Many of the students now applying to US colleges and universities have almost no idea what it will really cost to go there, should they be accepted.

Save the jokes about these kids needing to do their homework. This is not the fault of prospective students—or their families.

If transparent pricing is the key to a healthy market, the US higher education industry should be in an iron lung. Sticker prices for university tuition and fees have surged roughly 1200% since 1978, far outpacing the overall 280% inflation over the same period. The average cost of a year of private school tuition is $25,000, with the full cost of many top schools topping $60,000. The knee-jerk response of the higher education industry is to point out that such gobsmacking figures only represent full-freight sticker prices, which not all students pay. But historically, they’ve provided little good data to back up that defense. In other words, we had to take their word for it.

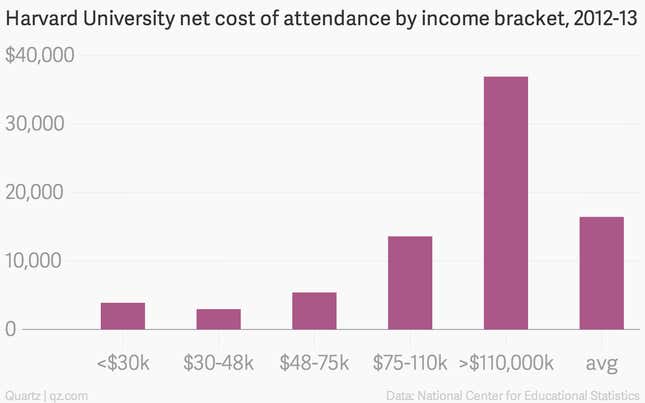

Until recently, that is. For the past several years, colleges have been required by the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 to report data on the true cost of attendance for students in different income brackets, after financial aid. This should be good news. It means that for every school in the country, we can make a chart like this one that looks at reported data from Harvard in 2012-13, the latest year available:

While this additional information might be better than nothing—students of modest means can see they likely won’t pay full tuition—I’d still argue that these numbers aren’t worth much.

Here’s why. Look at the chart. Notice anything screwy? According to the data, Harvard students whose families made less than $30,000 per year paid an average of $3,897 total, while students whose families paid between $30,000 and $48,000 per year actually paid less: $2,977 per year, on average. How could this be?

The 2008 law suffers from a fatal flaw that became clear when Wellesley College economist Phillip Levine dug into the data. The US government places students into income brackets differently than do many American colleges—they don’t require individuals who make less than $50,000 annually to report their assets. That means that some wealthy families who have many assets but no income—due to retirement, for example—are placed in the lowest income bracket by the government, even though students from those families likely pay nearly full price.

Not many students are misplaced in this way. But it doesn’t take much to confound the government’s data. As Levine points out in a November paper for the Brookings Institution, “Transparency in College Costs,” that’s because of a very foolish error that made its way into the law. The law makes colleges report the average cost by income bracket—a number that’s calculated by adding up the amount paid by each student, then dividing by the number of students.

But averages are easily skewed by a few large outliers. As Levine writes, “If the federal government simply required higher educational institutions to report median net prices by income category rather than average net prices, this would reduce the problems in the published data.”

For example, suppose nine students who appear in the lowest income bracket each pay $3,000 per year, but one student who was put there erroneously actually pays $50,000 per year. That’s enough to move the needle from an average cost of $3,000 per student to an average cost of $7,700 per student—an increase of over 150%.

This is a textbook case where reporting the median makes perfect sense: Most of the cost points are close together, with a few huge outliers that ought to be ignored.

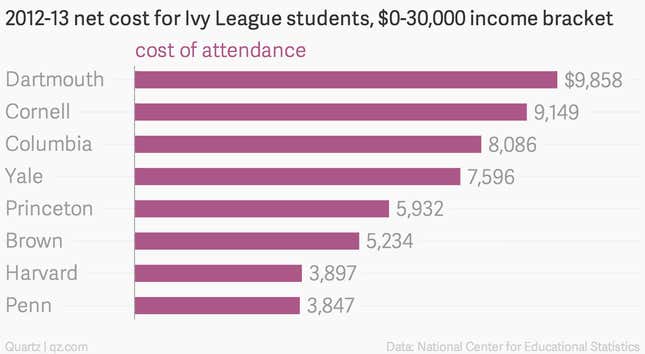

Using the mean instead distorts the data significantly. This is apparent when we look at the Ivy League. Though all these schools claim to cover all of undergraduate students’ demonstrated needs, their listed costs are all over the map. In the lowest income bracket, for instance, the cost of attending Dartmouth for one year appears to be nearly three times what it costs to attend the University of Pennsylvania, which is too large a spread to be believed. As Levine writes, these numbers “fail the sniff test.'”

So how much should a low-income student actually expect to pay? Unfortunately, we still don’t really know.

This shouldn’t be a difficult problem to solve. All it takes is a minuscule change in policy to ask for the median costs instead of the mean. Will that change happen? It’s unclear. A Department of Education spokesperson said that the DOE was aware of the distinction, but was not in a position to speculate on the decisions of Congress, which specified how the data should be reported in the 2008 Higher Education Act.

But the change hasn’t been made, which means students who use the government’s data will be misled. It also means that the difference between medians and means—a subtle statistical difference that most of us probably learned about in grade school—has rendered a big chunk of information practically useless to the very people who need it the most.