After whimpering through most of 2014, Chinese shadow lending ended the year with a bang. Outstanding “total social financing”—a measure that includes both bank loans and off-balance sheet, or “shadow,” lending—leapt 15.8% in December, up from 15.3% the previous month, reports Bank of America/Merrill Lynch.

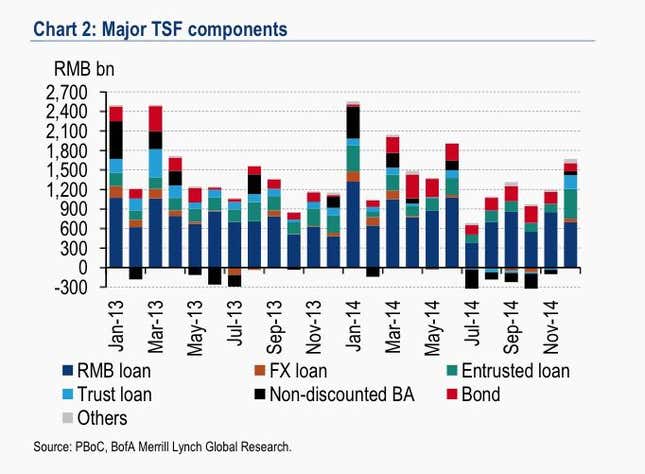

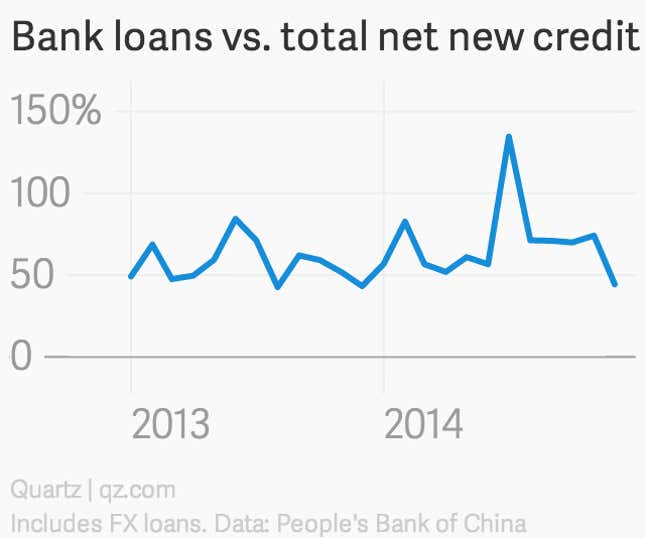

Though outstanding bank loans alone also ticked up in December, compared with the previous month, new bank loans came in lower than analysts expected—meaning shadow banking exploded. The chart below from Bank of America/Merrill Lynch shows a sharp uptick in shadow-banking instruments like trust and entrusted loans. Meanwhile, bank loans as a percentage of total new financing hit 44% in December, the first time since July that it’s fallen below 70%.

So is shadow banking really surging again? Or was December just a fluke?

Firmly in the fluke camp, Julian Evans-Pritchard, economist at Capital Economics, cautions against reading too much into the data. Banks typically cut back on lending late in the year, and the December 2013 cash crunch might be distorting growth rates.

However, BoAML economists Ting Lu, Xiaojia Zhi, and Sylvia Sheng argue the “resurgence of non-bank-loan financing in December might suggest financial regulators eased their grip on shadow banking activities in an effort to support growth.” A marked pickup in a typically short-term shadow-banking instrument called “bankers’ acceptances” suggests that lenders were tiding over cash-desperate firms last month, they added.

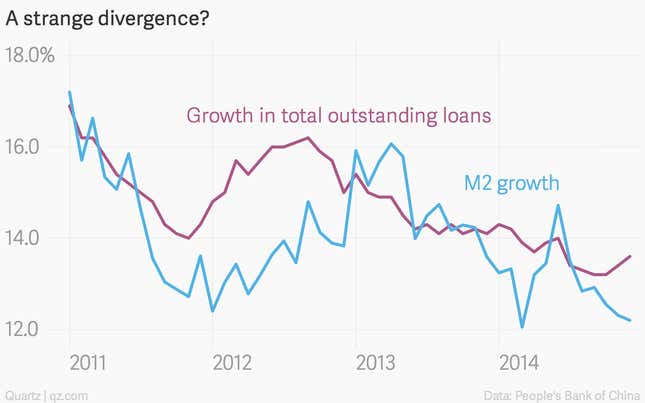

But perhaps the most curious thing of all is the growth in M2, the broadest measure of money supply. (It includes cash actually in circulation, money in checking accounts, longer-term deposits and, more recently, wealth management products). Historically, this indicator of liquidity has been so important that the Chinese government actually sets annual M2 growth targets.

When lenders pump money into the system, M2 should rise as borrowers spend or deposit that money. While bank loan growth and M2 haven’t always run exactly in tandem, a divergence appears to be underway again—and that might well signal that liquidity is drying up:

Any country that grows by forcing consumers to subsidize producers—particularly ones building long-timeline infrastructure projects—depends on steadily rising liquidity to keep its financial system running. China has achieved these cash influxes through its enormous trade surplus and steady investment inflows. But growth in both are now slowing. Despite huge trade surpluses of late, Chinese exporters and companies with access to foreign money have been changing astonishingly little of those dollars, euros or yen into yuan.

That simple drying-up of cash inflows explains some of M2’s ebbing growth. A more recent extenuating factor, says BoAML, might be tighter restrictions on lending between banks. Whatever the cause, the implication is clear. “[T]he PBoC will have to find new ways to inject liquidity in coming months,” writes BoAML. Otherwise, sudden cash crunches likely lie in wait.