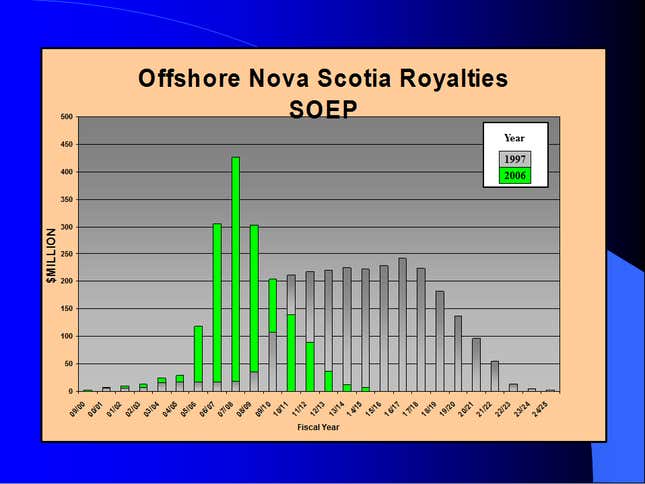

HALIFAX, Canada—In 2007, Sandy MacMullin was sitting across from his boss, a deputy minister in Nova Scotia, on Canada’s east coast. They had struck a windfall—enough natural gas royalties to pay $500 to every man, woman and child in the province, with cash to spare.

But MacMullin and all else in the room also knew what few outside it wanted to face: Such bonanzas were about to end. After a string of failures, the oil industry had declared the province dry. In just five years, gas production would begin to plunge, and soon after that there would be almost no royalties at all. Already deep in debt after the decline of the province’s lifeblood cod, lobster and timber businesses, Nova Scotia would be in trouble.

“I want a plan,” MacMullin’s boss said.

What followed was an extraordinary journey in which MacMullin, a burly native of the province with a broad grin and blow-dried hair, sought to prove the experts wrong. Nova Scotia’s salvation, he was convinced, lay in the same place it had been—its offshore oilfields. Although the old wells were declared to have dried up, there still had to be reserves in places people had overlooked.

Today, BP and Shell are embarked on a combined $2 billion in spending to explore Nova Scotia’s waters anew. What lured them back were the fruits of an exceptional geological treasure hunt, led by MacMullin, which yielded estimates of 8 billion barrels of oil offshore—four times the volume produced in all previous drilling in the province as a whole.

Nobody will know if MacMullin’s labors have paid off until later this year, when the first well is spudded. And now, with oil prices plunging and companies scaling back their exploration, it could all be at risk—although both companies say they are carrying on regardless for now. But if there is oil and it is economic to extract, it could stop Nova Scotia’s decline and transform this quiet, mannerly and relatively isolated province of 940,000 people into the scene of a roiling new oil boom.

To begin with, however, all MacMullin had to go on was a hunch. To back it up, he would have to persuade his bosses to spend $15 million from spartan provincial funds on specialists with an extremely arcane skill: paleogeology, the painstaking reconstruction of the long-ago world.

“We could have sat and waited for the demise, but no one wanted that,” MacMullin said over breakfast in this tawdry port. “We had to do something.”

The birthplace of the continents

Two hundred million years ago, a gigantic supercontinent, Pangaea, comprised all the land on Earth. Nova Scotia and Morocco, today separated by about 3,100 miles (5,000 km) of the Atlantic Ocean, were conjoined. And since oil had been found in the deep waters offshore from Morocco, MacMullin had heard from experts, it stood to reason, geologically speaking, that it must be present in Nova Scotia, too. The two were “analogs” of one another. By starting at the very birth of the conditions for the creation of hydrocarbons, they might locate Nova Scotia’s petroleum trove.

Sandy MacMullin is 55 years old, solid like the amateur hockey player he was for years, and a fitness fanatic, bicycling for 25 minutes every day to his office near the marina even in Halifax’s freezing winters. In college, he studied agricultural engineering, but he landed a trainee government job in oil reservoir analysis, and liked the work. Three decades later, he heads up Nova Scotia’s Petroleum Resources Branch, which makes him the government’s leading oilman.

In order to reverse the deeply held pessimism about Nova Scotia’s oil prospects, MacMullin had to demonstrate the potential for significant new discoveries. Given the dramatic industry exodus, it meant starting from scratch, and MacMullin did what politicians and bureaucrats typically recommend in a crisis—he commissioned a study.

He contracted it to a group of retired BP scientists at a UK firm called RPS. Leading them was a Cypriot-born geologist named Hamish Wilson. Examining Nova Scotian history, Wilson noticed that the early drillers had worked almost entirely in extremely shallow water—400-500 feet (120-150m) deep. He also observed that, in their post-1986 run of bad luck, they had been relying almost wholly on 1970s seismic methods—tools that are rudimentary by today’s standards.

It was possible, RPS said, that something had been missed. Wilson’s proposal included going deeper—hunting for an entirely new oil province in 6,500 feet of water, reaching for much older geology, and using much more advanced exploration tools. Wilson’s model would reconstruct Nova Scotia through eight geological eras going back to the early Jurassic age, just as Pangaea was breaking up. Given how oil cooked up over time, that was where, if substantial undiscovered reserves existed, they would be found.

Such “analog exploration” is a current geologic rage among international oil companies. Along much of the north-south strip of geology underlying the Atlantic Ocean, oil explorers are noting where petroleum has already been found, and then, in a nod to Pangaea, looking for its analog in a place to which it was once fused, often thousands of miles away on another continent.

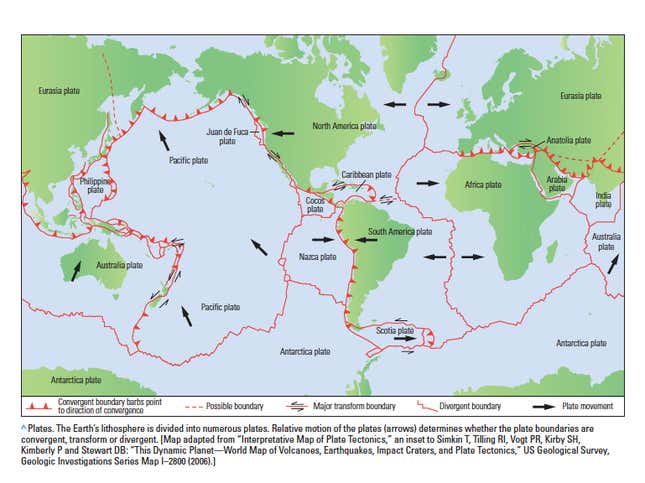

Pangaea is only the latest of numerous supercontinents in the earth’s history. At approximately 300-million- to 500-million-year intervals, for at least 3 billion years and perhaps longer, plate tectonics have created and broken up these land masses. Where they have left the conditions for the creation of hydrocarbons has been a matter of accident—a rare and specific sequence of geologic events.

Numerous of those sequences happened in what is called the Atlantic Margin, a string of basins that links Europe, Africa and North and South America, following a path from Tierra del Fuego and the Cape of Good Hope in the South Atlantic to the northern waters off of Newfoundland, Greenland and the United Kingdom. Theoretically, you can drill anywhere on either side of these once-united continents and find oil or gas.

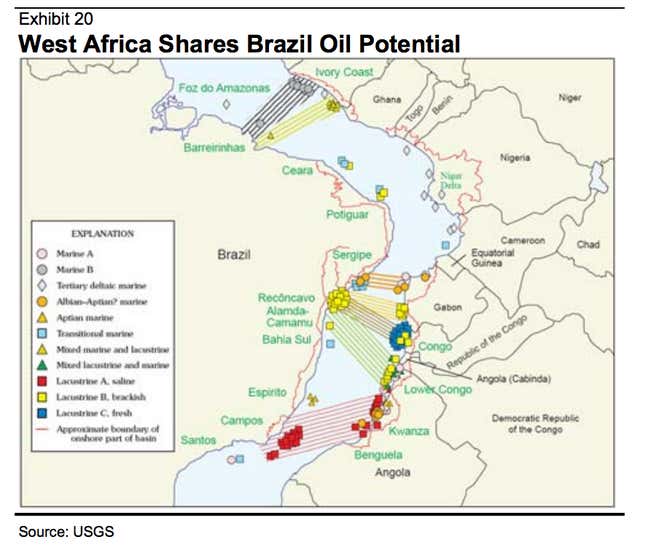

When American oil lobbyists advocate drilling offshore from Virginia, they are hoping to tap the geology of the Atlantic Margin. A rush of interest to drill offshore from Namibia (paywall) is the same play. In 2007, Tullow Oil made a discovery offshore from Ghana. From there, the UK-based company went straight across the Atlantic to French Guiana and, in 2011, found an oilfield called Zaedyus. After 20 billion barrels of oil were discovered in offshore Brazil, frenzied oil companies explored the opposing geology in deepwater Angola where, in 2012, they found petroleum in a play called Kwanza.

The analog logic is also behind far-flung oil company interest in offshore Portugal, Gabon, Newfoundland, Suriname and more. All of it goes back to the breakup of Pangaea. “Analogs are a great tool of exploration. You get to know something. You can touch and feel,” said Geir Richardsen, vice president of exploration for Norway’s Statoil.

Getting the go-ahead

Even if the project validated MacMullin’s hunch, Wilson advised him to be prepared for serious resistance. Oil companies that had already spent time and money prospecting off Nova Scotia might be offended by the suggestion that they had simply overlooked something. Still, what Wilson had in mind would not be unprecedented, he said, and it was the right approach to attract a supermajor. Companies routinely revisited their rivals’ failed fields, figured out what went wrong, and emerged with big discoveries, often using meticulous paleogeological reconstructions of the sort Wilson had in mind.

When done well, such models could convey a remarkably broad story, linking together the earliest geological tale of sprawling, often disconnected regions. If you were a mid-level manager at a supermajor and wished to sell your boss on a new play, an analog was a good way to do it—a sensible story that could carry outsized authority, giving the impression that the risk of a dry hole had been at least partly eliminated. So quite apart from the secrets that analog exploration could unlock, Wilson’s suggestion also shrewdly captured industry psychology.

But Wilson’s fee was high. For a big oil company, worth hundreds of billions of dollars, a $15 million analysis would be trifling, but not for a place like Nova Scotia, which was $15 billion in debt from years of overspending. It had no slush fund for eccentric, high-risk projects. Ministers wanted to know what RPS could possibly learn “that the big oil companies couldn’t figure out.”

“Either we spend the money, or we give up,” MacMullin replied.

The request went all the way up to the premier, Nova Scotia’s top political leader. MacMullin got the money.

“Now we were onto something,” MacMullin said. “There was no guarantee it would turn us around. But it was our best chance.”

Nova Scotia’s decline

Gordon Stevens owns a patio cafe in Halifax called Uncommon Grounds, in a manicured downtown park that is tended like the Victorian-era garden it once was. Stevens grew up in Cape Breton, the northern island of Nova Scotia. In 1914, his great-grandfather, Gordon P. Stevens, opened a general store on the island, in the fortress town of Louisbourg, selling supplies to cod fishermen and families associated with the shipping industry.

But three generations later, cod fishing collapsed. When Gordon’s father, Doug, retired in 1998, he closed the store. Work had generally left the town. Today cod and haddock are still caught at sea, but they are immediately gutted and frozen for shipment to China, where they’re processed further, then shipped back again to Massachusetts and New Hampshire fish sticks factories. That part particularly galls Stevens—how it could be cheaper to ship cod to China and back to the US, just to turn it into cheap fish sticks, than to process it here in Nova Scotia.

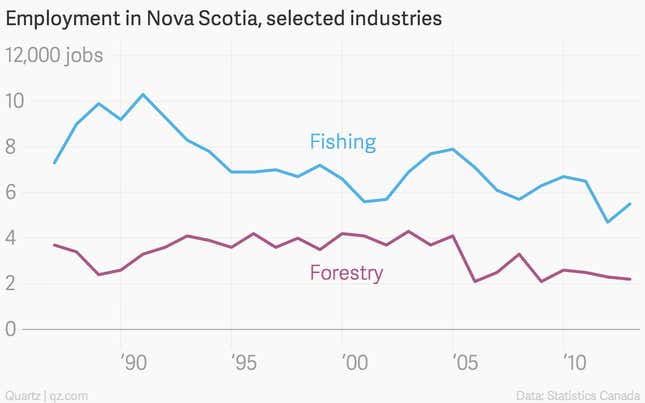

That loss of the fish sticks business reflects a general hollowing-out of work. From 1990 to 2010, Nova Scotia had the lowest growth of any province in Canada, at 1%, and the lowest GDP per capita at $37,349. As the fish population collapsed in the early 1990s, so did employment on boats, plunging by 49% by 2012, according to official records. Lumber exports fell by 58% and the demise of newspapers resulted in a closure of sawmills. In Cape Breton, a third of the population aged 30 to 39 cleared out. In one county—Guysborough—more than half of the working-age population moved away. Stevens himself went and found work in the Cayman Islands.

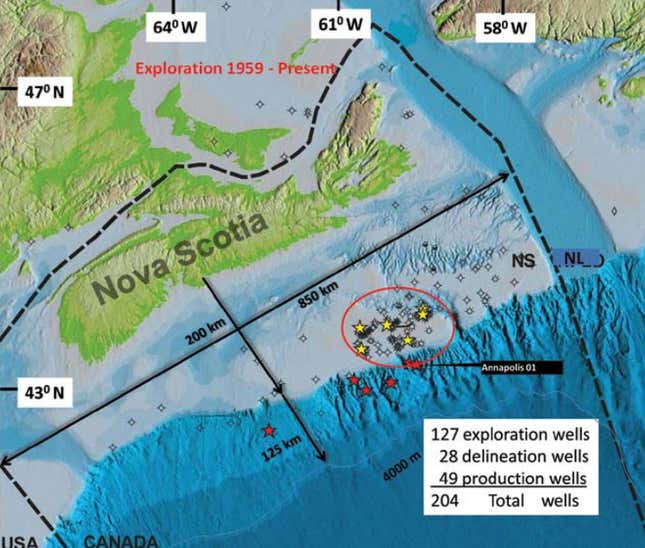

The oil industry mirrors the general decline. By the time MacMullin’s boss told him “I want a plan” in 2007, Nova Scotia’s drilling days were thought to be over. Oil companies had been exploring since 1959, and until 1986, almost one in four wells they drilled found commercial gas—an enviable record for the period. But since then, only one of 36 wells has struck commercial hydrocarbons. And the volumes have been relatively paltry—roughly 2 billion barrels of recoverable reserves in all the finds. (In the United Arab Emirates, that’s the lifetime average of one single well.) The spate of dry holes, along with the high cost of working on the often harsh frontier, led most of the explorers to relinquish their remaining rights to drill and pack up for prospects elsewhere.

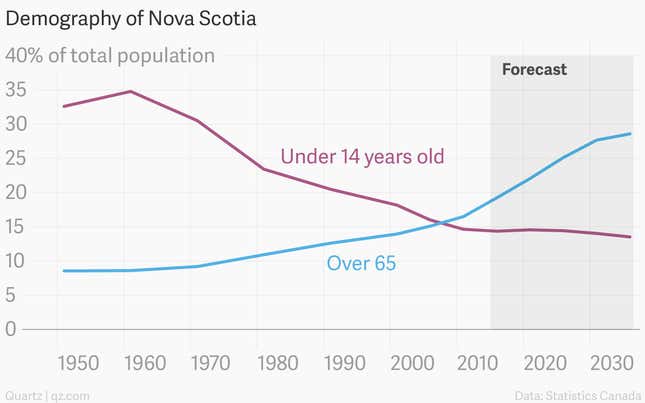

The province’s predicament was summed up neatly last February in a 258-page government-commissioned report titled Now or Never: An Urgent Call to Action for Nova Scotians. Its principal author, Ray Ivany, president of Acadia University, about 60 miles northwest of Halifax, said he did not mean to “raise panic bells,” but that he had to be blunt. “We are teetering on the brink,” the report said. “There is a crisis, and it does threaten the basic economic and demographic viability of our province, most dramatically in our rural regions.” The population was aging—the number of Nova Scotians over 65 grew 26% from 2002 to 2012, to reach 17% of the population, the highest proportion in Canada, while those under 15 were just 14.5%.

Indeed, in March of last year, the town of Springhill voted itself out of existence, citing its declining population and economy. About 10 other rural towns, officials say, are also on the verge of failure and dissolution.

In the beginning: The Bahamas, 203 million years BC

The British consultants became MacMullin’s partners in saving Nova Scotia. Wilson, whose father and both siblings were also geologists, was joined by three other BP veterans. Together, they set out to reconstruct the world starting a little over 200 million years ago. “We needed to put the continents back together,” Wilson said.

The time they were looking at was one when the united Nova Scotia and Morocco were situated near the present-day Caribbean. If a dinosaur were inclined to roam 300 or 400 miles, it could have walked from Halifax to Rabat. Balmy and leafy, Pangaea was in the throes of breaking up.

As the inexorable currents of molten rock inside the earth slowly drove the continents apart, there was first cracking, followed by an explosion. Magma ejected violently. Rifts opened in Pangaea corresponding roughly to the coastlines of present-day Canada and North Africa. Seawater flooded in. A coral reef the size and appearance of the Great Barrier Reef began to form—an ancestor of today’s Bahamas.

Over tens of millions of years, that water would broaden into the central Atlantic Ocean. But to begin with, it was shallow. It would evaporate in the tropical heat, then build up again before vanishing anew, resulting in a thickening salt plain. When the water was there, it supported the presence of billions of marine animals, both tiny and larger. In the dry periods, the animals died and became buried in mud and sand landslides. Gradually they merged into a gigantic mass of gunk—salt, dead organisms and sediment, all of it piling up in a gently subsiding basin.

For these organisms to transmogrify into an oilfield would require a fortunate sequence of events.

First, the muck of organisms, sand and mud had to harden into rock. Then it had to ferment, or “cook”, for tens of millions of years. This cooking would have happened in what’s called “source rock,” which is dense, like shale or sandstone. Source rock is the fundamental component of an oilfield, the kitchen for the creation of oil and gas.

But getting oil straight from source rock is difficult. The rock is too dense to allow for the easy extraction of embedded liquid molecules. Onshore and in shallow waters, oil companies use hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” techniques to blast cracks into source rock and release the oil, but fracking at the ocean depths where MacMullin and Wilson wanted to look is exceptionally difficult and expensive, and companies are only just starting to take it on.

So for the oil to be easily accessible, the next step it must take after “cooking” in the source rock is to naturally seep out and be captured within a larger, outside container—a reservoir. An oil reservoir is not like a gigantic tank or swimming pool: It’s just another mass of rock. But it has larger pores. Those pores are linked—they run more or less in a sequence that allows the oil or natural gas to be freely pumped from the ground.

Finally, the reservoir has to be self-contained: sealed off by something else, such as another kind of rock, or a cap of salt. If not, the hydrocarbons will leak away and be lost to the subterranean world.

So Wilson had to show that this chain had unfolded perfectly in Nova Scotia. None of the steps could be missed. For starters, his team had to discover how long the initial process had gone on—how long that narrow stretch of water between the future opposing continents was shallow. Then, what did the waters look like—were they clear and blue, like a Bahaman cove, or green, saline and malodorous like a Florida marsh? To create a soup of hydrocarbons, the conditions had to be anoxic and relatively stagnant—the water had to be a lagoon with restricted oxygen and circulation. The more stagnant the better.

And it had to have persisted that way for 10 or 15 million years. If the waters had been deep, open and agitated—or if they had been shallow and cut off, but for only a few million years—there was no reason to look any further for oil. The muck would not have fermented into hydrocarbons, and MacMullin would have to conceive another plan to save his province.

The Halifax effect

Trevor Adams, who runs a local magazine in Halifax, reckons that no one outside Nova Scotia’s oil game itself has given a thought to the possibility of oil. Nova Scotians, he says, have by and large lost hope in such luck.

Adams himself grew up in a village called Westport. The men there would fish for scallops and lobster for three months, which earned enough to live for the rest of the year. But now there is a glut of such seafood and little work. He said the town—once 500 residents—has dwindled to just 150. Few of working age can think of any reason to stay.

John Demont, a business columnist at the local Chronicle Herald, tells a similar story about his hometown of Sydney, where his and his friends’ fathers and grandfathers mined coal and made steel for the gigantic Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation. Now Dominion is closed, and local men board a weekly plane at the nearby airport for the flight to Alberta to work the oil sands fields. When the plane lands, they take the places of men disembarking from the same fields. Such men held little store in tales of Nova Scotian booms. “We’re always hitching our wagon to someone. ‘We’re all going to be rich!’” Demont said, not smiling.

Haligonians say experience has led them to be predisposed to be reserved, not to flaunt themselves, and above all else not try to achieve too much. One hears much mistrust of hifalutin’ business successes who become full of themselves, something the author of the government report, Ray Ivany, called a tendency to more harbor “suspicion about [entrepreneurs’] motives than … to celebrate their success.”

It stems partly from a huge chip that Halifax has on its shoulder. In its centuries of history, it has been on the edge of numerous events—all the major wars, local and global, since the US Revolutionary War. With little prompting, Haligonians recall their outsized disasters—among them a two-day brawl by 12,000 sailors in 1945, who celebrated Germany’s surrender by attacking some 850 shops, many of which had gouged them mercilessly during the wartime business boom. And the 1917 explosion of a French cargo ship loaded with munitions that killed some 2,000 people and burned large parts of the city, in what before Hiroshima was called the largest man-made explosion in history.

This is a city not only with a chip, but a black mood. Visit Bookmark on Spring Garden Street and, on the local authors’ shelf, consider the titles: Death on the Ice, The Town that Died, The Gale of 1929, and, of course, Shattered City. Haligonians simply retain faith in few. It hasn’t helped that they’ve been fibbed to—a lot—in the view of many people here. According to Gordon Stevens, Nova Scotia is a magnet for fly-by-night operators, big talkers who “say they are going to change the world” but don’t. He thought about that a few weeks before, listening to a group of Chinese describe plans for 800 cabins on Nova Scotia’s eastern shore, in Guysborough County, along with a theme park and a movie studio. “Would it be great if it worked out? Yes. Do I think it will happen? Not a snowball’s chance in hell,” Stevens said.

Stevens himself is a bit of an outlier. After spending some years in the Caymans, he returned to Nova Scotia in 2002 and opened Uncommon Grounds, his cafe, and later a few other businesses. They cater to what he said was the only way Nova Scotia would survive—by not trying to undercut anyone but concentrating on value, quality and brand.

One thing that Stevens is definitely not thinking about is an oil rush. Apart from MacMullin and his guys, no one seems to be. “I’m as optimistic as it’s safe to be,” Stevens said. “But I’m not about to open a new store in hopes they strike oil.”

Enter the paleomagicians

To find the evidence that the break-up of Pangaea had led to the happy sequence of events he was looking for—a shallow, anoxic lagoon full of biomatter that hardened over millions of years into source rock, cooked into hydrocarbons, then seeped out into a reservoir and was trapped—Wilson would need to assemble a broad team of experts: seismologists, geochemists, hydrocarbon geologists, volcanic specialists. But for starters, he required just one expertise: plate tectonics.

Paleogeologists, as such scientists are known (one admirer at Halifax’s Dalhousie University called them by another common term–“paleomagicians”), decipher the past by plotting the shifts of the world’s nine major tectonic plates, then depicting the results on maps. Paleogeology is not a hard science in the sense of chemistry or biology—the passage of time and the dependence purely on the geological record mean the data require a lot of interpretation and leaps of judgment. Disputes are legion over what rock was precisely where and when, what substances or minerals collected within the Earth, and how you ultimately could extract them. So even if Wilson’s team discerned evidence of a substantial hydrocarbon system—source and reservoir rock, along with an estimate of the reserves contained within—their view would be subject to challenge.

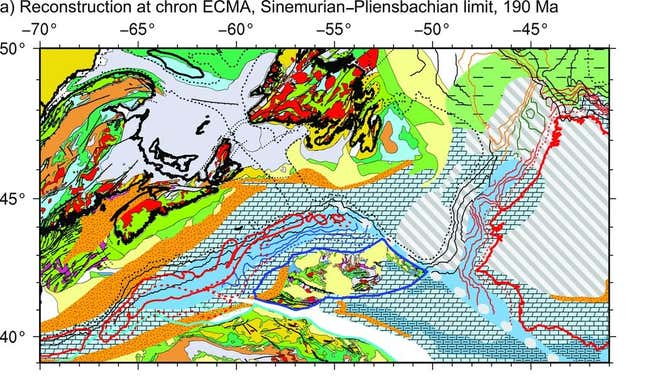

Wilson’s paleogeologists were led by a Frenchman named Jean-Claude Sibuet, a specialist on Iberia and North Africa. He would now combine his data on their geology with research into Nova Scotia.

One of his main tools was the seismic record: the detailed subterranean maps that oil companies had created over the years by bouncing sound to the sea floor from ships on the surface of the water. In the 1960s and into the 1970s, the industry standard was maps that showed a two-dimensional picture of the geological depths. These were the kinds of maps on which the oil majors had hitherto been relying in Nova Scotia. They had resulted in a terrific record of discoveries around the world. But there also was a high failure rate since such maps did not reveal complex plays—the multi-layered geology that could lie beneath the surface.

Sibuet, instead, took advantage of three-dimensional seismic portraits, pioneered by ExxonMobil, that reveal hidden twists of geology channels. Sibuet’s slides married existing two-dimensional and three-dimensional maps and other data to produce the first known 3D portraits of the Nova Scotian offshore from the Pangaean breakup forward.

Exhibit 1: The geological record

Sibuet’s months of research would ultimately boil down to a presentation just seven slides long. The pivotal one, above, shows the world 190 million years ago, shortly after Pangaea began to come apart. On the map, in red, Sibuet’s artists drew a long, meandering, narrow, southwest-to-northeast oval, visible in the left lower quarter. The red represented strong magnetic traces his team had found in the seismic record. These were evidence of active volcanoes: a four- to nine-mile thick body of lava.

That showed that the waters had in fact been shallow—between a few meters to a few tens of meters in depth. These sizzling, roiling volcanoes, which seemed to rise up everywhere from the earth and sea, were a source of heat that kept the geology from sinking and creating a deeper waterway in which the hydrocarbon muck that was the precursor of the source rock would not have managed to form.

For Sibuet, this was evidence of the largely closed, listless marine environment for which Wilson hoped. As Sibuet read the data, the waters were lethargic, the circulation cut off on three sides, all around apart from the south, which was closed off enough. That slide was the centerpiece of how Wilson would argue to the big oil companies that a hot, anoxic and shallow sea existed for 13 million years, enough time to put down the basics for the creation of rich source rock.

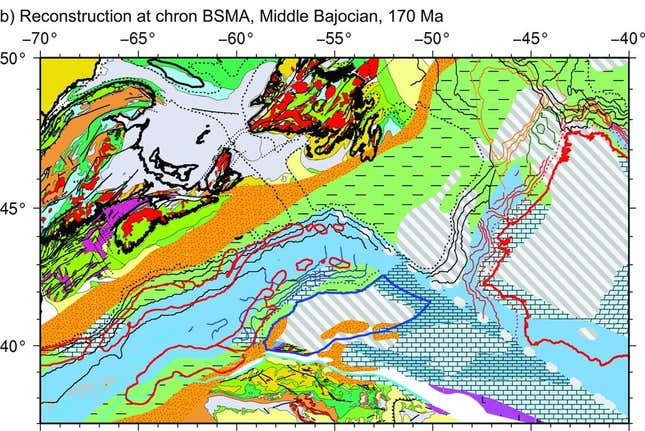

Sibuet next pushed ahead by 20 million years. He was looking for a reservoir that, when oil seeped out of the source rock, would keep it bottled up. At 170 million years BC, Sibuet found the ingredients of this reservoir in the beginnings of a river system. It was the precursor to the St. Lawrence River, which today drains the Great Lakes into the Atlantic. In those years—the Middle Jurassic era—the river would have carried sand and mud off of North America and into the deepening water between Nova Scotia and Morocco. Over time, this sediment would have compressed into sandstone, one of the best porous reservoir rocks.

In addition, Sibuet knew of the presence of salt—the remnants of the flats created in the baking sun 30 million years before. That could serve as a cap or canopy on the reservoir and seal in the elemental hydrocarbons.

Wilson and his team concluded that by this stage the marine organisms—lodged in source rock below the Earth’s surface, covered with the sediment and salt, and under immense pressure—would have begun to cook at temperatures that eventually would reach up to 150°C (about 300°F). It would be tens of millions of years before it was ready for migration to the reservoir.

To the analysts beholding these initial findings, it was thrilling stuff. The rudimentary structure of offshore Nova Scotia looked a lot like the undersea Gulf of Mexico, and even the Niger Delta, two of the richest oil plays in the world.

Yet it still wasn’t enough. To persuade the big companies, it was important to establish that this was no localized event but had happened elsewhere—that there was an “analog”.

Exhibit 2: The Moroccan analog

For oil companies, the presence of geological analogs is both comforting—they demonstrate latitude for a broader search should one particular well prove dry—and exciting: when a play looks big, it can create an industry frenzy. Wilson wanted to generate precisely such a response by showing that the rich hydrocarbon system of which he believed his team by now had ample evidence was in fact much, much larger—that it continued hundreds of miles north along Nova Scotia’s coastline up to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

In this respect, the evidence he had in hand so far was not promising. The volcanic signature of a restricted marine environment, the indicator of source rock, faded as you went north, then vanished altogether. But the team wanted a whopper of a story to tell the oil companies. If they couldn’t find the answer they sought in Nova Scotia, perhaps they could in Morocco, where oil companies had been prospecting even longer than they had in Nova Scotia.

To find out, a member of Wilson’s team called the Moroccan state oil company. Morocco had commissioned a good offshore seismic survey in 2001, and he had a friend there. Could he have a copy of the results?

When they inspected what the Moroccans forwarded, Wilson’s team concentrated on the geology that formerly conjoined the north African country and Nova Scotia—the connecting tissue known as the conjugate. They pretty instantly spotted what they were looking for—seismic lines suggesting volcanic material extending far toward Morocco’s northeast.

This was the prize. If Morocco had such volcanics, that potentially meant considerable hydrocarbons, and “if it’s present in Morocco, it has to be in Nova Scotia,” said Matt Luhesi, Wilson’s deputy. “You can’t have a one-handed clap.”

The evidence went both ways. The evidence in southerly offshore Nova Scotia demonstrated potential hydrocarbons in the mirror region of Morocco, and the report from Morocco stretched Nova Scotia’s hydrocarbon zone north. The respective evidence was self-reinforcing and suggested the presence of future rich discoveries in both places.

But that still wasn’t going to be enough.

Exhibit 3: The chemical trace

In January 2011, Sandy MacMullin arrived with Wilson’s team in the French capital. There, a group of experts from four supermajors would examine the findings. Before MacMullin went into high-stakes presentations with the oil companies, he wanted fair warning if they were missing anything.

For a day and a half, the reviewers scrutinized Wilson’s model. When they were done, they met with MacMullin and Wilson’s team. They were impressed, they said: The paleogeographic evidence was precisely what a supermajor itself would assemble before a big investment decision. And they knew of no nation or province around the world that had bothered to present its case in the form of the tectonic record. Usually, only oil companies bothered to do such scrupulous preparation.

Except, they said, that the case was still incomplete. Yes, Wilson’s team had far surpassed the basics and asserted the potential for a vast new hydrocarbon region, one that the industry itself had missed despite drilling 127 wells. It was a region extending along both sides of the central Atlantic in the early Jurassic era, an older subterranean dimension than those explored by prior drillers. The analog argument—the team’s interpretation of volcanic, seismic and magnetic data in both Nova Scotia and Morocco—advanced this. It made a forceful case for the conditions in which oil could have formed.

But the reviewers wanted signs that such conditions actually existed. They sought what is called geochemical validation, another standard oil prospecting tool. If Wilson’s team could provide some solid geochemistry, “you will have a pretty compelling story,” a reviewer said.

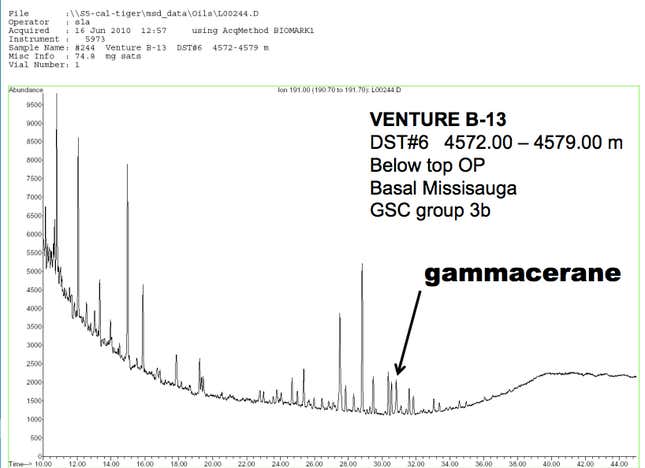

The critique was a reference to the presence—or absence—of gammacerane (pronounced guh-MAH’-suh-rain), a substance known as a biomarker. If oil has moved through a rock, it leaves behind such traces. So does hypersaline, swamp-like water, the type that would have been present in the volcano-induced, shallow and restricted waters that Wilson’s team concluded had persisted for 13 million years. If northeast Nova Scotia’s offshore rocks had traces of gammacerane, it would be the defining verification of the conditions necessary for a hydrocarbon province. The reviewers were not being capricious—Wilson agreed that the oil supermajors were much more likely to change their opinion if gammacerane was found.

Nova Scotia maintains a library of samples from all the wells drilled offshore over the decades. A member of Wilson’s team began to scrutinize them. Three months later, he came upon traces of gammacerane in a sample from a dry well drilled by a Canadian company in 2004. That confirmed that the rock had once been part of a hypersaline swamp, adding a bolstering cushion to Wilson’s hypothesis that entirely new, unexplored source rock lay off of Nova Scotia’s shores.

But that was not all: Wilson’s geochemist went on to cast his search across the central Atlantic, and found more gammacerane—in wells in the Canary Islands, in Newfoundland and Portugal. The oil province that Wilson was depicting was potentially very large, all of it going back to the original configuration of Pangaea.

MacMullin and Wilson’s team readied to visit the supermajors.

The moment of truth

When oilfields are put up for lease, the seller, whether a country or a locality, typically charges a fee for access to the data required to understand their value—the seismic studies, reserves estimates and so on. The rationale is to immediately weed out unserious bidders, as well as rivals that may simply wish to understand a competitor’s assets. Not MacMullin, though—he decided that the 350-page atlas of its offshore that had cost Nova Scotia $15 million would be given away for free. For him, worse than the possibility of theft or caprice was the risk that a supermajor might not even look at Nova Scotia’s reinterpreted geology. In July 2011, MacMullin’s technicians posted the atlas on the Nova Scotia government website, where you can still read it.

Wilson’s team had put Morocco and Nova Scotia back together. Slides showed how the two rifted apart in the early Jurassic era, along with microscopic fossils that probably generated oil, migrated into sandstone and were trapped there. They had calculated how much in the way of hydrocarbons were probably trapped—8 billion barrels of oil and 120 trillion cubic feet of gas, four times more than had been discovered to date in the entire province.

Wilson told the companies that the problem all along had not been the geology, but where companies had drilled. They needed to follow former rivulets coming off of the main ancient St. Lawrence river, deeply buried channels in which sandstone reservoirs had stealthily formed.

In meeting after meeting at supermajor offices, Wilson and Luheshi, his deputy, explained their findings. With questions, each meeting took two to four hours. Of the specific spots where they were suggesting the companies look, Luheshi said, “If I was going to bet my grandmother’s money, that is where I would drill for oil offshore Nova Scotia.” If they were right, Luheshi would say, “it will be a major new oil province.”

The response, MacMullin said, typically went like this: “The first hour would be polite. The next hour, they were getting their pens out and taking notes. The third hour was…” and he mimicked staring into space, loose-jawed, wide-eyed, shaking his head.

Months passed with no positive responses. Some of the companies passed—ExxonMobil, for example, declined to bid. But in January 2012, MacMullin received the news that Shell would pay $970 million for rights to explore in 2,000 meters of water. Ten months later, BP bid even higher—$1.05 billion—for rights to drill right alongside Shell. Two of the world’s five biggest oil companies had jumped in with both feet.

The waiting begins

Shell will begin to drill first—it plans to sink its first well in the second half of 2015. Its results will be the first sign of whether MacMullin was right; BP plans its first well in about two years.

With world oil prices crashing, continuing to explore might seem foolhardy. In recent weeks, oil companies around the world have slashed their exploration budgets. But neither Shell nor BP has so far cut Nova Scotia. A Shell spokesman said one reason is that this stage—drilling a single exploration well to try to determine whether there is oil—is comparatively cheap. It is later, when fields are developed, that the big costs come. And the timetable for such oil projects is long; there is no knowing where prices will be by that stage.

A number of leading petroleum geologists are still critical of analog exploration. They say that mirror-imaging is an interesting framework for exploration but that you can’t blindly go from one basin to another just because they were once fused. Much has happened in the tens of millions of years since that will make them different, often fundamentally so. No two basins are identical, they say, even when they start out as one.

Yet 11 months after signing the Nova Scotia deal, BP bought into its direct analog in offshore Morocco, explaining to its shareholders that the two were effectively identical and organizing them as a single venture (pdf, p. 20). Its more than $1 billion of planned spending in the two places is squarely an analog play. Last year, the British company conducted seismic tests of its Nova Scotia blocks.

Even if no oil is found, John O’Leary, a senior BP executive, said the ambition of MacMullin’s approach was important to his company’s decision. Giving away the results of the survey “sparked a lot of interest.” Other petroleum states should pay heed, he suggested. “Nova Scotia spent $15 million and got a $2 billion return,” he said.

And what if the oil is found?

An oil boom can and does wallop the place where it occurs, and sometimes, if it’s big enough, its neighbors as well. This has been a feature of oil since the first gushers 140 years ago in Pennsylvania and Baku. Today, look at Accra, Atyrau, Erbil and Maputo, not to mention Williston, North Dakota—all former backwaters overrun in varying degrees by cash and newcomers drawn to the respective El Dorados. Such booms typically attract tens of thousands of outsiders—oil hands, of course, but also accountants, lawyers, haberdashers, restaurateurs, hoteliers, building contractors, luxury shopkeepers of various sorts, automobile showrooms, garages and filling stations, and more.

There is a reasonable chance that Halifax will be next. If it is, that will in a big way be a blessing for always-the-bridesmaid-never-the-bride Nova Scotia. But oil booms also almost always tear at the fabric of places they touch—old and fragile communities are particularly at risk.

There are plenty of cautionary tales. Ghana became a magnet for fawning foreign investors and hangers-on after oil was found 2.8 miles below its offshore waters seven years ago. But it has become clear that the country is failing to manage the bonanza well: The population of 26 million has endured fuel and electricity shortages. In June last year, politicians decided to cut local power to aluminum smelters so Ghanaians could watch the World Cup. The humiliation reached a crescendo in October, when the International Monetary Fund had to step in with an $800 million bailout.

Nova Scotia, of course, is hardly comparable to Ghana; its GDP per capita is some 20 times as big. But the same story has repeated up and down the southern Atlantic Margin, where pockets of new wealth have sprung up in bastions of corrupt autocracy. The few places that have handled their oil right—Alaska and Norway, for instance—had, almost as a first order of business, established long-term investment funds, meant in part to improve the current lifestyle but more to support a future when the oil is gone.

Halifax is not innocent—with its long history as a garrison city and military port, it has seen bawdy times. Despite it all, Haligonians talk like unexposed townspeople everywhere, a genteel unworldliness that carries over into the feel of their city—low-slung, shopworn, yet somehow fresh. One wonders what would survive the teems of oilmen and carpetbaggers, the skyscrapers, and the billions of dollars of temptation.

Perhaps because of their general skepticism, Haligonians seem oblivious to the danger. In government offices, shops, restaurants, and on the street, you hear a philosophy that, despite the fact that two supermajors have committed serious investment dollars to drill offshore, there simply is no reason to contemplate what-ifs. An oil boom? What are you talking about, an oil boom?

Not that no-one is thinking to the future at all. In recent years, Halifax has ripped up a string of parking lots on the waterfront and built a wooden promenade. Construction is going on, and the tawdriness becoming less and less. Andy Fillmore, a city planner who supervised much of this sprucing up (and is now running for Parliament), grew up in Halifax, the son of a mathematician father who taught at Dalhousie, and he has further dreams for the city. He wants it to be like Copenhagen or Stockholm—a city with “the most delightful urban core where people would be drawn to live in. Why have two cars when you can walk wherever you want?”

Like everyone else, Fillmore says he does not dream of oil riches, although, when pushed, he wonders aloud whether, if it did come, “are we going to be like the kid with the new car who crashes it?” In Fillmore’s mind, Halifax’s likelier future is tourism. One scheme on which his team is working at the moment is positioning the city as a destination for super-yachts, the oversized vessels on which the world’s new class of hyper-rich sail the seas for three or four months a year. He said, “The amount of money they spend while in port is phenomenal.”

Even Sandy MacMullin, who knows more than anyone else in the province about the prospects for oil, sees no reason to look too far ahead. “When you are trying to balance a budget and make payments on principal,” he said, “debt tends to take the priority.” As it is, provincial officials are pretty happy with him now—they are no longer resisting his ideas. In May, the government allocated another $12 million for seismic and other geological studies. “It’s planning for success,” he said.

A week or so after my conversations in Halifax, an email arrived. It was from Fillmore. “I have been telling the story of our discussion to various well-placed folks in the city,” he wrote. “To a person, people have been having the same reaction that I had to our lack of a plan should the offshore hit.” He said people respond first with a kind of open-mouthed surprise, then with a sense of urgency about how they can get a plan in place. And so Fillmore had a question for me: Whom do we call in Norway for advice?