Will Robinhood ever hit the mark, profit-wise?

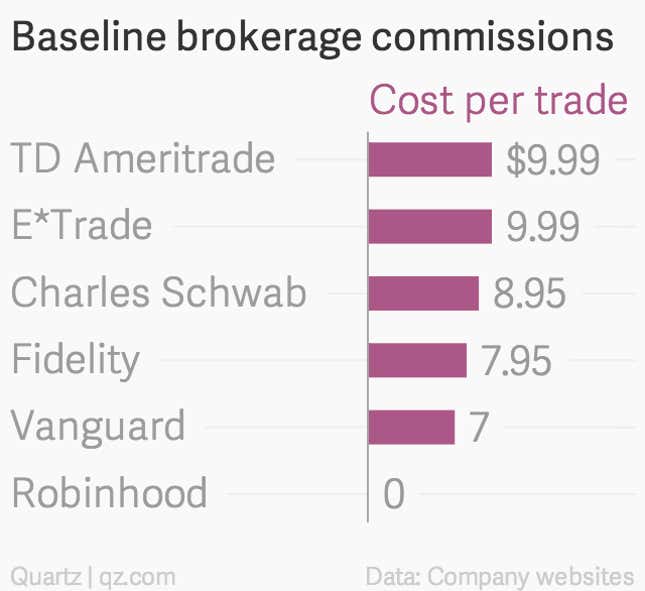

The trading app where people get to buy and sell US stocks for free—unlike with most brokerages, which charge a few dollars per trade—has sent a shot whistling across the bow of the US brokerage industry. The company has sent out more than 300,000 invitations to wait-listed users, many of whom found out about the app through sites like Reddit and Hacker News. (After all, who doesn’t like free?) That’s a big number for such a young firm, though the company declined to disclose how many of those people are actively trading.

The founders, Vladimir Tenev and Baiju Bhatt, say the app was inspired by the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement. They were both working at another startup, building software for big financial firms, when the protests broke out, and Bhatt remembers a friend asking, “Why are you guys doing what you’re doing? You’re part of the problem.”

Venture funding from the likes of Google Ventures, Andreessen Horowitz, and Snoop Dogg means Robinhood can focus on pleasing the masses for now. “Generating a ton of revenue won’t be our focus in the short term,” Bhatt told Quartz.

But industry observers say the startup faces long odds in its effort to more permanently up-end the well-entrenched brokerage model. And they’ll need revenue for Robinhood’s free stock-trading model to last. “Certainly these guys aren’t benevolent,” said Robert Battalio, a Notre Dame finance professor who has studied the operations of brokerage models. “They’re making their money somehow.” But how?

The trouble with young people’s money

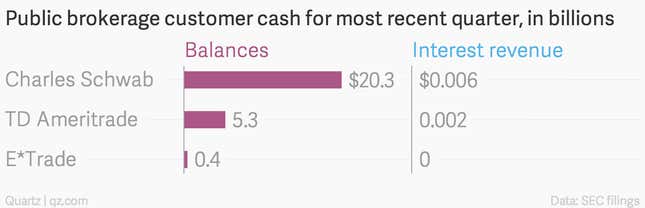

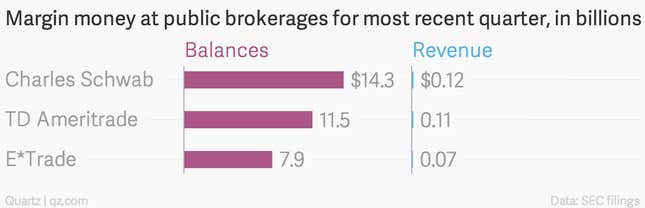

Bhatt and Tenev told Quartz the main ways they’ll make money are investing dormant cash (money that customers have placed in their Robinhood accounts but not put into a stock); margin loans (lending clients money to trade); and licensing the company’s software to news and financial-data websites. It won’t be easy.

For example, a long period of low global interest rates has made it hard to make money on dormant customer cash and margin loans, as numbers from some of the big brokerages show:

Such a strategy also depends, in part, on having a relatively large pool of customer cash to draw on. But Robinhood’s self-described core customer—young investors who are put off by Wall Street but still want to try stock trading—don’t have a lot spare funds lying around.

“Younger users aren’t wealthy yet,” says Richard Repetto, a brokerage analyst for Sandler O’Neill. “They’re a good feeder source, but they don’t have a lot of assets, frankly. They don’t have cash balances and they don’t do big margin loans.”

Zecco was another brokerage startup that tried the zero-commission model. Founded in 2006, it lasted three years before low interest rates compelled it to start charging for trades. It was acquired by the brokerage TradeKing—where trades start at $5—in 2012, the same year Robinhood got its start.

“They were thinking of the same things that Robinhood is thinking about,” Rich Hagen, TradeKing’s CEO, told Quartz. He admires Robinhood’s technology (“They’ve built a really sexy trading application,” he says), but isn’t sure its model can live on interest alone. He also echoed Repetto’s concerns that the target customers might prove unprofitable: Of the 500,000-plus accounts at TradeKing, he said 48% are run by 18 to 35-year-olds, and only 1.4% of those trade on margin.

But Robinhood’s founders say they’re going to try to play the long game. “There’s going to be a land grab for these types of customers,” says Tenev. “Our number one focus for the near term is just getting as many customers as we can.”

The other source of revenue

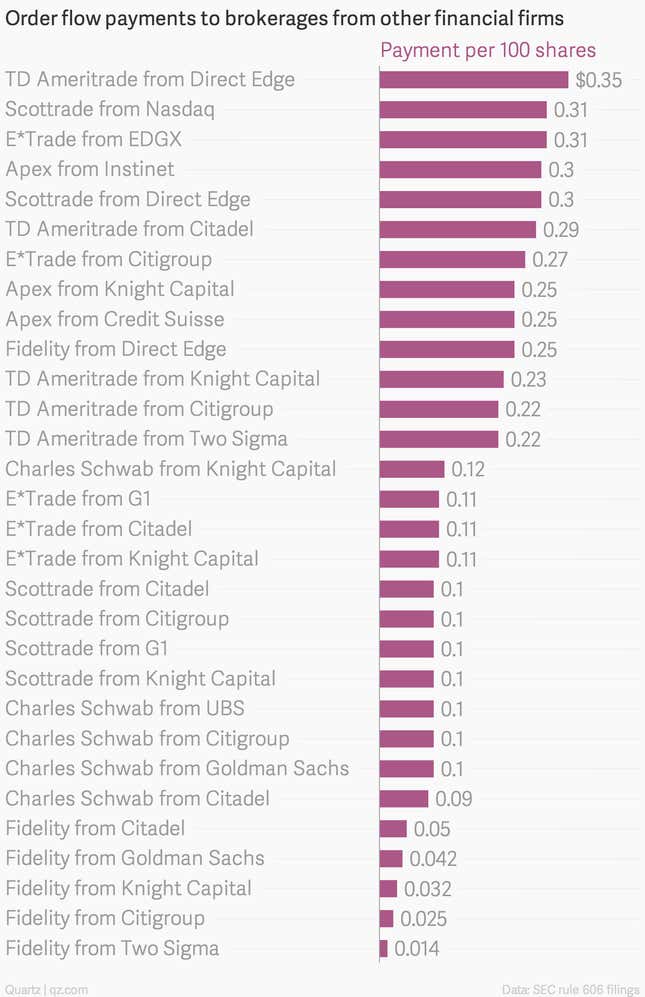

Robinhood also makes at least some money from something known as ”payment for order flow.”A somewhat arcane corner of the brokerage world, this is when hedge funds and other financial firms pay retail brokerages to let them execute orders from the brokerages’ customers. TD Ameritrade has said that it made $77 million from such payments, or more than 9% of its overall revenue, in the last quarter of 2014. E*Trade, another large retail broker, made 5% of its revenue from them in the third quarter. (It hasn’t yet provided that figure for the fourth quarter.)

Brokerages have to file a quarterly document detailing their arrangements with the firms that execute their customers’ orders. In Robinhood’s case that doesn’t reveal how much money it makes from payments for order flow, because it outsources the job to Apex, which clears trades for several brokerages. What Apex makes on such payments, though, is relatively high for the industry:

Robinhood’s founders said that order flow is a “small” part of their business model, but didn’t specify how small. And though it’s a widespread practice, it does show that—at least in some ways—the startup isn’t all that different from its would-be peers.

Time will tell if Robinhood can stick around without charging commissions on trades. “I think they have some time and some money to figure it out,” said Hagen, the TradeKing CEO, “and maybe they do.”