As midnight approached on Dec. 11, a circle of Zappos and Downtown Project employees lifted up their shot glasses around a bonfire near the edge of the Fremont East District in downtown Las Vegas, where Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh is conducting one of his many social experiments. He calls the private area, filled with about 30 Airstream and Tumbleweed trailer homes, an attempt to create an urban version of the Burning Man festival.

The circle around the bonfire (situated in front of Hsieh’s trailer) included members of his inner circle—downtown resident Ranielle Rivera and Zappos buyers Kristin Colbert and Lauren Randall. The group ebbed and flowed, breaking into smaller circles as it moved to different venues in downtown Las Vegas, many of which Hsieh had personally funded through Downtown Project, and converged at the park just before the stroke of midnight, when Hsieh would begin celebrating his 41st birthday. (Downtown Project is his personal investment in the area surrounding the new Zappos corporate campus, and includes real estate, small businesses, and tech startups.)

Hsieh is attempting to create an entrepreneurial utopia that revolves around Zappos, the e-commerce site he helped build in 1999 and has recently relocated from suburban Nevada to the old Las Vegas City Hall. As part of his extreme experimentation with civic and business organization, Hsieh is also delivering a shock to the company’s internal operations by replacing the traditional management structure with a new system called Holacracy, as Quartz has reported.

“We want Zappos to function more like a city and less like a top-down bureaucratic organization,” Hsieh tells Quartz, saying that when cities double in size they become 15% more productive, but when companies double in size, productivity declines. “Look at companies that existed 50 years ago in the Fortune 500—most don’t exist today. Companies tend to die and cities don’t.”

Hsieh’s experiments with corporate organization make Zappos an important laboratory for confronting some of the plagues of large companies, including employee disenchantment and inability to take risks, move quickly, surface problems, and tap into the full staff’s best ideas. A wave of other companies, many of them tech startups, are similarly trying to reengineer management practices.

Since moving from San Francisco to Las Vegas in 2004, Zappos has struggled with attracting engineering talent. More recently the company experienced what some call a tech exodus—bleeding talent to San Francisco and Silicon Valley firms—and is taking seriously its need to attract top-level engineers if it’s going to stay ahead of the curve in e-commerce. The new internal structure, in conjunction with the Downtown Project, is a bet to move Zappos into the next chapter, pushing it to innovate beyond shoes, beyond online retail—to become more of an all-encompassing brand like its parent company Amazon.

Hsieh is using Holacracy to push his 1,500 employees to operate more like entrepreneurs. Over the past year and a half, he’s stripped all Zappos employees of their titles, at least internally, and is doing away with traditional managers. Through a process called badging, all employees will now have to prove their skills if they want to continue performing certain functions within the company, whether they’ve been around for two months or 10 years. He’s restructuring the company to work more along the principles of an open market—with real-time supply and demand—than a traditional hierarchy and wants his call center, the bread and butter of the company, to operate more like the car-service startup Uber.

“An Uber driver doesn’t have a shift. They can decide to show up or not show up,” he says. “We want to apply that same thing to incoming phone calls. Holacracy, open market, badging—all are going to be a huge part of it. You need all those things to work together. It’s a long process, and we’re still learning. Ninety-nine percent of the company doesn’t know or see the behind-the-scenes work.”

But reengineering Zappos to operate more nimbly has not come without friction, and has likely made it significantly harder to recruit and retain the top technical talent Zappos needs. Many of its employees are frustrated with the new internal structure. Some have left the company because of it. Along with the move to downtown Vegas and a drawn-out migration to Amazon’s SuperCloud technical infrastructure—which many say is the foremost reason for the tech staff departures—Zappos is going through one of the most tumultuous years in the history of the company.

Relinquishing power

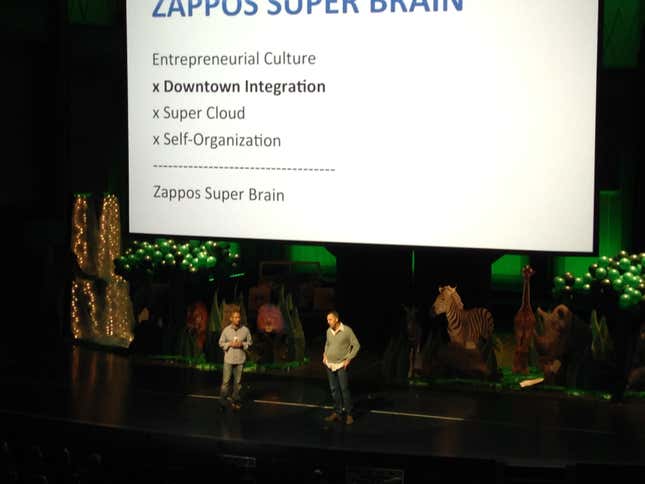

At Zappos’ fourth-quarter all-hands meeting in November 2013, human resources head Hollie Delaney stood on stage between Hsieh and longtime executive Fred Mossler with tears in her eyes as she shared her experience using Holacracy. She said she had learned to relinquish power, and as a result, encountered breakthroughs in her relationships with colleagues. For the first time, she and her coworkers were able to “process tensions” in a healthy way. “People would always look to me: ‘Is it OK that I do this?'” Delaney told Quartz last month. ”All the sudden, I saw people break down, fear broken down.”

The auditorium filled with Zappos employees—dressed up in animal costumes in the spirit of the meeting’s theme, “Gone Wild”—fell silent. Some had already begun the process of re-defining their responsibilities and engaging in “tactical” and “governance” meetings as outlined by the Holacracy Constitution. Others were being prepped for the migration to this new management system in 2014.

Holacracy is a trademarked system, developed by software engineer Brian Robertson, that’s in many ways a tool to get companies to operate more like software. Robertson uses engineering terminology and likens Holacracy to Apple’s iOS operating system. The system, largely misunderstood as non-hierarchical or flat, actually creates a new hierarchy around work rather than titles.

The term Holacracy is derived from the Greek word holos, which means a whole that’s part of a greater whole. In a Holacratic organization, the company is divided into a collection of circles that are encompassed by the largest internal circle (called the “General Company Circle,” or GCC) and then the board of directors. The system is designed so that circles can be created and disbanded at any time. The vision is for employees to hold multiple roles and move fluidly throughout circles, making it easier to efficiently and frequently reorganize the company. Publishing platform Medium, training and consulting firm David Allen Company, and strategy consultancy UnderCurrent are a few notable companies that have adopted Holacracy.

Zappos is the largest company to experiment with the system. The online retailer began by moving its HR and recruiting teams to the new system in early 2013, and now approximately 80% of the company is organized into 250 different circles. A much smaller percentage is actively engaged in practicing Holacracy.

At a HolacracyOne training session last year, employees tried to wrap their heads around the new structure, along with its complicated verbiage. One afternoon they debated how to integrate the Zappos culture into a system that many say can feel robotic.

“At Zappos there’s so much implicit stuff you’re supposed to do because it’s part of the culture,” said a young woman wearing a grey hoodie sitting at a circular table with Zappos and Downtown Project employees. “But where do we put it?”

“Our team does the parades,” a Zappos recruiter chimed in. “But what if some of us don’t do parades? Is it a domain, role, policy?” (Within Holacracy, roles and accountabilities are more narrowly defined, whereas a domain can encompass multiple roles. A policy grants or limits authority within a domain.)

“Policy is really hard because the definition of a normal policy has nothing to do with what we have going on here,” the young woman responded.

Hsieh jumped in: “In general, have a bias against domains.”

“You want to leave people as much freedom as you can,” added Robertson. “If you really need a domain, use it. Be careful with it—it’s a big hammer.”

Jamie Naughton, whose external title is chief of staff, says that “in the beginning, you feel that the human element is lost completely. I remember sitting in meetings wanting to scream at the founder of Holacracy, ‘You don’t get it, you don’t get it at all!’ He said, ‘You’ve got to trust the process.’ And I thought, ‘This sucks.’ You just have to wait your turn to speak your opinion.”

Although the system is designed to more evenly distribute power, it’s difficult to ignore longstanding power structures. Many managers are now lead links of circles, tasked with guiding meetings and workflow. But under Holacracy they technically can’t tell employees how to complete that work.

Hsieh says that the responsibilities that used to be held by managers are now split between three roles: lead link, #mentor, and compensation appraiser. (In a tech-y conceit, the #mentor role does actually have a number sign in its name.) The #mentor circle is exactly as it sounds: matching employees with mentors. While lead links are focused on guiding the work itself, mentors are tasked with employee growth and development, and compensation appraisers work with both to determine an employee’s salary. “Manager” is now essentially barred from the Zappos vocabulary; but in casual conversation, employees still use the term.

“The hardest part is operating in two worlds right now,” says Hsieh, who currently sits in 16 circles and holds a few dozen roles including lead link of the “experiential SWAT team” and “contribution appraiser.” He and others explain that becoming familiar with the Holacracy Constitution is like learning the rules of poker, football, or any game. The next step is entering the arena.

“Now they have the basics of the rules,” Alexis Gonzales-Black, a Zappos recruiter who is co-leading the transition, tells Quartz. “2014 was about the scalability of getting the nuts and bolts, the meetings, the circles, the work captured [in the online system called GlassFrog]. 2015 is about the qualitative implementation of Holacracy.”

A bumpy ride

So far, the shift toward Holacracy has been a bumpy ride for Zappos. Reactions within Zappos to the staggered rollout have been mixed; there are pro- and anti-Holacracy camps throughout the company. Many see the system, criticized for being too rigid and dogmatic, as a hindrance to getting work done—especially when it comes to the structure of meetings, which are filled with protocols and don’t allow for small talk. The tech team, consumed with the move to Amazon’s SuperCloud infrastructure, hasn’t had as much time to shift to the new system. Perhaps not surprisingly, many in HR (or what was formerly called HR) are proponents of the system and its benefits. Most Zappos staff, however, are in the midst of the difficult transition that employees refer to as “the dip.”

HolacracyOne, the consultancy that works with companies to implement the system, provides a basic framework but has left big questions unanswered, like compensation and hiring/firing. Some employees have shared with Quartz that they feel they now have more roles for the same pay.

“How do you compensate someone who’s on the phones 50% of time, works 20% in wellness, and 20% in a merchandising role with product?” says Delaney, who is now the lead link of the company’s senior HR circle, called People Ops. “There’s no market-based compensation for that person. Right now we’re trying to figure out what is that world going to look like, and how do we fairly compensate people in that system?”

Zappos has created a compensation appraisal department that is now doing an audit of all salaries and pay grades. The company is known for its zany culture and employee benefits, but not for generous salaries. Call center employees start at $11/hour and are paid $13/hour once they hit the floor. Many current and former tech employees say that their salaries aren’t competitive enough, especially in a current marketplace with high-value startup valuations and lucrative job offers just across the border in California. (The salary-tracking site Glassdoor identifies a snapshot of Zappos developer positions as running somewhere between mid- to below-average market rate.)

The call center, which has around 500 employees (one-third of the company), is currently in “the dip” with Holacracy. Gonzales-Black describes that phase as the difficult shift in mindset. Over time, it’s important that this group engages with the new system well, since it’s on the front line of a company whose reputation relies on customer service. Hsieh’s vision for Zappos’ call center operating like on-demand car service Uber will only work if he gets employees’ buy-in.

“Holacracy has surfaced lots of longstanding tensions,” says Gonzales-Black. “We’re engaging a lot more difficult conversations.” Traditional power dynamics are readily apparent in the call center (its Customer Loyalty Team, or CLT), where supervisors have long called the shots as entry-level employees stay focused on answering phones. Although CLT employees are encouraged to take liberties with customer service, the division has always been clear. Holacracy is ostensibly an attempt to change that—or, at least, provide a veil of empowerment (or some combination of the two). No matter, if it changes how employees view themselves in relation to their work and their colleagues, Hsieh will have succeeded.

Asking employees to air their grievances more regularly and honestly at a company where happiness is expected is a necessary risk as well. “When you have a culture that values so much of people’s quirkiness and emotional state and outwardly being kind, cheerful, generous, and happy, sometimes you can make it seem like it’s not OK—even in a very subtle way—to not be happy all the time,” Owen Carver, a former Zappos employee, tells Quartz.

Carver worked for the company’s call center in San Francisco and moved with Zappos to Las Vegas in 2004. He says that in the early days, the division of power was very clear between those who answered phones and the supervisors.

Grievances were processed behind closed doors. He says that call center employees were rarely asked for their feedback, so once he decided to express concerns about the company’s management structure through one of its online customer service forms meant to be used by customers. “I took advantage of the return order system,” he says, “which asked, ‘How can Zappos do a better job?’ I had never been asked that question before.”

While that led to some honest discussions about management, many difficult conversations never took place, says Carver. He recalls Hsieh leaving a copy of the book The Right To Protest on his desk, but Hsieh, known for his hands-off management style, didn’t take the opportunity to start a dialogue. (Hsieh says that he doesn’t remember the incident and adds that the call center is now led by a different team.)

Holacracy is intended to bring some of those honest discussions to the forefront. “Maybe [CLT team members] weren’t comfortable expressing those voices before out of fear of being shut down,” Brironni Alex, a former manager who now leads one of the CLT phone circles, tells Quartz. “It’s one of the things we kind of struggle with within the company: relinquishing power and overstepping boundaries. Holacracy makes it easier to call people out and say, ‘What role are you filling right now?’ It’s a system of checks and balances.”

This all raises some fundamental questions: Is this scale of change necessary for a company that already brings in a few billion dollars in revenue annually? (Amazon does not release Zappos’ financial information.) And how much is all of the focus on implementing Holacracy a distraction from the growth of the business itself?

“Things are going to get slower before they get faster,” John Bunch, a software engineer who is leading the transition along with Gonzales-Black, tells Quartz. “There are pockets of strong practice.” Both speak about the power of leveraging Holacracy once the company gets fully up and running. They also acknowledge that the system won’t work for everyone. And like Hsieh, they channel the vision that Holacracy is ultimately about increased adaptability.

“Every Zapponian has to decide,” says Bunch. “Is this a company and an organization that I want to follow along that journey?”

And not every Zappos employee is willing to make the transition. Recent departures since the rollout include David Hannigan, who was brought in as the chief information security officer after the company’s data breach in 2012; Larry Hernandez, a recruiting lead who was in the pilot group for Holacracy; and former CTO Arun Rajan who was part of the tech exodus. Rajan returned this fall as interim COO and says that he now understands the inner workings of the company better since everyone’s roles are more clearly identified. “It’s the best tool we have to move into self organization,” he tells Quartz.

In many cases, Holacracy served as the tipping point for departures. Some former Zappos employees say the system makes it hard to hold staff accountable for meeting deadlines, and get people to take responsibility for things that need to be done. But “for a lot of us who left, Holacracy wasn’t the No. 1 reason,” says a former employee who held a senior role in the company and asked not to be named. “The No. 1 reason is that people don’t understand the strategy for Zappos. What’s the strategy? Part of the strategy is self-organization.”

Groupthink and weak links

Harvard management professor Ethan Bernstein, who has studied Zappos and other companies that are pursuing new modes of organization, tells Quartz that Holacracy isn’t the answer to becoming self-managing. Ultimately, it’s not about whether Holacracy is the answer but instead what problem you’re trying to solve. Holacracy’s biggest value, in Bernstein’s view, is that it provides a framework for effective conflict resolution: “Holacracy replaces that [traditional] structure with a structuring process, at least for particularly frequent kinds of conflicts, to resolve conflicts in a potentially less-hierarchical, more self-organized, and more adaptive fashion.”

Hsieh and other Zappos executives echo Bernstein’s sentiment, and explain that Holacracy is, for now, a catalyst but may not be the long-term solution in moving toward self-organization. “There’s no end date,” says Mossler, who has been with Zappos since the very beginning. “We’ll stay with it as long as it’s the best system.”

The system has many points of apparent contradiction: while it’s intended to hand control to employees, Holacracy’s ratifier (in this case, Hsieh) maintains the power to disable it at any time. And while staff are encouraged to process tensions and share the floor, they are forced to do so using a specific language. Asking employees to all speak the same language in the name of giving them a voice raises a red flag. Does Holacracy ultimately push employees into groupthink?

Hsieh says groupthink is a risk but that it’s important to first get everyone on board with the system. “The first city grids didn’t have electricity,” he tells Quartz. “It’s not that version one is the end-all be all. … Another analogy is, if there are 100 people and they each speak a different language, none of them will be able to communicate with one another. English may not be the best language for everyone to speak. If you’re designing a language from the ground up it’s more logical to get people speaking the same language first and evolve it over time.”

But Hsieh isn’t trying to convince everyone; he expects a certain amount of turnover in the process. “That’s what happened when we rolled out our core values in 2004, 2005. Some people didn’t love that they could be fired for a values violation.” He adds that between Holacracy and SuperCloud, “not everyone will have the patience to wait.”

Delivering happiness

The experiment is being watched closely by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, according to Zappos executives. (Quartz reached out to Amazon for comment but did not hear back.) Hsieh spoke to Bezos about Holacracy and reports that he’s observing Zappos’ deployment of it with interest. This sort of freedom to experiment is something Hsieh fought for early on.

In his book, Delivering Happiness, Hsieh says that he never wanted to sell Zappos but that the company’s board—and, in particular, investor Sequoia Capital, the venture capital firm which kept it afloat with $48 million in the mid-2000s—was getting tired of his “social experiments” and wanted the company to improve profitability. Instead of risk getting forced out, Hsieh decided to sell the company to Amazon, which also values reinvestment over immediate bottom-line growth. Like Amazon, Zappos has long operated with razor-thin margins even as its revenue has grown exponentially. Alfred Lin, Zappos’ former chairman, CFO and COO, says of Hsieh: ”I’ve never seen someone operate so close to zero in my life.” Lin left shortly after the Amazon sale in 2009 and is now a partner at Sequoia.

Hsieh, who says that Zappos will be highly profitable over the long term, is taking full advantage of a parent company that so far has tolerated his social experiments, and taken on some core areas of the Zappos business such as tech infrastructure and product fulfillment. With the sale, the companies informally agreed upon five tenets to guide their relationship, the first of which was Amazon’s promise to allow Zappos to operate independently. “It doesn’t matter if we’re doing all these experiments as long as we make our financial plan,” Hsieh tells Quartz. “Then they leave us alone.”

Hsieh has long shared his vision for making Zappos an all-encompassing customer service brand. For years, he’s even thrown around the idea of creating a Zappos airline (miniature Zappos airplanes sat on employees’ desks back at the old headquarters). With the move to Holacracy, there is now a circle devoted to exploring the airline concept. “Maybe we would have a couple Zappos employees focusing on the food and drinks, trying to emulate the glory days of Pan Am,” he says, “and let the airline [carrier] worry about safety. That’s just one idea we’re looking at.”

His fascination with self-organization goes back to the 1990s when he and Lin would discuss it at LinkExchange—the internet advertising network they built and sold to Microsoft for $265 million—as an ideal way to run a company without having to manage. In Delivering Happiness, which Hsieh finished writing just before closing with Amazon, he hints at rave culture contributing to his early fascination with self-managed systems, likening the synchronicity of crowds moving to a single beat.

Some critics charge that the shift to Holacracy is more about Zappos marketing itself as an innovative company than fundamentally changing how it is run. “If you look at the system, the lead link is really almost like a manager,” says the former senior-level employee. “There was a disconnect between what was being represented internally and externally. You can say all you want, but within Zappos, if you look deeper, the inner circle still dictates.”

At the very least, the company’s move to Holacracy is great publicity for Zappos. Hsieh, a gifted marketer who is lead link of the “Brand Aura and Storytelling” circle, often says that “a great brand is a story that never stops unfolding.” Telling the world that he’s relinquishing some level of power—no matter if it’s actual or perceived—and pushing employees to operate like entrepreneurs is enough to attract the kind of attention and some of the talent the company is looking for. It remains to be seen whether they’ll stick around long enough to buy into Hsieh’s social experiment and whatever comes next.

Feature image by Flickr user Malone & Company Photography (image has been cropped).