, cosmetologists, and real estate agents, says Alyssa Aguilera of VOCAL-NY, a grassroots organization focused on HIV, drugs, and incarceration.

If Wahlberg’s six-pack and clunky rapping hadn’t launched his early celebrity, he’d likely have joined the ranks of what are now 70 million people—one in four American adults—who struggle to find work due to past arrests or convictions.

Unemployment rates for offenders a year out of prison are around 60 to 75%. One 2009 study (pdf) in New York City found that a criminal record reduces the likelihood of a callback or job offer by half, and even more so for black candidates. Though a number of states limit employers’ use of arrest and conviction records in making hiring decisions, a majority don’t. And while excluding every candidate with a criminal record is generally illegal under federal law, enforcement favors employer discretion.

This crimp on male employment is also bad for the US economy, contributing to an estimated loss of up to $65 billion in output (pdf), according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Those that can’t get jobs have to make money somehow, which likely explains why employment is a major factor in slashing recidivism (paywall).

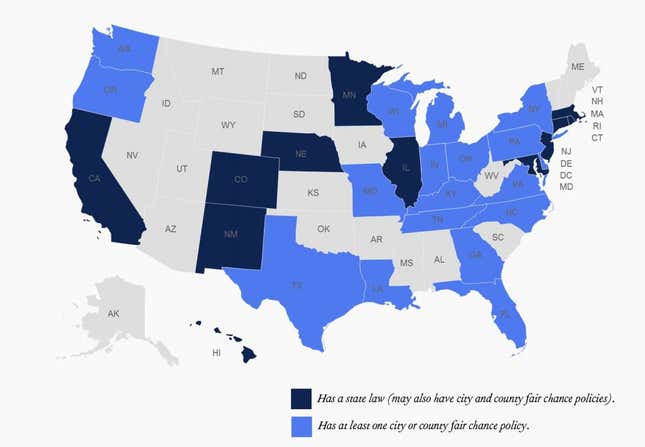

This is slowly changing; in the last few years, at least 13 states have “banned the box,” as it’s called, striking the felony conviction box from job applications. Reform on voting rights is gaining momentum too. But poor ex-offenders in particular still face colossal hurdles to re-entering society, says VOCAL-NY’s Aguilera. “Employment, housing, and democracy are pretty major things in people’s lives,” she says. “So [these laws] end up having an impact on what your potential is.”

Some argue that because the 70 million other ex-offenders still have to suffer the consequences of this bigotry, that Wahlberg deserves no special treatment just because he’s rich, famous, and white. But do people really think Wahlberg’s past—violent and racist as it is—has any bearing on whether he should be allowed to sling fancy burgers and help kids?

If anything, Wahlberg’s plea for such mundane rights is a rare reminder of how profoundly this prejudice against ex-offenders is embedded in federal and state law. In that sense, the problem isn’t so much Wahlberg’s gall in asking for what seems like special treatment by the system; it’s the system itself. Wahlberg does indeed deserve the same thing as those tens of millions of other Americans: better.