Savoring the suffering of others isn’t merely the stuff of Fifty Shades of Grey or Hannibal Lecter. Recent psychology research reveals that most people are more likely to encounter sadism in their offices, at the hands of a colleague, than from someone with a flogger or a glass of chianti.

That boss who seems to love chewing out his underlings in front of the entire team? He could very well be an “everyday sadist,” the latest addition to what scientists call the “Dark Tetrad”—personalities that feature ”socially offensive traits falling in the normal or ‘everyday’ range” of behavior, as Delroy Paulhus, a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia put it in a recent paper (paywall).

Alongside everyday sadism, Dark Tetrad personalities include narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. These individuals may be malevolent, but not so much that their day-to-day functioning is impeded or that they will land in prison or a psych ward.

In fact, Dark Tetrad personalities may have some advantages over the rest of us.

Blessed with a surfeit of confidence and knack for lying, they dazzle in interviews, make great first impressions, and often shoot effortlessly up the org chart. Take, for instance, corporate psychopaths: Psychologists estimate a concentration of psychopathic people in corporate senior executive roles that’s nearly four times the rate they exist overall.

“Many features of corporate psychopaths can be mistaken for leadership or positive traits,” explains Cynthia Mathieu, professor of organizational psychology at Universite du Quebec a Trois-Rivieres and an expert on white-collar psychopathy. “For instance, their lack of emotional responsiveness can be seen as a good business trait for leaders to possess, their grandiose promises and ambition to be successful can be seen positively for corporations.”

Narcissists too excel. Once at the top, narcissistic CEOs command higher salaries (pdf) than nicer leaders. Among West Point cadets, the personality trait is the single biggest predictor of success.

But despite the confidence a narcissistic person can inspire, says Daniel Jones, professor of psychology at University of Texas-El Paso, there’s usually “not much rubber meeting the road in terms of what they actually get done—they’re exaggerating their skill set and their knowledge.” And thanks to a proclivity towards reckless decision-making and morally lax behavior, these people are “not good to have around other people’s money,” he adds.

Like psychopaths and narcissists, people with Machiavellian and everyday sadistic personalities also have few qualms about lying and exploiting others to get ahead—which is a big reason why Dark Tetrad types also make life hell for their employees. The more psychologists learn about how these personality types thrive in the workplace, the more urgent they say it is to limit the Dark Tetrad’s destructive potential—piquing tough ethical questions about how exactly to do that.

The above table comes from UBC’s Paulhus’ recent paper. Here’s a more detailed breakdown of how people within the Dark Tetrad tend to excel—and what leads to their undoing:

Psychopathy

Psychopathic personalities are impulsive thrill-seekers, known for their need for instant gratification, pushing limits, and a lack of emotion. They respond little to the anxiety, fear, embarrassment, and guilt that can wither the resolve of their peers, allowing them to pull off feats of daring with chilly aplomb. They’re prone to picking fights and share with narcissistic personalities galling levels of entitlement and a belief in their own superiority. (We’re not talking about Ted Bundy-type psychopathy here. These are people with higher levels of psychopathic traits than the average person, but not as high as clinically diagnosed psychopaths. Or, in psychological parlance, they’re “subclinical.”)

Short-term advantages: Keeping cool under fire helps people with psychopathic personalities excel in any process where competition is a part of selection—as does their easy charm. They’re comfortable taking big risks and making tough decisions, and seem to be willing to succeed at all costs. Their tendency toward impulsiveness can seem like creativity, and their cool confidence often make excellent impressions on interviewers and superiors. Evidence suggests that the more psychopathically inclined gravitate more toward jobs in finance and civil service (paywall), which are more competitive, while avoiding retail and manufacturing. In his book The Wisdom of Psychopaths, research psychologist Kevin Dutton reports that, according to the results of his own psychopath survey, these are the professions in that tend to have the highest and lowest concentrations of psychopathic personalities:

Long-term problems: Though their superiors struggle to distinguish between a psychopathic individual’s behaviors and traditional leadership skills, the psychopath’s underlings tend to have a better sense of the real deal. Studies suggests that psychopathic people tend to struggle as managers, team players, and in overall achievement. “As with narcissistic personalities, the most destructive impact of psychopathic personalities in the workplace would be on coworkers or employees,” says Mathieu. “Our studies suggest that corporate psychopathy in leaders is associated with increased levels of psychological distress in employees and decrease in their job satisfaction.”

Impulsive and often aggressive, psychopathic-minded people tend to fly off the handle or offend others just because they feel like it, destroying office morale and, in the extreme, creating a culture of fear. Though effective psychopathic personalities carefully project a winning image to their superiors, eventually their abuse of their peers and subordinates surfaces. And while some with psychopathic personalities can thrive as long as their interests are aligned with those of the company, their lack of concern for rules or laws makes them likely to commit crimes, possibly even on behalf of the company. The more power they’re given, the easier it is for them to destroy corporate value by taking unnecessary risks or making impulsive decisions.

Possible examples:

- Lyndon B. Johnson. The US president was known for his dominant social style (his narcissism was also off the charts).

- James Bond. The fictional spy created by Ian Fleming is known for his knack for killing and his coolness in the face of danger.

- “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap. The turnaround specialist and former CEO of Sunbeam is famed for firing thousands of employees without warning.

- Gordon Gekko. The ruthless finance wizard played by Michael Douglas in Wall Street, whose most famous line is ”Greed is good.”

Machiavellianism

In the early 1500s, Niccolò Machiavelli wrote the classic tale of manipulation, The Prince, to expound on his cynical philosophy of how to rule. Those who live by his credos today are “high Machs,” as psychologists casually refer to them. These folks are known for their single-minded, strategic focus on their own goals, a knack for lying to and exploiting others, and disdain for rules.

Short-term advantages: They’re calculating, manipulative, and tend to be long-term planners. In an intelligent person, a Machiavellian personality can make an excellent negotiator or a politically adroit climber. They eagerly exploit suckers and have no qualms about making themselves look good. They flourish in workplaces with looser organizational structures.

Long-term problems: Given enough time, a high Mach can turn a company into a political snakepit, eventually weakening morale. Their disdain for rules ends up embroiling Machiavellian folks in corporate malfeasance and white-collar crime. Since they tend not to indulge in reckless behavior, are not grandiose, and operate secretively, those with Machiavellian personalities can be tough to identify.

Possible examples:

- Bernie Madoff. Investment adviser who fleeced thousands of investors with the biggest Ponzi scheme in history.

- Jeff Skilling. Former Enron CEO and mastermind of the accounting shenanigans that led to his company’s enormous securities fraud.

- Francis Underwood. The éminence grise on Netflix’s House of Cards (though some put him in the psychopath category).

- Petyr Baelish. Also known as “Littlefinger,” this character from Game of Thrones is a master manipulator who acts without conscience.

Narcissism

The name comes from Narcissus, the hunky Greek mythological character who became so besotted with his reflection that he starved to death. Modern-day narcissists have a grandiose obsession with their own image that can be similarly destructive. These characters are known for their natural charm, knack for self-promotion, and need to demonstrate their superiority.

Short-term advantages: Those with a healthy dose of narcissism will stand out in job interviews, which is one of the only social situations where brazen boasting is acceptable, as UBC’s Paulhus told the Telegraph (paywall). Dazzled by their breezy confidence and impressive skill set, managers often hire them with plans for swift promotion. Narcissistic personalities are not only deft at sloughing off their work and for blaming others, they also take credit when it’s undeserved. By the time something starts to seem fishy, their promotion paperwork is already filed with HR. Narcissism has much in common with psychopathy; as a narcissistic person’s career progresses, they exude leadership skills, even as those beneath them suffer.

Long-term problems: As narcissistic personalities saddle peers and underlings with more of their work, it can ruin office productivity. Studies show that narcissists tend to double-down when questioned or challenged. Jones points to research showing that in a gambling game stacked against winning, while Machiavellian and psychopathic personalities took risks more often, narcissistic folks lost more money overall. “They tend to double down on what’s failing—they’re very arrogant that way,” says Jones. “They have an insistence on being right and a lack of willingness to listen to subordinates.”

As a result, they court more corporate catastrophe the higher they climb. As narcissistic people rise, they surround themselves with yes-men since they can’t take criticism, which is why having a narcissistic CEO can be disastrous. Even when a narcissistic boss knows his company is struggling, his conviction in his own superiority can make it worse. Analyzing data on S&P 500 CEOs between 1992 and 2008, one study (paywall) linked signs of narcissistic tendencies—e.g. huge solo shots of the CEO in his company’s annual report—with managerial fraud. Other research suggests the big, bold actions favored by narcissitic CEOs can cause wild swings in performance (pdf) from year to year.

Possible examples:

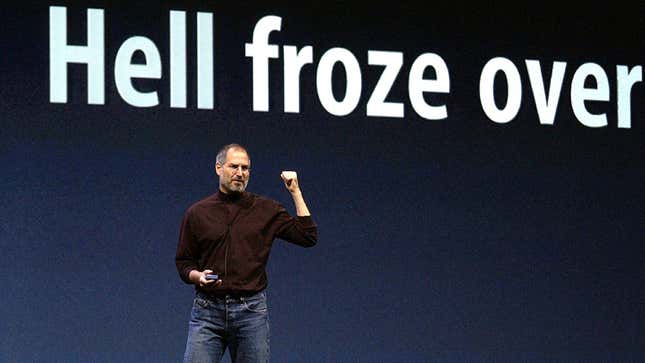

- Steve Jobs. Though Kevin Dutton puts the Apple founder in the psychopath category, UT-EP’s Jones notes that Jobs’ grandiosity and disdain for others, as well as vision and creativity ,tend to be more associated with narcissistic personalities.

- Michael Scott/David Brent. The boss of “The Office” is uproariously narcissistic. As Michael Scott, Steve Carrell’s character in the American version, said, “Would I rather be feared or loved? Easy. Both:

- Silvio Berlusconi. Known for his refusal to relinquish control and his arrogant chauvinism, the former Italian prime minister and media mogul exhibits many narcissistic tendencies, according to Peter K. Jonason (pdf), psychologist at University of Western Sydney.

- Donald Trump. Though the real estate magnate has strong signs of Machiavellian and psychopathic tendencies, they’re overshadowed by the narcissism evident in his political ambitions and reality TV show, The Apprentice, notes Jonason.

Everyday sadism

Motivated by an enjoyment of others’ suffering, sadists display unprovoked aggression and an appetite for cruelty. Note that, of the Dark Tetrad, this category is by far the least explored. The difficulty in devising experiments that appear to inflict suffering without actually doing so meant that it was only in 2013 that Paulhus, Jones, and psychologist Erin Buckels isolated the distinctive traits of everyday sadism (paywall), splintering the Dark Triad into the Dark Tetrad.

Short-term advantages: From the little Dark Tetrad researchers know, it seems that those with everyday sadistic tendencies aren’t as hard-wired to succeed in corporate settings as their more ego-boosting, manipulating Dark Tetrad peers. However, in some office environments, everyday sadists can be good at advancing their own interests by subtly bullying and belittling their coworkers. Their penchant for others’ suffering also makes them shoo-ins for law enforcement and the military. “A sadistic police correctional officer may very well get ahead early because he/she is known as the ‘toughest’ on crime or criminals, and/or earns a reputation of ‘don’t mess with me,'” says Jones.

Long-term problems: Eventually, the co-worker complaints about the cruel gossip, over-the-top pranks, and bullying are likely to overtake any sadistic gains. Other signs of an unchecked person with everyday sadistic traits include police brutality cases, war crimes, sexual harassment suits.

Possible examples:

Characters prone to everyday sadism are harder to enumerate due to the newness of the classification. Though we often call sadistic criminals “psychopaths,” Jones says the latter doesn’t kill for fun, and tends to be motivated by sex, power, money, and immediate gratification. A few obvious (albeit extreme) ones:

- Sailson Jose das Gracas. A 26-year-old Brazilian man who just confessed to having murdered 41 people “for the fun of it.”

- Dexter Morgan. The star of the eponymous Showtime drama enjoys torturing his victims before he kills them. Not exactly “everyday” behavior, but then again, Dexter holds down a job, has meaningful relationships with this family, and (for the most part) only kills other baddies.

- Paul Spector. The serial killer on the TV series The Fall has a wanton, ineffable appetite for inflicting suffering, but feels enough empathy to nurture loving relationship with his young daughter.

Not all bad

Giving power to Dark Tetrad leaders doesn’t always lead to disaster. Machiavellian types can be good leaders in cases where sidestepping morality benefits the company overall, says UT-EP’s Jones. “For example, a president or corporate leader that will do anything to keep jobs, increase productivity, even if it means fudging things, might end up in a good place in the end,” he says. Some research suggests narcissists can thrive in sales positions, especially when their interests are aligned with their company’s. And even psychopathic folks might flourish in jobs that require tremendous calm under pressure, as Kevin Dutton argues—in neurosurgery, for instance.

In truth, all of us have these dark impulses to one degree or another. And despite the empirical evidence of these personality traits’ potential destructiveness, that only holds true for “subclinical” cases, meaning people with elevated Dark Tetrad tendencies are able to function without committing crimes (or, at least, without getting caught). Having a moderate touch of any of the Dark Tetrad qualities isn’t necessarily a bad thing—especially in corporate settings. And though you wouldn’t necessarily want to work with a modern-day Napoleon, many might prefer him to a candidate whose complete lack of narcissism makes him a clingy, insecure drip.

In the mirror, darkly

A glance at the evening’s TV lineup suggests a culture that’s more than comfortable with its dark side. Mad Men‘s Don Draper, the BBC’s Sherlock, Claire and Frank Underwood of House of Cards, The Wolf of Wall Street‘s Jordan Belfort, 24’s Jack Bauer, and The Devil Wears Prada‘s Miranda Priestly are just a few of the Dark Tetradic characters whose morally ambiguous double-whammy of ruthlessness and charisma have thrilled audiences in recent years.

Indeed, admiration for the Dark Tetrad has sufficiently saturated workplace and pop culture enough that a whole discipline has arisen to teach the congenitally nice to toughen up. In the muckier burrows of the internet you’ll find colonies of Dark Triad devotees—men who see emulating narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy as the ticket to “immense personal power“—i.e. career advancement and getting laid. Even in the mainstream, perfectly pleasant people pore over books like The 48 Laws of Power, Get Anyone to Do Anything, Power: Why Some People Have It—and Others Don’t, with all the natural aptitude of a Hufflepuff (the goody-goody house at Hogwarts School in Harry Potter) memorizing the Dark Arts.

But mastering the org-chart equivalent of the Imperius curse is probably not going to help someone low on the Dark Tetrad spectrum suddenly backstab his way to a promotion. The most decisive Dark Tetrad factor—the one characteristic that all four personalities share—can’t be learned: a lack of empathy.

The burdens of empathy

It’s not hard to see how an empty empathy tank would be an advantage in corporate settings. At one extreme, too much empathy can make a person generous to the point of being downright self-destructive—and certainly not someone shareholders would want running a company. But even the middle range of the empathy spectrum can struggle to make tough decisions, like cutting benefits or laying off workers. Protecting the bottom-line is a lot easier if you don’t care about the thousands of employees whose livelihoods depend on your decisions. So despite the research linking the Dark Tetrad with white-collar crime, and the hidden costs to corporations—e.g. lost productivity, missed business opportunities, poorly evaluated risk—it’s small wonder that some psychologists suspect a high concentration of Dark Tetrad traits in corporate boardrooms.

3.5% of executives have psychopathic personalities?

In a study of 200 high-profile executives, 3.5% exhibited psychopathy, according to Robert D. Hare, the leading expert on psychopaths, and Paul Babiak in their 2006 book, Snakes in Suits.

That sounds small—until you consider that incidence is more than three times greater than rates in the general population. UT-EP’s Dan Jones says that based on personal research on the Dark Triad (excluding everyday sadism), he would guess that Machiavellianism is the most common in the general population, followed by narcissism and then psychopathy.

But that’s just the general population. No one knows the rate at which people with Dark Tetradic habits populate our workplaces, however, because it’s unsurprisingly hard to convince companies to let psychologists test their staff for destructive personalities. There’s a reason that nearly all of the Dark Tetrad testing so far has been conducted on college kids and people in prison.

Conducting similar experiments on corporate workers would deepen psychologists’ understanding of the damage the Dark Tetrad might pose, and could also help companies. In his recent taxonomy of dark personalities, that’s what UBC’s Paulhus called for. “Prescreening with one of the [tests] would pay off by preventing inappropriate individuals from being installed in positions where they could cause serious damage,” he wrote.

The tools are out there (those who dare can test themselves with one here). Cynthia Mathieu and her colleagues have found a screening measure designed especially for assessing corporate psychopathy. There are other things companies can do short of instituting full-bore Dark Tetrad testing. For instance, using interview panels, which tend to make it harder for narcissistic or psychopathic personalities to manipulate, making sure to conduct anonymous 360-degree reviews, in which subordinates give feedback on their bosses, or paying attention to signs of interviewees’ empathy and humility.

Everyday sadists are people, too

But limiting the Dark Tetrad’s damage in the workplace will never be simple—neither practically nor morally. Scientists believe that, with the exception of certain cases of Machiavellianism, Dark Tetrad brain chemistry is inborn and can’t be changed.

In the US, employers are barred from discriminating based on mental illness. But might the abundance of empirical evidence on destructive business behaviors provide such justification? We don’t yet know.

Actually, there’s a discomfiting lot about motivation, empathy, and self-control that we don’t know. Research doesn’t capture the rates at which individuals with Dark Tetrad personalities play by society’s rules. People like neuroscientist James Fallon, who accidentally discovered his own psychopathy, might behave in ways that fall outside some social norms, but their personalities don’t necessarily impair their work or harm coworkers. Clearly, some in the Dark Tetrad pantheon have learned to control their nature.

Passing over qualified people on the basis of something they haven’t done—even if they might be prone to doing it—could easily veer into Orwellian “thoughtcrime” territory. (If that sounds fancifully dystopian, consider how in the US criminal justice system, the biased and inexpert application of Robert Hare’s clinical psychopath test currently prevents some felons from being considered for parole.)

Neither is the line between personality quirk and full-blown disability all that clearly defined. Rethink Mental Illness, a UK mental health advocacy group, recently argued that many Dark Tetrad personality traits are easily confused with clinical mental illness—and discrimination against the mentally ill is illegal in certain situations in the UK and many other countries. Encouraging employers to weed out candidates with these qualities has inflamed the stigma against the mentally ill, the group said.

“This is where we get into the legal minefield—is it a psychological disorder?” says UT-EP’s DJones. “If you’re testing for something subclinical, is it fair to say we don’t want you here because you might commit a crime that [you haven’t] done yet?'”

While a company struggling with personnel problems may wish to explore the possibility of testing, he says, any testing ”must be restrained because it can very quickly become a weapon.”

It seems unlikely that companies will start relying on psych evals to ferret out Dark Tetrad folks—particularly if burgeoning research into this subject makes it clearer that their executive suites are crawling with empathy-lacking types. In any case, though, the emerging body of research on the Dark Tetrad in the workplace also suggests a problem more malignant than a test can fix. Destructive though they might be, those of darker disposition also embody the qualities that society reveres as “leadership skills.” It will be hard for paperwork alone to reprogram an entire culture’s belief in what it takes to succeed.

The feature image is by Flickr user Michiel2005 (the image has been cropped); the photo of the statue of Machiavelli is by Flickr user Rafael Robles (the image has been cropped).