Two days before 1 million bank employees in India were to go on their longest strike in five decades, the Narendra Modi government saved face by agreeing to work on an amicable solution by February—thus persuading them to call it off.

The strike called by the employees of public sector banks, which account for 75% of India’s bank operations, was to be held from Jan. 21 to Jan. 24.

“The six-day shutdown of the banking sector was the longest we had planned since 1966. We planned it in such a way that the four-day strike coincided with a Sunday and a public holiday,” AK Ramesh Babu, president of the Bank Employees Federation of India, told Quartz. While Jan. 25 is a Sunday, India’s Republic Day falls on Jan. 26, which is a national holiday.

The workers, who are demanding better pay and working conditions, have been negotiating with the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), a body comprising the top management representatives of banks. On Jan. 19, after two days of negotiations, the IBA agreed to amicably settle the matter by the first week of February.

“The government clearly felt the need to dissuade us from doing this,” Babu said.

A persistent problem

“If there is no satisfactory outcome, fresh dates for a four or five-day strike in February would be announced,” MV Murali, a convener for the United Forum of Bank Unions, said. The public sector bank employees have also threatened an indefinite strike from Mar. 16 if a deal is not signed.

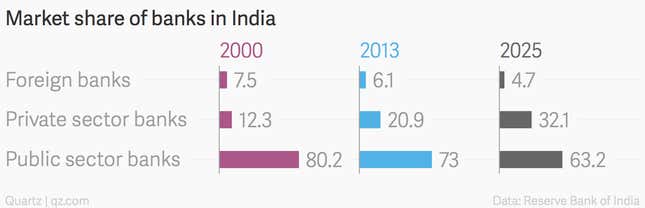

Public sector banks account for 77% of the total deposits in India, and in Mar. 2014, their total capital stood at Rs5,65,200 crore ($91.5 billion). While they command 72% of India’s banking market share, they often face government interference in their operations.

Public sector bank employees, in the officer and clerical posts, want a 19.5% hike in their salaries, but their pay masters, the IBA, is only willing to give them a 12.5% increase.

“In the ’80s, joining a bank in India was similar to a Class-I employee of the central government. Today, we have one of the largest banking systems in the world, yet we are extremely underpaid and made to work over time,” Babu told Quartz.

Long march to revised salary

Bank employees have been demanding a wage hike since October 2012 when their previous pay contracts expired. Since then, they have held frequent one or two-day strikes.

In January this year, the unions brought down their wage hike demand from 40% to 19.5% following negotiations between the bank employees and the IBA. In 2010, the IBA had revised wages by 17.5% for the 2007-2012 period.

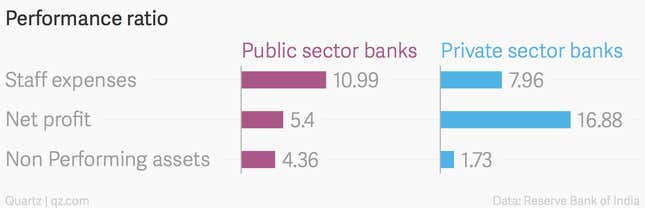

“Their demands are genuine. There is a massive disparity in the pay scale in public sector banks as compared to private sector ones which clearly affects their efficiency and productivity,” said Abizer Diwanji, national leader for financial services at the consulting firm Ernst & Young.

“We are willing to stretch it to a maximum of 19.5%. If we could come down from 40% to 19.5%, the management can increase it from 10% (the IBA’s initial offer),” said another union leader, who did not want to be identified.

With operations at public sector banks being regularly disrupted, private sector banks in India have been steadily increasing their market share in recent times. Also, according to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), 4.36% of assets held by public banks are non-performing, while the same was at 1.73% for private sector banks, signaling an urgent need for overhauling the system.

“Public sector banks have lower profitability and productivity ratios than their private sector competitors. They have lost significant market share, and their asset quality is much weaker—in some cases worsening to grave proportions,” the RBI had said in May 2014.

While promising minimal political interference, the Modi government has said that it intends to reform India’s public sector banks. Perhaps it should begin by listening to the people who help run them.