PARIS—In the avalanche of commentary that followed the Jan. 7 attack on Charlie Hebdo’s office, an old argument resurfaced, as it does every time a major world event galvanizes social media into action. “I Am Not Charlie Hebdo,” wrote David Brooks in the New York Times. ”Sorry, I am not ‘Charlie’,” wrote Clarence Page in the Chicago Tribune. ”I am not Charlie, I am not brave enough,” wrote Robert Shrimsley in the Financial Times (paywall):

It is an easy thing to proclaim solidarity after their murder and it is heartwarming to see such a collective response. But in the end — like so many other examples of hashtag activism, like #bringbackourgirls campaign over kidnapped Nigerian schoolchildren — it will not make a difference, except to make us feel better.

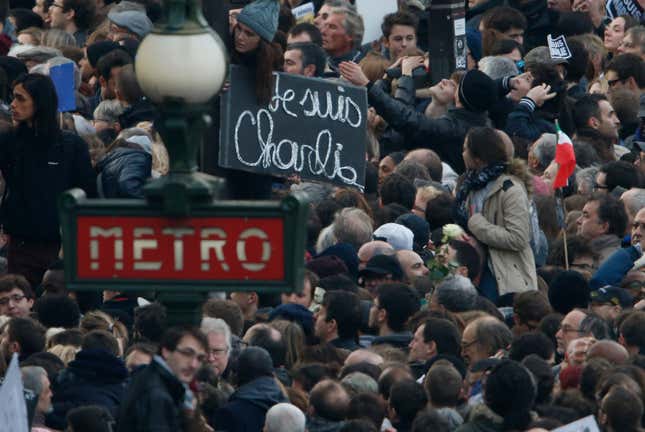

It is not clear who started the #jesuischarlie hashtag, but it migrated quickly from the virtual world into the physical one, from Twitter and the Charlie Hebdo homepage (where it was posted within hours of the massacre) to the billboards and handwritten signs that covered Paris in the ensuing days.

In private homes and in shop windows, “Je suis Charlie” signs were taped across windows. Electronic traffic signs read “nous sommes tous Charlie”—we are all Charlie. At the Hôtel de Ville, Paris’ town hall, two giant banners are draped along the front: “Paris est Charlie,” “Nous sommes Charlie.” On the sides of buildings and on the pavement, graffiti artists spray-painted the words in stencil. You cannot go five minutes in Paris without encountering the slogan.

Not every hashtag will have such influence. Nor should it. But it is 2015. The internet has 3 billion users, including four out of every five Europeans and Americans. Few aspects of our lives are untouched by the internet—and yet we ask if talking to one another online can have any effect.

***

The Jan. 11 “unity march,” as the English-language press dubbed it, or the ”manifestation” in French, didn’t officially start until 3pm, but three hours before the appointed time, Place de la République was filling up. They came up Boulevard du Temple, down Boulevard de Magenta, they came from Boulevard Voltaire, from Rue du Temple, from Rue de Turbigo. Young men clambered up the statue of Marianne. People sang. Somebody tied a black armband on the raised arm of the statue of Liberté.

They raised their papier-mache pencils high, and their cameras higher as they tried to capture the moment. They whipped out phones to take pictures of the crowd, and extended selfie-sticks to take pictures of themselves.

Outside Cafe L’Absinthe, three girls made paper planes from flyers and put them in a box to release later. On the street beyond them marched men and women and children and babies and dogs. Some were white, some brown, some black. Some carried homemade placards, some carried printed sheets of paper, some had simply taken a permanent marker to their t-shirts and chalk to their jackets. All of them proclaimed the same thing: Je suis Charlie.

Silicon Valley utopians are selling us dreams of outlandish autonomous cars and “smart” homes. They are teasing us with windowless planes and 3D-printed food. Newspapers report breathlessly on companies working to “cure death.” We seem to swallow all of these publicity-friendly confections, to accept them as if the future were written and would be here soon enough. Yet we are still debating the role of social networks in steering real-world conversations.

***

By 3pm on the day of the march, you couldn’t move. Place de la République was full. So too were the roads that led to it. Some 1.6 million people crowded the square and the streets around it. That is well over half the entire population of Paris.

People stood around, unsure what to do. So they joined voices, singing the national anthem several times; they applauded, cheering every time a police car or ambulance passed by; and they chanted, “Charlie! Charlie!” “Liberté! Liberté!”

The mood was not sombre, it was not mournful. People came with smiles, with pencils in their hair, with placards on their dogs. More than one man came dressed as Waldo. They came with jokes: “Keep Calm and Charlie On.” They came to celebrate the strength of their beliefs, to say “Je suis Charlie.”

What does that mean? The march in Paris was not necessarily a defiant show of belief that offense should and must be caused. It was not what prognosticators sitting across the channel or across the ocean would have you believe. On Sunday in Paris, “Je suis Charlie” meant that killing 17 people does not diminish the values of the French republic. It would take another 1.6 million lives in Paris and another 2 million in the rest of France for the terrorists to diminish Charlie—to diminish liberté. On Sunday in Paris, the two words came to mean the same thing.