In 1989, I was a conservation student at the Courtauld Institute in London. During a class on varnish removal, my professor, Gerry Hedley, demonstrated how shining blue light on a picture with yellowed varnish made it seem as if the varnish had been cleaned away—returning the painting to how it originally had appeared. The demonstration in the classroom was jury-rigged—with a slide projector as the light source and a hand-held blue gel as a filter—but it was successful enough to convince me that one day, projected light could be used to restore the appearance of a painting without actually touching the surface.

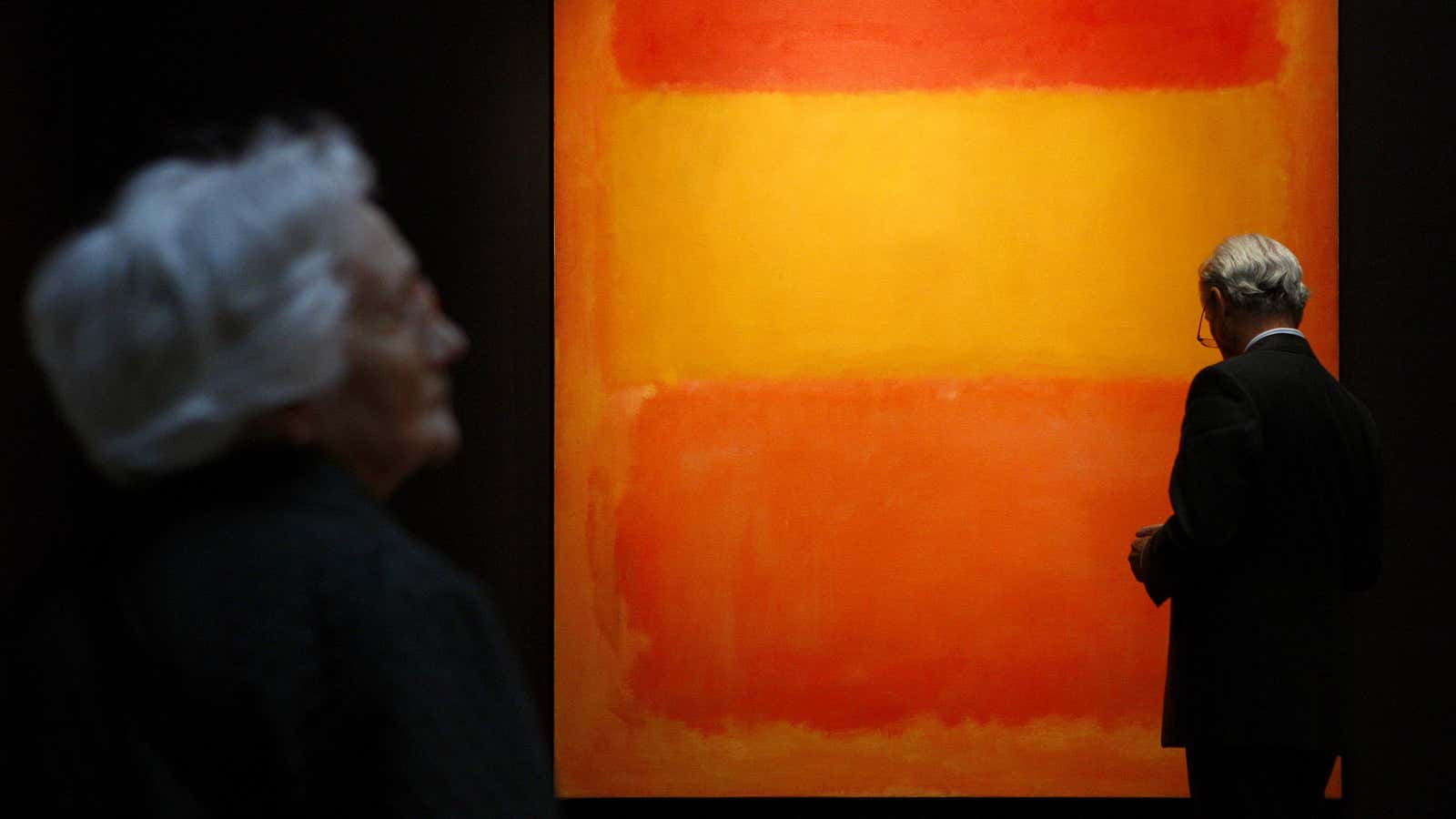

Mark Rothko is one of the preeminent abstract expressionist artists of post-war America. He painted only three mural commissions during his career: the Seagram Murals, now dispersed among Tate Modern, the National Gallery of Art and Japan’s Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art; the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas; and the Harvard Murals in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Harvard Murals, painted in the early 1960s, were originally installed in a penthouse of the university’s Holyoke Center in 1964. But the colors of the murals soon faded from exposure to direct sunlight, and each of the paintings faded in its own distinct way. A once-coherent collection had become disparate.

The university removed them from display in 1979. They have been rarely exhibited since.

Six years ago, the Renzo Piano Building Workshop began its renovation of the Harvard Art Museums, an ambitious project that combined the Fogg Museum, the Busch-Reisinger Museum and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum into one building. Meanwhile, the Harvard Art Museums sought to conduct an analysis of the Rothko murals to understand better their materials, study Rothko’s techniques, and, eventually, restore and display them in time for the opening on November 16th, 2014.

A team from the Harvard Art Museums spearheaded the restoration process: Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, who restored Rothko’s paintings in the Houston Chapel; Mary Schneider Enriquez, the curator of the exhibition; Jens Stenger, a physicist and artist now at Yale; art historian Christina Rosenberger; and me, an organic chemist and paintings conservator. Each of us brought a unique perspective to the vision of this complex project.

In the past, strategies for restoring paintings have included physically retouching over a varnish that isolates the restoration from the original. However, the delicate, unvarnished surface of the Rothko murals precluded the use of these traditional restoration treatments. Not only would retouching the paintings have been an irreversible process, but it also would have covered much of the artist’s brushwork. Knowing that we were not able to physically alter the paintings, we decided to use light to “restore” the lost color.

The first step was determining what the paintings looked like when they were installed in 1964. We had Ektachromes (color Kodak transparencies) of the paintings from the 1960s, but these, like the murals, had also faded. With aid from the University of Basel’s Rudolf Gschwind—an expert in restoring historic color photographs—we restored the transparencies to their original colors. Additionally, we used color measurements from an uninstalled painting, Panel Six, which belongs to Rothko’s children, Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko, and had retained unfaded sections. This gave us the target image, the closest to what the paintings looked like in 1964.

Next, we photographed the paintings in their current state and, using custom written algorithms, compared them to the target image. This allowed the camera, computer and projector to transfer information through their interrelated red, green and blue channels to produce a compensation image—what can be thought of as a “map” of the lost color.

Finally, using the camera and a software algorithm, we aligned the compensation image, before projecting the corrective colors onto the corresponding location, at the precise intensity—for over two million pixels per painting.

We worked through new challenges each step of the way. The use of this type of projected compensation system had not been used on paintings before, so we had to learn and improvise on the fly (and credit ought to be shared with the the MIT Media Lab’s Camera Culture group, who were wonderful partners). Jens Stenger also painted a 1:3 scale copy of one of the murals using the same pigments that Rothko had used for the originals. Throughout the process, we used the scale copy as a test piece, experimenting on it in lieu of the original works.

In the museum space, ambient light was an important complement to the paintings, and we used shutters on the ceiling lights to illuminate the floors and walls right up to the edge of the paintings. We also deployed low levels of overall illumination to bring the room together visually.

We chose a wall color that mimicked the olive-mustard fabric used by Rothko in the original installation. Two of the Harvard conservators who helped Rothko stretch and hang the paintings in 1964 were interviewed and independently provided confirmation of the color. The size of the room is close to the original in the Holyoke Center, and importantly the niche where the triptych hangs fits as tightly as the original.

This new projection technique can be used in the future to restore other paintings, and its effectiveness isn’t restricted to color field paintings; it could be used on any painting that has faded, whose original colors can be determined.

We hope the exhibition allows the viewer to experience the installation in its intended form, as a coherent whole—or, as Rothko described it: “…an image for a public place.”

Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals, along with the majority of associated studies, are on display until July 16, 2015 at the Harvard Art Museums.