In recent years, America’s oil and gas sector has flared brightly against an otherwise gloomy economic backdrop.

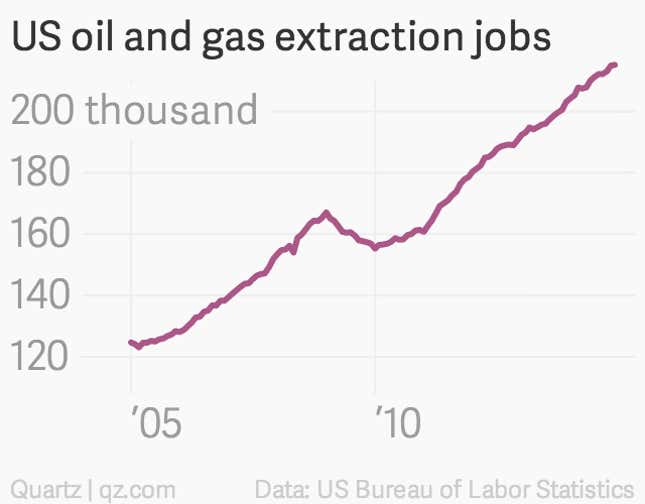

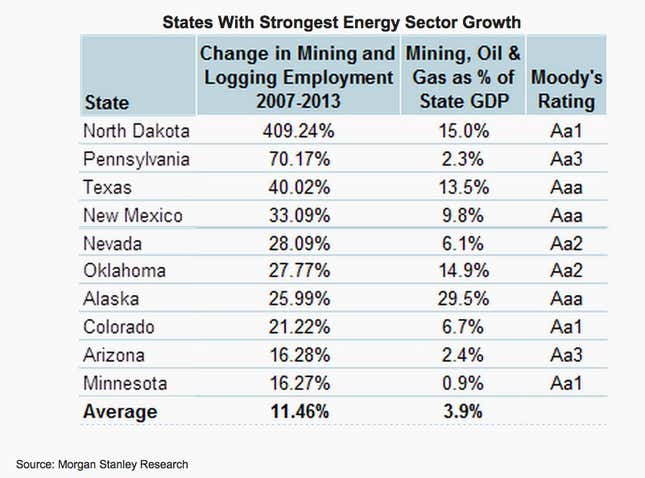

Since the end of the Great Recession, the number of jobs in oil and gas extraction—not counting related industries such as transportation—has jumped 35%, while total US jobs have risen only 7%. Unemployment in energy-producing states, especially those involved in the shale oil boom, has collapsed to some of the lowest levels in the country. Investment in drilling has supercharged sales of heavy machinery and GDP in general. And the gas patch has been one of the few places in the country where working Americans have gotten healthy raises in recent years.

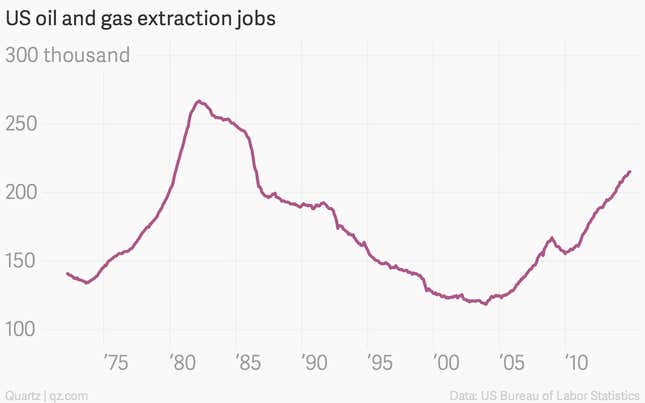

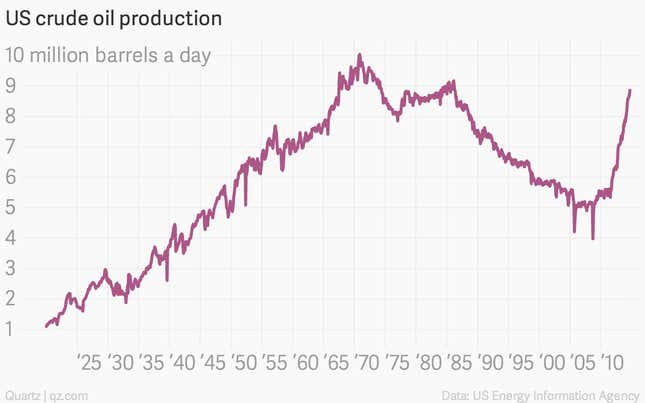

That might make the climb of energy employment, production and investment seem inexorable. But that’s just if you’re looking at the last few years. When we pull back for a wide-angle view, you can see this is just the latest chapter in a much longer story.

The umpteenth boom

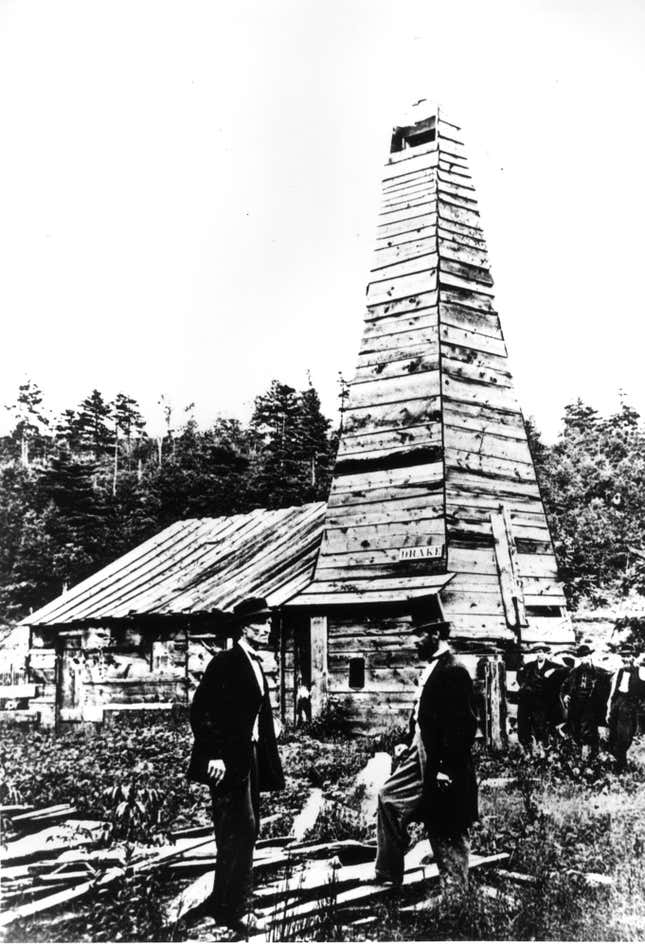

The US has gone through any number of oil booms and busts since Edwin Drake sank the world’s first oil well in 1859 in Titusville, Pennsylvania. It became the test case for subsequent boom-bust cycles. Oil production surged far ahead of demand—which was then largely to confined to kerosene for lighting—and oil prices, which had been above $10 a barrel in 1860, crashed to 10 cents by late 1861. Land values plummeted. Whole towns, such the Pennsylvania town of Pithole, vanished. But from that first violent cycle, the oil industry was born.

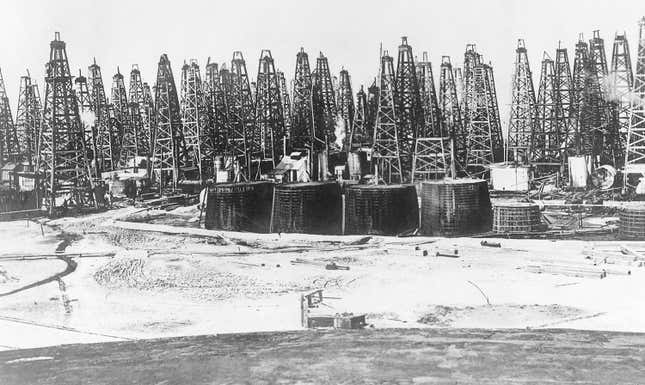

Along with it came the near-constant challenge of mastering the volatile swings in supply and demand that characterize petroleum production. After Western Pennsylvania’s bust, Ohio enjoyed a boom centered on the town of Lima, beginning in the late 1880s. In 1901, the great Spindletop oil strike near Beaumont in East Texas marked a new high point—as did, in turn, other great strikes in Cushing, Seminole and Signal Hill.

Around the turn of the century, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil hit on the solution to price volatility: Buy and control the whole industry. Rockefeller’s trust dominated until 1911, when the Supreme Court found Standard Oil to be violating antitrust law, and broke it into 34 independent companies scattered across the country.

In the 1930s, the discovery of the “Black Giant” field in East Texas cratered oil prices yet again. They fell so low that the entire industry was in question during the later stages of the Great Depression. It was saved only by a series of Depression-era price controls, state intervention, and tariffs on foreign oil.

But the key to understanding today’s collapsing energy prices (Brent crude, the global benchmark, is down more than 40% this year) is perhaps the US oil-and-gas bust of the mid-1980s.

What happened?

The OPEC backlash

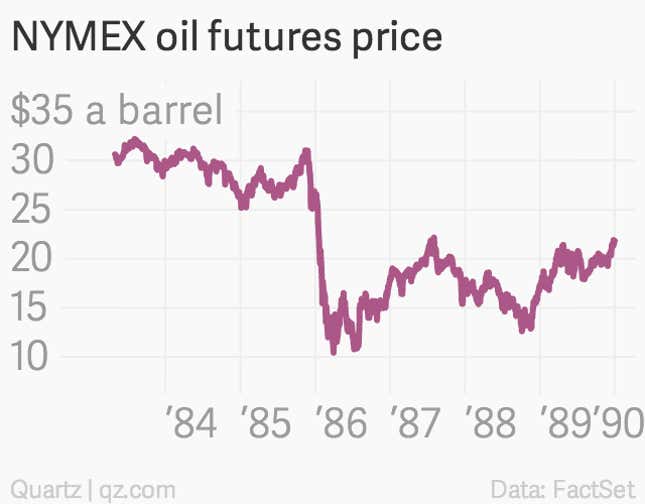

Simply put: It was a good old-fashioned price war led by Saudi Arabia. In the early 1980s, a surge of non-OPEC production centered in the UK’s North Sea and the US was forcing prices downward, just as conservation and new forms of energy such as nuclear were eating into oil demand. The members of OPEC—the oil-price cartel organized in 1960—faced a choice. They could defend the price of oil by limiting production, which would cost them market share. Or they could preserve market share by cutting prices. For a while they tried the first approach. But the discipline of the group broke down, as some oil exporters exceeded their production targets to take advantage of the higher price. Others—foremost among them Saudi Arabia, the world’s most important producer—stuck to the targets and saw themselves losing revenue.

In late 1985, Saudi Arabia decided it had had enough, and decided to stop adhering to production limits. It was as if someone had flipped a switch. Oil plummeted, falling from more than $31 a barrel in late 1985 to roughly $10 a barrel.

That put an abrupt halt to the surging fortunes of the then-swaggering US energy sector (embodied in the character of duplicitous J.R. Ewing on the long-running US soap opera Dallas.) With oil prices suddenly so low, investment dried up. Production sank. Unemployment rose. And losses mounted to the point where they bled into the US financial system. During the good times, banks had competed feverishly to lend to wildcat oil producers. But when prices dropped, these oil companies couldn’t service their debts. That fact, along with the quickly cratering regional economy, rendered hundreds of banks insolvent (pdf).

The repercussions went far further than the gas patch. Even before the Saudi-induced price collapse, the failure of an over-enthusiastic Oklahoma bank—Penn Square, whose head of energy lending, Bill Paterson, was famous for drinking amaretto out of his Gucci loafers—dragged down Continental Illinois, then the seventh-largest bank in the US. It had to ask for a federal bailout. And ultimately, rock-bottom oil prices precipitated the demise of the Soviet Union (pdf), which was heavily reliant on oil revenues.

That sinking feeling

Today, the backdrop of the mid-1980s bust seems strangely familiar. In the US, production is surging. Globally, demand is slumping. And Saudi Arabia seems willing to tolerate low oil prices. Already there are signs that the drilling activity in Texas is starting to slow (though production tends to take longer to decline, since energy firms will try to squeeze all the cashflow they can out of wells where they have sunk costs.) And while the regional banks seem to have been more sober lenders—thanks in part to more aggressive regulation—during the recent boom, it’s clear that there will be some pain beyond the oil industry.

For example, investors in US junk bond markets—heavily weighted toward the energy sector—have been hammered this year. The energy sector of the benchmark Barclays Aggregate bond index is down roughly 15% in 2014. Markets are growing increasingly skeptical that Venezuela, where oil brings in 95% of export revenue, will be able to service its debts; its government bonds are at a 16-year-low.

And while the Russian state has very little debt itself, state-backed oil companies have massive liabilities that must be rolled over, and zero access to international capital markets, thanks to the sanctions in the wake of the conflict in Ukraine. Meanwhile, inflation and interest rates are rising, which further hampers the fast-weakening Russian economy.

In the US, there will clearly be a slowdown in the fast-growing energy states (see table). That will hurt GDP growth, which has been driven by oil and energy investment.

The counter-cycle

But for the US as a whole, a decline in the energy business is actually welcome. Texas and the rest of the oil patch often operates almost as a parallel economy to the country as a whole. During the early part of the Great Depression in the 1930s, the East Texas oil region was booming. When the US economy was desperately attempting to deal with the global oil shocks of the 1970s, the US oil industry was living large. Even over the last few years, the economies inside and outside of oil-producing states have been polar opposites.

In other words, the energy business doesn’t decide the fate of the US economy. American consumers do. (The decline in consumer gasoline prices could mean savings of as much as $750 over the next year for the average American family.)

So while the industry has offered cherished growth to the economy during the worst of the recent recession and sluggish recovery, don’t expect Americans outside the oil industry to mourn the bust if it comes. If history is any guide, it probably will.