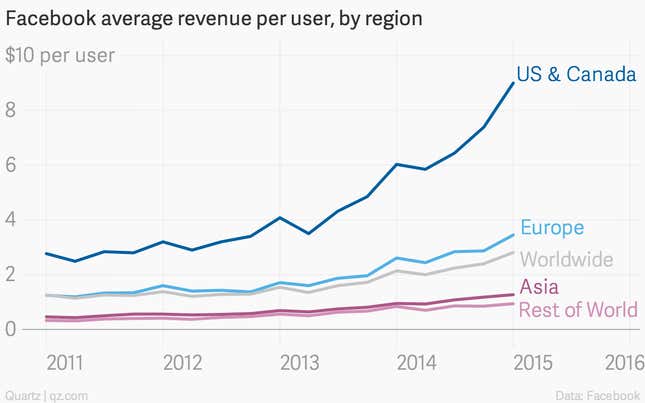

Every American and Canadian Facebook user contributed $9 to the company’s revenue in the fourth quarter last year, up from $6.03 the previous year. That’s a jump of 49% year on year, even though its user base in the region grew by just 3.5%. By contrast, users in Asia-Pacific jumped by 22% but revenue per user grew a more modest 33%—from 95 cents per user at the end of 2013 to $1.27 a year later.

What accounts for Facebook’s supercharged revenue growth in its most mature market? Considering the much lower revenue base in Asia-Pacific, shouldn’t it be easier for Facebook to apply what it’s learned in its home market to boost sales in the rest of the world?

Alas, no. The secret to Facebook’s big boost in North America comes down to something that sounds supremely unsexy, but is also at the core of Facebook’s efforts: measurement and attribution. In other words, data.

“Over the past year and half the investments we’ve made in building out that measurement have paid off,” Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s operations head, said in an earnings call yesterday. ”We’ve been able to ad test, Facebook ads versus no Facebook ads and what the effectiveness is on their sales.”

That Facebook uses data about its billion-plus users to more effectively target ads is by now as well known as the social network’s “like” button. But that data has another, equally important use: tracking the effectiveness of those ads. For well over a year, Facebook has invested heavily in products and analysis to better understand what happens after it serves an ad. As a result, the number of ads served in the fourth quarter is down 65%. But the average price per ad is up a whopping 335%, according to the company’s finance chief.

That’s great for Facebook. But here’s the problem: Measurement relies on data, lots of it. To accurately measure the effectiveness of an ad, Facebook needs to track users across multiple devices, on websites outside its own social network, and out in the real world. It does this through by putting its trackers on sites around the web and by using third-party data, such as from supermarket loyalty cards and data brokers. (Quartz has previously explained how this measurement works in great detail.)

Rich sources of such data are readily available in North America and, to a lesser extent, in Europe. But they are virtually non-existent in the developing world. As a result, Facebook is increasingly a two-speed business.