On Nov. 30, dozens of protesters took to the streets of St. Louis’s south side to decry the killing of an innocent man. Waving signs that read “no justice, no peace,” the grieving community marched, blocking off a major intersection. St. Louis police arrived in riot gear only to discover that this was not one of the Ferguson protests that had been popping up around the metro area. That morning, Zemir Begić, a 32-year-old Bosnian immigrant, had been beaten to death by teenagers wielding hammers. The Bosnian community of St. Louis—at roughly 70,000, the largest in the US—was not protesting the police: it was demanding their attention and protection.

News of Begić’s violent death emerged as St. Louis was reeling from the grand jury decision and its tumultuous aftermath. Right-wing pundits who had never expressed much interest in the welfare of St. Louis’s Muslim Bosnians pounced on the case, portraying it as a sort of anti-Ferguson: a white man murdered by non-white teenagers (three black, one Hispanic), mourned by a community who valued police instead of vilifying them.

On the ground in St. Louis, where an aggrieved and grieving community balances political frustration with day to day living, the reality is more complex.

“It was black teenagers attacking a white guy. That’s just the world we live in,” Almedin, a 23-year-old Bosnian refugee who did not give his last name, told Quartz. “With the whole Ferguson thing, if people started saying it was a hate crime, it would start a race war. That is the last thing anyone wants. You’ve got white people protesting with the blacks in Ferguson, coming together. I like that. I don’t like seeing anyone’s rights get violated. And there is no question they are violated.”

Bevo Mill is a St. Louis neighborhood that was once an underpopulated, nearly abandoned area with dirt-cheap rents. It became home to tens of thousands of Bosniaks—ethnically Bosnian Muslims, not only from Bosnia and Herzegovina but other areas in the Balkans—and Roma war refugees relocated during the 1990s.

Over two decades, they rebuilt the neighborhood in their own image: Bosnian restaurants, newspapers, mosques and bars.

This revitalization of Bevo Mill has been heralded as a St. Louis success story: proof of positive transformation in a region battling a decades-long decline. But for many Bosnians, the road has been as traumatic as it has triumphant. Begic’s murder follows the 2013 murder of 19-year-old Haris Gogić, who was killed during a robbery at his family’s store. Gogic’s funeral drew over 3,000 people.

“Bosnians come from a war zone,” explains Džemal Bijedić, a police chaplain from Sarajevo who is one of only six Bosnian police officials in the St. Louis metropolitan area. “Two hundred thousand of us were killed. Many of us lost our families. The majority of people here have lost someone, or were in a concentration camp, or were tortured.”

After two brutal murders in two years (on top of other crime), several Bosnians from Bevo Mill expressed the feeling that in coming to St. Louis, they had exchanged “one war zone for another,” saying they feared letting their children walk to school. Shopkeepers said they were hiring extra security to protect customers. Some talked of leaving St. Louis city for the southern suburbs, where, as one local told us, “you can walk on the street without worrying about being killed.”

Though shaped by particular trauma, this worry is not unique to the Bosnian community. As handgun sales and homicides both rise, crime—and who is assumed criminal—is on the mind of St. Louisans.

In St. Louis, discussion of crime is inseparable from the issue of race and racial bias. Begić was the 136th person killed in St. Louis in 2013, and since he died on Nov. 30, 11 more people have been killed. That brings the number to 147, well above the 120 homicides of 2013. Though police and politicians have pinned cause to Ferguson tension, homicide rates have been rising since April, four months before Michael Brown was killed by Darren Wilson. A disproportionate number of homicide victims and perpetrators are black.

“What about black on black crime?” is the de facto derailment of conversation on Ferguson. A disproportionate number of homicide victims and perpetrators in St. Louis are black. Like much else in St. Louis, violent crime is segregated, with most crime occurring in impoverished black neighborhoods whose everyday problems are rarely covered by the news. When it is not—as in the Begić case—anxieties about race are inflamed.

For the Bosnian community, predominantly Muslim, race is a complicated subject. Bosnians entered the St. Louis area at a time of deep division. The south city area where they moved upon their arrival was populated by two groups: lower-class blacks, some of whom considered Bosnian traditions strange, and lower-class whites, some of whom considered Muslims suspicious—and not quite “white enough.” Bosnians struggled with an uncertain racial identity in a racially polarized community. After 9/11, hostility toward Muslims in the region increased.

“For the time being, probably the most honest answer to the question of whether Bosnians perceive themselves as white is ‘We’re not sure,’” says Jasmin Mujanović, a Bosnian political scientist who notes that American history is full of immigrants—Poles, Irish, Italians—who became “white” only decades after arrival. “I suspect, ultimately, any definitive shift towards ‘whiteness’ among the Bosnian population in the US—when they will self-identify as ‘white people’—will come if or when there is a political need for it, as has historically been the case with other communities here,” he told Quartz. ”Given the recent events in St. Louis, however, that could (unfortunately) change very quickly to a definitive ‘yes.’”

Many local Bosnians echo this assessment. “Bosnians aren’t completely looked at as white,” Almedin told Quartz. “But it’s different when it’s a crime. No one is going to come up to you before robbing you and ask about your ethnic background. Here, white is white and black is black.”

Almedin, like many other Bosnians, believes Begić was targeted not for being Bosnian, but for being white. He and others in the community claim anti-white racial epithets were shouted before he was killed. “Police are saying there is no motive,” he continues, “but what other motive could there be?”

St. Louis police, including Bosnian officials, dispute that race played a role in Begić’s murder. “People say black/white. I don’t say this,” Bijedić told Quartz. “A lot of black people are crying about this. You can’t say black/white about this. We do not know yet if this is a hate crime. The investigation is ongoing.”

Bijedić emphasized that Bosnians are protesting not only for more police in Bevo Mill, but for better police—police that understand the needs of a diverse community. In some ways, their complaints echo those expressed by black residents of Ferguson.

“Everyone needs improved policing,” he says. “Not all police are bad. Not all citizens are bad. No one is perfect. We have to talk as civilized people, examining the issues and seeing what we can do. We need someone to train police on how to deal with different ethnic groups, how to interact with people of different nationalities. But we are told the city does not have the money.”

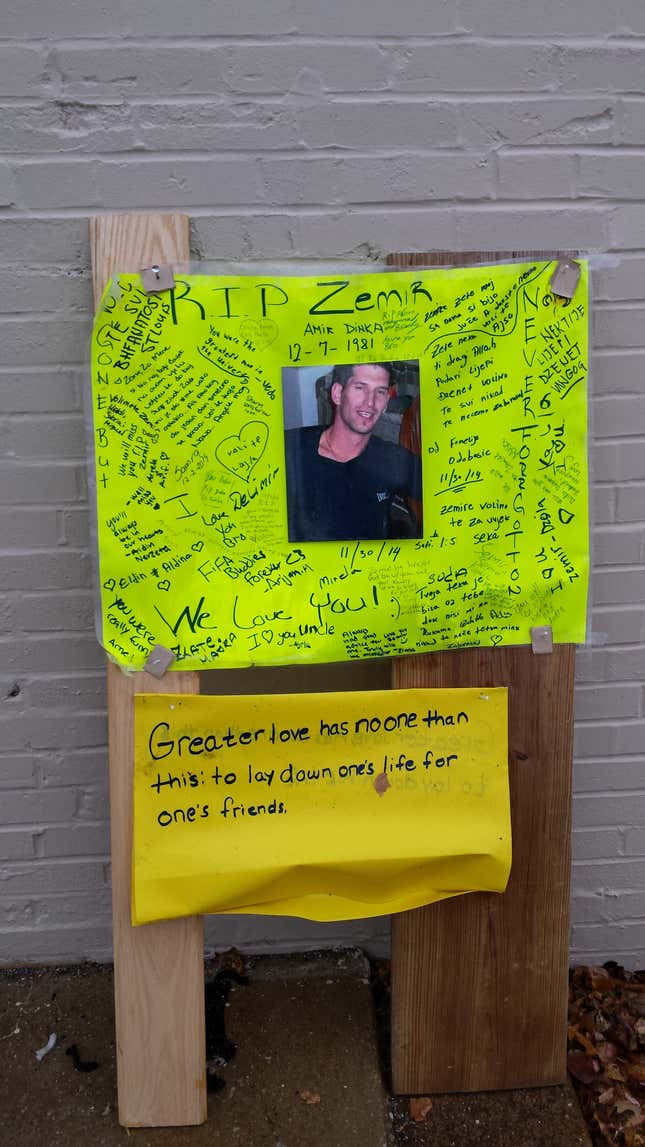

A memorial for Begić is located at the intersection where he was killed and the protest was held. “Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends,” read a handmade sign, the Biblical passage referring to Begić’s efforts to protect his fiancé, Arijana Mujkanovic, before he was murdered. Mujkanovic says her finance, a singer who had recently moved to St. Louis, pushed her out of the way of the assailants as a final act of valor. Candles, teddy bears and balloons, left by a grieving community, surrounded it.

Many will try to use the tragic death of Begić to further inflame tension in an already anguished region. On Dec. 5, another Bosnian was attacked, and the incident is being tentatively investigated as a hate crime.

But visiting Begić’s memorial tells a different story: four days after the murder, a black, middle-aged couple approached, holding a teddy bear and a balloon. With tears in their eyes, they placed the items at the memorial and walked away.

Empathy isn’t black nor white. All St. Louisians are wondering when the pain will stop.