Well, 2014, you were a scorcher.

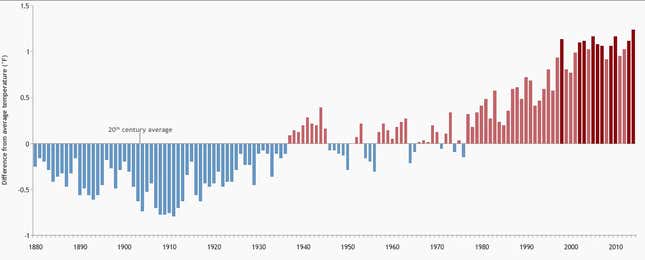

A review of land and ocean temperatures published Jan. 16 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that last year was warmest since records began in 1880. The average temperature was 1.24 degrees higher than the 20th century average.

NASA reported nearly the same reality—a 1.4 degree increase—in a separate, but complementary, analysis. The agency noted that the 10 warmest years in the instrumental record, with the exception of 1998, have all happened within the last decade. And 2014 marked the 38th straight year that global annual temperatures have been above average.

“This was clearly, the warmest year in the ocean records,” said Gavin Schmidt of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in Manhattan. While the average land temperature wasn’t the highest on the record (it was the fourth highest), the warming in the oceans was high enough to, when combined, beat out past records from 2005 and 2010.

Alaska, the western continental United States, the northwest Pacific Ocean, Europe, parts of Siberia and Australia all saw temperature extremes in 2014. For Europe, it was warmest year on record. In Alaska, temperatures were higher than at any time since state records began in 1916.

Some of those temperature extremes could be quantified as economic loss. Aon Benfield, an insurance firms that tracks global disasters, said in a recent report that climate and weather extremes accounted for 72% of global natural disaster losses, totaling over $95 billion, in 2014.

The firm put the cost of the US drought in 2014 at $4 billion. California was particularly hard hit by drought and so far, 2015 has offered the parched state little reprieve. On Jan. 15, NOAA announced on Twitter that over 39% of the state was still under “exceptional” drought and 98% of the state remained under some form of drought this month.

While the effects of high temperatures across land get special focus, much of the extreme warming occurred throughout the world’s oceans. NOAA reported the oceans in 2014 were over a degree warmer than the 20th century average, which broke previous records from 1998 and 2003.

Highlighting the complicated teeter-totter of climate disruption, Arctic sea ice shrank back to the sixth smallest annual extent in 2014, while Antarctic sea ice grew to its largest annual maximum extent.

“The Arctic sea ice is on a very clear downward trend,” Schmidt said. The somewhat counterintuitive sea ice growth in the Antarctic, he said, was due to the complicated regional weather patterns around the continent, which can decouple ice extent from the overall temperature there. “There’s a more complex picture there that doesn’t form neatly in a line,” he said.

But in the rest of the ocean, record warmth was the norm. “Every ocean had parts that were record warmest,” said Thomas R. Karl, director of NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center.

What could packing all of this heat into the oceans do to this year’s weather?

“When you warm up the oceans, they have a much slower response than when you warm up the land,” said Dr. Karl. That ability to retain heat will keep the oceans warm for quite a while. “That gives some added energy for 2015, and the patterns of the ocean temperatures are often very important for helping us to explain the kind of weather we get.”

And what of the connection between temperature and human-induced Greenhouse gas emissions? The jump between yearly records of weather and the longer-term reality of a warming climate can be a hard one to make.

“The attribution of these long term trends is a complicated fingerprinting exercise,” said Dr. Schmidt of the Goddard Institute.

That means you have to factor in everything—ocean, atmosphere, climate confounders like volcanic eruptions, and the human contribution through emissions—and then figure out how they all combine to create the reality we experience on Earth. When you do all of that, according to Schmidt, the biggest fingerprint is a human one.

You can follow Jeff on Twitter at @Jeffdelviscio.