The search engines of the future will be able to see and hear like humans

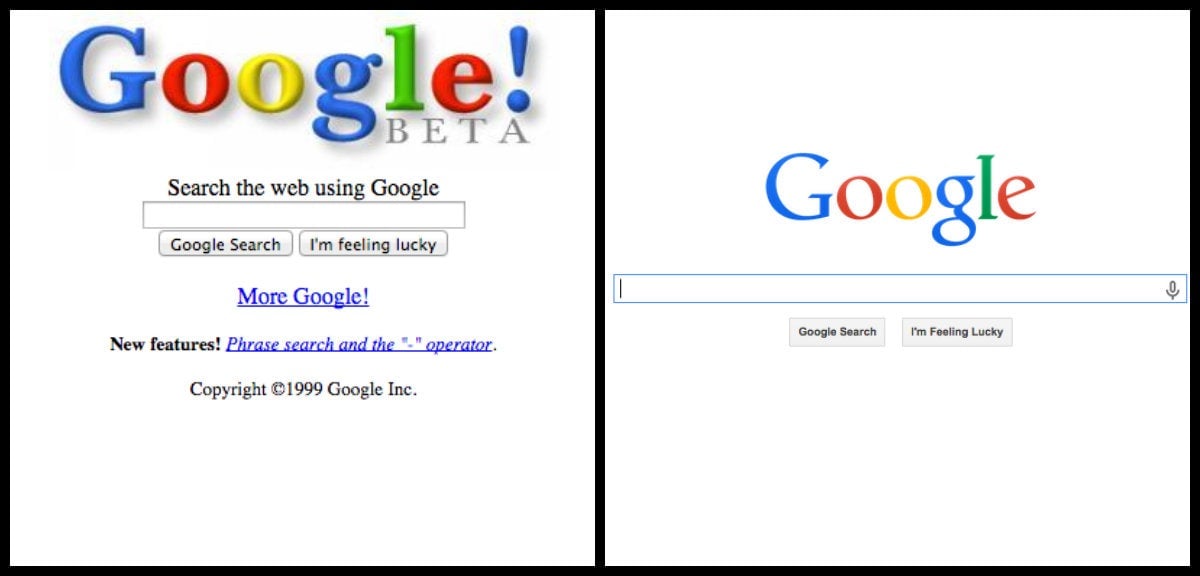

Ever since Google burst onto the scene with its pristine white homepage and barebones results page, search has remained essentially the same. There have been improvements: instant search, location- and history-based results, images, news clippings, video. But any query still begins with a user typing in a set of keywords into a text field and hoping that it serves up the appropriate answer. It is little surprise then that fully one quarter of search results fail, writes Stefan Weitz in his new book, Search: How the Data Explosion Makes us Smarter.

Ever since Google burst onto the scene with its pristine white homepage and barebones results page, search has remained essentially the same. There have been improvements: instant search, location- and history-based results, images, news clippings, video. But any query still begins with a user typing in a set of keywords into a text field and hoping that it serves up the appropriate answer. It is little surprise then that fully one quarter of search results fail, writes Stefan Weitz in his new book, Search: How the Data Explosion Makes us Smarter.

Weitz should know. Since 2009, he has served as a senior director of search at Bing, Microsoft’s Google competitor. (He recently moved to Azure, Microsoft’s cloud computing platform.) During his time in that job, Weitz’s job involved figuring out what was coming in search, what new models exist, and travelling the world to meet people and bring back to Redmond ideas about where search is going. His book is a distillation of his five years of thinking about search.

Too much information

That the internet has overloaded our senses is a common refrain. We now have more information than we can make sense of.

But web users have faced the problem of too much information since the early days of the mainstream internet. “As the growth of the Internet continues at an unprecedented rate—recent industry figures estimate that 1.5 million pages are added to the Internet each day—the average search returns an overwhelming number of results for users to sort through,” Google noted in a press release announcing its official launch in September 1999.

Google solved that problem with a fantastic search engine. But search as envisioned in the 1990s is no longer fit for purpose. The challenge of providing users with the appropriate answers to queries has grown much harder. There are two main reasons for this.

First, there is simply much more internet to sift through. In 1996, the web consisted of some 100,000 sites, totalling an estimated 441 million pages. Today, search engines routinely index more than 10 trillion pages. And that’s just web pages. Previously unrecorded activities like exercising, adjusting the thermostat, commuting, turning lights on and off, or watching television can all generate data now. And data creates data: Give any half decent data scientist two bits of information and she should be able to come up with a new insight.

The second reason is all these data are not available in one, public, indexable space like the web. Social networks keep their data closed off to all but themselves. Internet-connected devices laden with sensors have no means of talking to each other. Even a smartphone very likely has no idea what its owner was doing on his desktop computer.

A “hinge” between man and machine

What does a 21st-century search system look like? Weitz sees it something that is proactive rather than reactive.”Formerly, a stimulus was a query you entered into a search box,” writes Weitz. “In systems like Google Now and Microsoft’s Cortana, the stimulus is no longer a keyword but rather a change in state.” (Emphasis in the original.)

The selling point of products like Google Now and Cortana is that they can provide answers before their users have had a chance to ask the question. About to finish work and head home? Google Now tells you your usual metro line is running with severe delays so maybe you should try another route. About to pop out for lunch? Cortana helpfully suggests carrying an umbrella as rain is forecast. Such utopian ideas of an optimised modern existence aided by technology lie at the heart of much tech research today.

But it’s not just mundane chores. What if you stopped reading an article halfway on your computer but were able to pick up where you left off on your tablet? What if you machine knew you were interested in stories about, for example, Ukraine and that you already had plenty of background on the conflict there. Could it strip out all the things you already know from the latest piece you’re reading? Or add in context that it knows you don’t have?

Weitz sees a more evolved version of this as the future of search. Just as Google became a convenient bridge between existing input technology (text entry using keyboards), the future of search will be a “hinge” that connects the physical and virtual worlds. To get there, technology firms are racing to build analogues to human senses: machine vision, machine hearing, rationale. It is search, Jim, but not as we know it.

Weitz writes:

We must think of search as the omniscient watcher in the sky, aware of everything that is happening on the ground below. For this to happen, search itself needs to be deconstructed into its component tasks: indexing and understanding the world and everything in it; reading senses, so search systems can see and hear (and eventually smell and touch!) and interact with us in more natural ways; and communicating with us humans in contextually appropriate ways, whether that’s in text, in speech, or simply by talking to other machines on our behalf to make things happen in the real world.

Sharing is caring, right?

Such ideas sound far-fetched, even alarming. But the manner in which the largest tech companies gobble up every last bit of data they can get their hands on suggests that Weitz is far from the only one thinking such thoughts.

For search to become “omniscient,” it requires data. Lots and lots of data. That’s why Google, in 2012, combined all of its privacy policies into one—so that it could also combine disparate data troves into one giant pot. But even mighty Google is restricted to data coming from its own websites and services it provides to third parties. It cannot access data on Facebook—Google doesn’t know what you “liked”—or Amazon or within iOS apps. For search to become truly useful in the way that Weitz and his peers in the industry foresee, all these data sources need to cooperate. That’s not going to happen; Google’s data is its competitive advantage. The same applies to its competitors.

“The islands of information are a huge challenge,” Weitz tells Quartz. “If you think about the forces that hold a lot of this back, that notion of data sharing across stores, no one’s figured it out.” Companies are not going to share customer profiles. Nor do users want them to. Tech industry commentators complain about “silos” and “closed ecosystems” created by the reluctance of, for example, Apple to share information with Google. But these silos are what protect users from having their data widely shared.

Rethinking the way the web works

Perhaps it is possible to have data privacy as well as what Weitz calls “a more capable web.” A future in which, to use Weitz’s example, you implicitly “like” something when your pupils dilate and your smart glasses note that or where your phone’s microphones are always on, helping companies record noise levels to figure out whether a venue is empty or full—and we’re ok with that.

This have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too future will not happen without a thorough rethinking of how the web works. Business models need to change. Users’ ownership and delegation of data-use rights needs to change. New models and frameworks will need to be created to make all of this work—and that’s without even going into the technological difficulties of making such a future possible.

One idea is to create “attention banks,” where watching ads earns users services in return. (A small-scale version of this exists: Companies like Jana offer mobile phone users in the poor world free airtime in exchange for viewing ads.) Another idea could be to adopt the Hollywood rights model for data use: People can license a company to use their data for a particular purpose for a limited period of time. When the rights expire, the company must delete that data as well as any secondary data created from it. The travails of the title song from The Wonder Years points to how this works. A still more radical idea: People could start paying for the services they use.