The Apple Watch—set to launch in early 2015—is already having a dramatic impact on the watch industry, where executives are now rushing to figure out their smart watch strategy.

Credit Suisse published a lengthy, in-depth report on the Swiss watch industry (pdf) in October 2013—well before Apple’s project was unveiled, but early enough that smart watches and fitness bands were coming into the picture. While some of the facts and figures aren’t the most recent, they’re useful as background about an age-old industry that is about to experience an entirely new form of competition. Here are some key points to keep in mind:

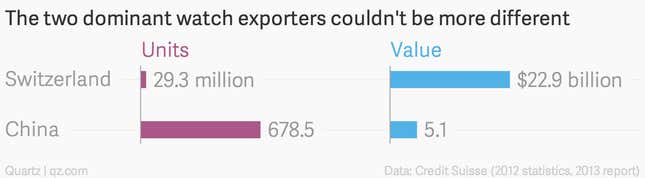

1. The global watch industry is dominated by few countries, mainly Switzerland and China.

About 1.2 billion watches are produced annually, according to the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry’s estimates (pdf).

China is the world’s top watch producer in terms of unit volume, but 99% are inexpensive, quartz watches. In the luxury segment, Credit Suisse’s analysts write, “Switzerland enjoys a near-monopoly position.” About 95% of that production is exported. Hong Kong also plays a role as a shipping and re-exporting hub, including to mainland China.

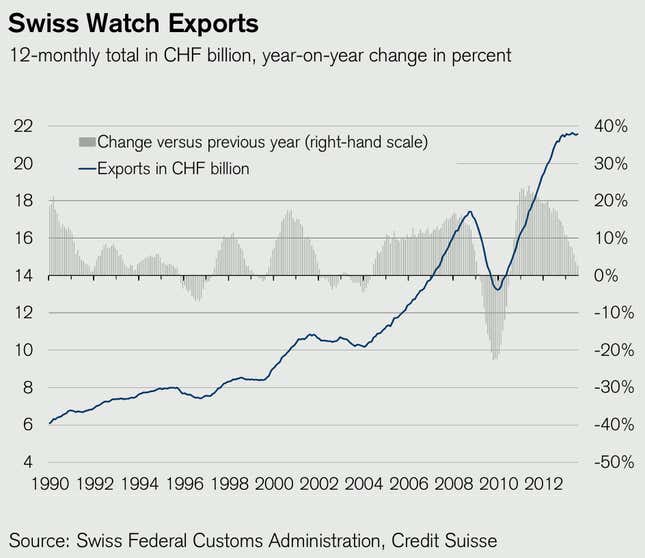

2. The Swiss watch industry, “pronounced dead” in the 1970s, eventually made a huge comeback.

The Swiss re-focused on high-end watches just as global demand for luxury goods started rising in the mid-1990s. While exports dipped during the most recent recession, a boom followed.

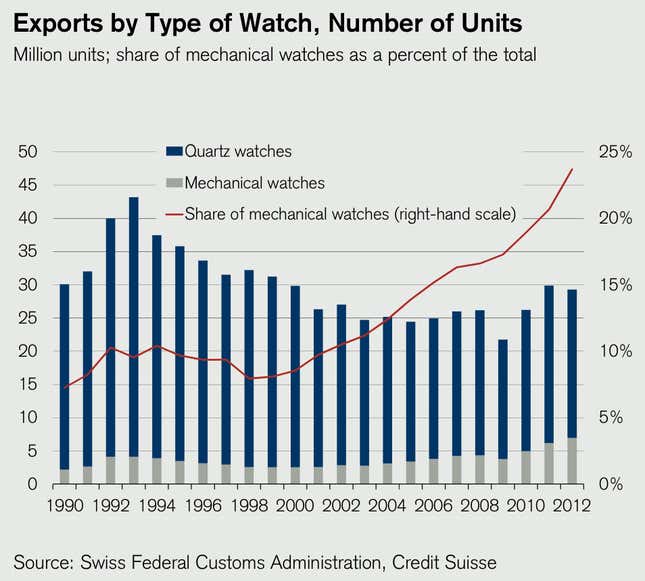

While expensive, mechanical watches are growing in popularity, Swiss companies still make a lot of cheaper, quartz-based watches. This keeps the industry diversified, gets the “made in Switzerland” brand more exposure, and generates the production volume that’s necessary for some economies of scale.

3. Chinese consumers fueled the Swiss watch industry’s recent boom—unsustainably.

As China grew as a luxury market, the value of Swiss watch exports to China increased by a factor of almost 100, from 16.8 million Swiss francs in 2000 to 1.6 billion in 2012. Chinese tourists also helped—in 2012, some 37% purchased a watch while traveling overseas, according to a 2013 KPMG report on China’s luxury market (pdf).

Then Swiss exports to China “began to fall abruptly in the middle of 2012,” before stabilizing. According to Credit Suisse, reasons “include anti-corruption measures, restrictions on advertising, as well as slower economic growth in China.”

4. The Swiss watch industry is dominated by a handful of vertically integrated conglomerates.

The majors: Swatch Group (brands include Swatch, Omega, Harry Winston, and Tissot), Richemont (Montblanc, Piaget, Cartier, Alfred Dunhill), LVMH (Tag Heuer, Hublot, Zenith), and Rolex (Rolex and Tudor).

In a push to vertically integrate, brands have been “buying up suppliers across the board, or are building up their own production capacity,” the report notes. This extends from the most essential watch components—hands, dials, wristlets, movements, and cases—to distribution and retail outlets, which the conglomerates own or license around the world.

5. A watch is only considered “Swiss made” under very specific conditions.

The watch’s movement must be Swiss—assembled, cased up, and inspected in Switzerland, with at least 50% Swiss components (by value). A more recent “Swissness” amendment requires that “at least 60% of the product’s manufacturing costs must have been generated in Switzerland” and “the activity that gives a product its essential characteristics must take place in Switzerland.”

6. The Swiss watch industry probably isn’t doomed—yet.

Credit Suisse concludes—or, at least it did a year ago—that its local watch industry should be mostly fine, with growth expected from markets like Vietnam, India, Russia, Ukraine, Malaysia, South Korea, and Mexico. “The taste for Western status symbols in the emerging markets is likely to remain high, and in contrast to other luxury goods, such as automobiles or artwork, a watch can be worn and displayed at all times,” according to the report. “Moreover, a watch is the only universally accepted piece of jewelry for men.”

But what about smart watches like the Apple Watch, which is essentially a wrist-top computer? These aren’t mentioned—again, the Apple Watch didn’t exist yet—but as the report notes, “the watch’s function as a timepiece is less relevant in the era of mobile phones and computers. For the owner, it is more of a social signal, communicating the wearer’s external values such as status or personality.”

Our view: Providing this “social signal” has long been Apple’s strong suit, especially relative to other consumer electronics companies. There is, however, a timelessness to luxury watches that Apple will need an answer to. In the era of the almost-throwaway iPhone, which people replace every couple of years, it’s hard to imagine an Apple gadget as a family heirloom. But with real thought put into materials and style, and strengths in marketing and distribution, Apple could provide the Swiss watch industry some genuine competition in 2015.