When it came to matching words with deeds on the topic of racial equality, the most stalwart leader of the Western hemisphere, over the course of the 20th century, was Fidel Castro.

I say this as a black American who came to bond closely with Latin America as an adult, living in Mexico for almost two years, traveling and staying with families in the Dominican Republic, and making more than half a dozen visits to Cuba, where I strolled through its enchanting cities and drove into the far reaches of the countryside, forging relationships with its people, especially those of darker hue.

Now we are again feeling the heat of the burning topic, the man, who bonded black Americans to his Caribbean island. Yes, it was Fidel Castro who—even though out of power now for years—is angering so many Americans, especially police officers, over his signature action three decades ago.

It was Fidel who gave amnesty to Joanne Chesimard, known now as Assata Shakur, still wanted in the 1973 killing of a New Jersey state trooper, Werner Foerster, in a highway shootout. Shakur was convicted but was busted out of prison in 1979 by comrades. As a leading figure in the Black Liberation Army, which took bolder actions than even the Black Panther Party did, not only getting into gun fights with cops but holding up banks, Shakur became a legend in her time, a Robin Hood of the black masses.

On Dec. 17, in an historical moment, President Barack Obama announced he would seek to normalize relations with Cuba. On the same day, federal and New Jersey police officials repeated their offer of $2 million for information leading to the capture of Shakur. Last year the feds made Shakur the only woman on the FBI Most Wanted Persons list.

You can be sure on black websites and newspapers there will be attention given to the increasing calls for Shakur’s capture or negotiated return. That attention will come with a history.

Castro did not just provide a haven for fugitive revolutionaries, who made the argument, accepted by perhaps a majority of Cubans under Fidel Castro, that blacks were an oppressed people fighting for fair treatment and an end to police abuses in their communities.

No, he was a kind of Martin Luther King with power. For example, before the Cuban revolutionaries led by Castro took over Cuba in 1959, there was fairly rigid racial segregation through the country, including, for example, Santa Clara in the interior of Cuba.

When I was in Santa Clara in early 2001, a woman there told me how black and white Cubans in the 1950s and earlier had walked along different paths around the beautiful downtown Vidal Park. (All it took in Cuba to be white was to have straight hair, be fair complexioned and not want to be called “negro.”)

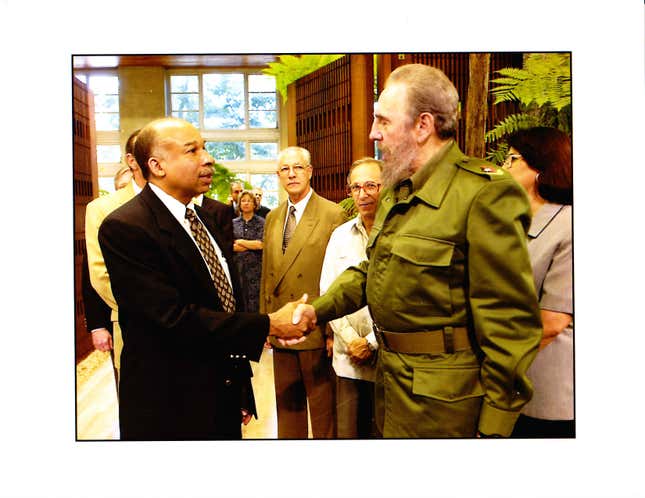

This racial division largely ended under the government of Fidel Castro. Moreover, Castro made an effort to reach out to blacks in the US.

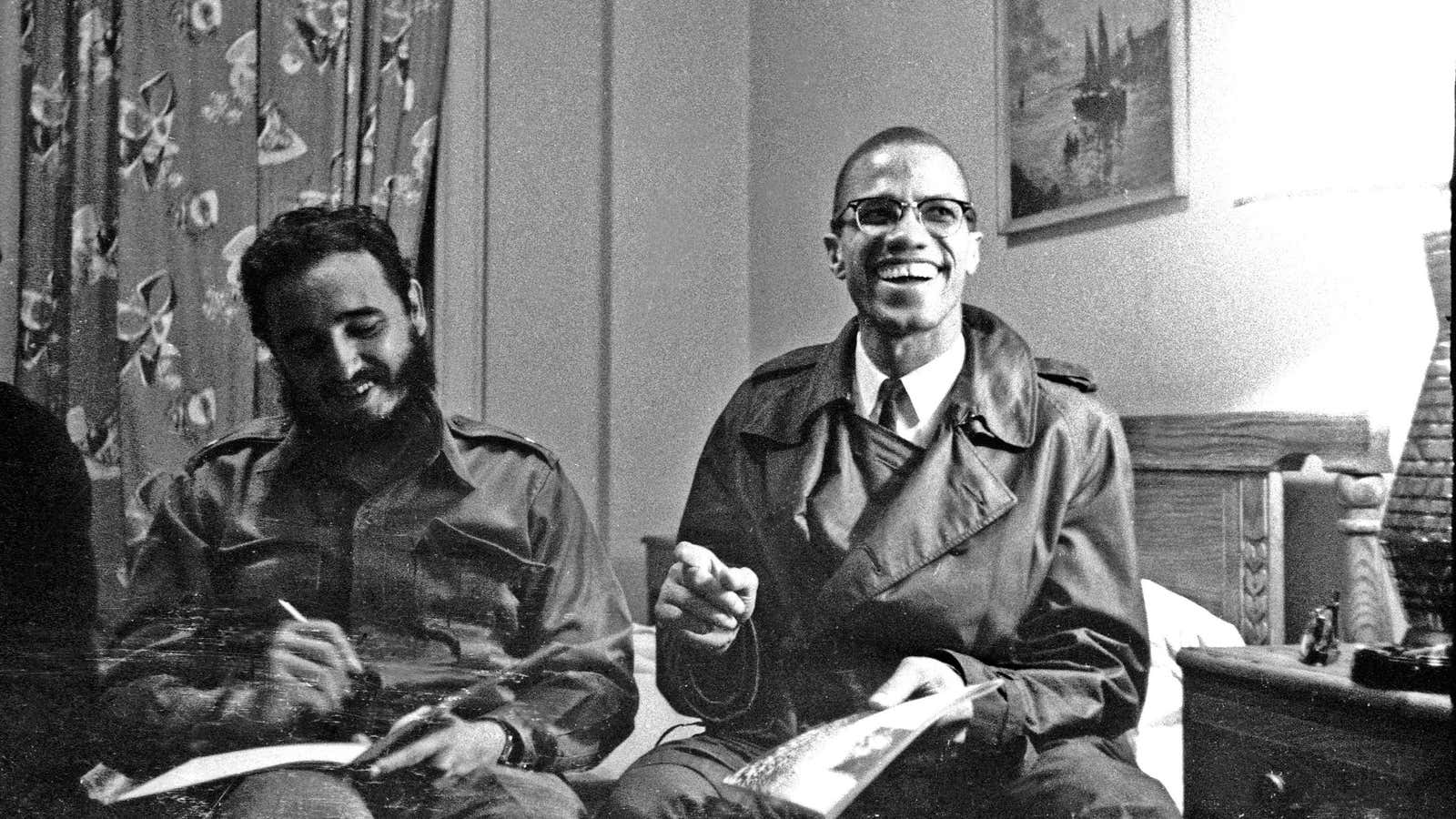

When he came to New York in 1960 for a United Nations meeting, Castro got upset at the management of the hotel where he was staying, the Shelburne, and he packed his bags and took his entourage up to the Theresa Hotel in Harlem, where he famously leaned out of the window and waved to the black residents of the community. Thousands of Harlemites called out his name in a bonding-with-power they were totally unaccustomed to.

And it didn’t stop there.

In the 1980s, before the end of the Cold War, Fidel sent some 25,000 troops to fight in Angola, on the side of those opposing the then-apartheid government of South Africa. This aspect of Castro’s time in power was little reported in the US media. Fidel militantly opposed racist South Africa at a time when the US was diplomatically supporting it.

It was I who in 1987 first reported that Shakur had actually escaped to Cuba and was residing there, protected by Castro. I spent several days with Shakur at her apartment and walking along the Malecón; my Newsday colleague, photographer Ozier Muhammad, photographed her as she posed provocatively outside the US Interests Section, hands up in victory.

As you know, things have changed since then.

The Soviets stopped supporting Cuba; and then the Soviet Union collapsed to the ground. For two decades there has been speculation that one day a liberal American president might move to end the now-half-century embargo against trade with Cuba and allow Americans to travel there freely.

Republicans and many Democrats were outraged at what they called a concession by Obama to the communism they said Cuba—through the retired Fidel’s brother Raul—still represents.

Muffled in the discussion on cable channels are the feelings of kinship and appreciation that black Americans hold for Fidel Castro.

Many of those who harbor such tenderness toward the bearded one do not shout it into microphones because they don’t wish to be accused of being anti-American. But sympathy with Fidel can be seen in decades of blacks voting in Congress. Harlem’s Congressman Charles Rangel, for instance, has been among the most progressive of all representatives when it has come to policies toward Cuba, over the year having proposed an easing of the embargo. And few on the national scene have been more militant in opposing the embargo than black California Congresswoman Maxine Waters.

In the coming days, Assata Shakur will be mentioned more frequently in news stories about Cuba, especially in the northeast. There are growing demands that the United States find a way to bring her back and to put her in jail. And in their stories, New Jersey newspapers are noting how Assata Shakur is being treated as a heroine by many in the black communities of America.

Federal officials and others are aware of how Shakur has become a kind of folk hero among black Americans and even blacks in the Caribbean, with a number of parents over the past 25 years naming their daughters Assata.

Adding to the appeal for blacks is Assata Shakur’s connection to the late rapper Tupac Shakur, who is related to Assata through his male ancestors (though not by blood) and is considered a nephew.

When I wrote about Tupac Shakur for a now defunct black weekly newspaper (the City Sun) I spoke with a top New York federal official, Ken Walton, who said Assata Shakur damn well better be careful of her every move—then, in 1996, and for the rest of her beating-heart life.

I wrote then of Walton “He told me in measured, angry words that he ‘or somebody like me’ will one day capture Assata and bring her back to the States.”

This I know to be true: Every time a fist was raised for Assata Shakur, sympathy was expressed also for the now old Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

By the way, Assata is not the only revolutionary received by Fidel with open arms. He also gave asylum to Nehanda Obiodun (formerly Cheri Laverne Dalton), the only person still wanted in the early 1981 $1.5 million Brinks armored vehicle holdup in Nanuet, New York, in which two police officers were killed.

These days it is not easy to find out where Assata Shakur and Nehanda Obiodun are or even what they are thinking. I hung out with Obiodun and wrote about her in Cuba in the 1990s, but I was blocked at every turn when I tried to get her and Shakur to meet with me and a group of Stony Brook University students I took to Cuba in January of 2012.

Obiodun has been almost completely off the radar in recent years, out of mind. But Assata Shakur has not been. “New Jersey hopes Cuba-US relations thaw will help extradite former Black Panther,” screamed a headline of Atlantic City News on Dec. 18.

And so, given all this as background, black Americans are not only reflecting nostalgically on Fidel Castro, they are concerned about the plight of Assata Shakur.

Some, perhaps many, black police officials publicly declare their desire that Shakur be captured and returned to jail in the US. But other blacks have respect for the courage she showed as she lived in exile for some 30 years, bearing in her torso the remnants of a bullet she took during that shootout in 1973.

Most of all, you can bet, there is a broad agreement with Barack Obama—that the time for hostility with the Cuban government—no longer headed by Fidel Castro but largely by his brother Raul—should be over.