The US victory lap on job creation is in full swing, with just 5.8% of American workers who want jobs unable to find one.

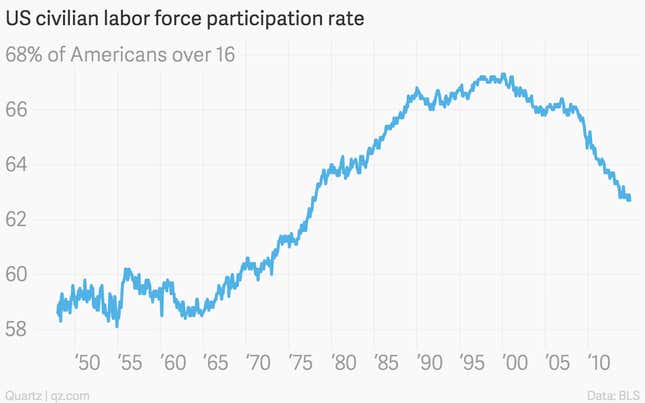

But as that number falls, there is looming specter behind it: The number of Americans who want to work—who are participating in the labor force—has been on a steady downward plunge to levels not seen since the seventies.

This is a significant change in the economy, but it’s not entirely clear yet why it’s happening—while the large Baby Boom generation is retiring, demographers say that isn’t the reason we’re seeing a reduction in the labor force participation rate. That suggests the culprit is other social and cultural trends, and that maybe the shrinking participation rate actually isn’t a bad thing.

“What is our socially desirable rate of participation?” Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau, a Carnegie Mellon economist currently on leave at the San Francisco Federal Reserve bank, asks. ”The truth is, we don’t know. There’s an immediate reaction to think that a decline in participation is necessarily a bad thing, [but] you can imagine it as an improvement of society’s organization of work, and individuals desire not to work, and that is the best outcome.”

Bottom’s up, top’s down

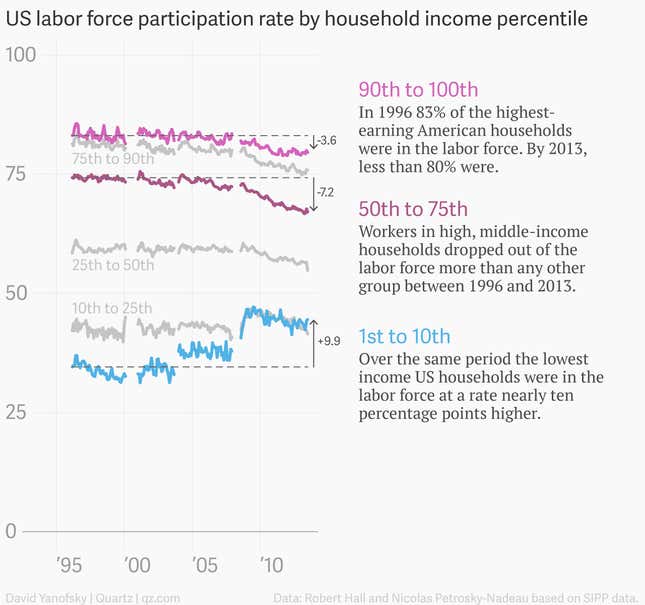

Petrosky-Nadeau and Stanford economist Robert Hall are trying to come up with an answer to this question by figuring out exactly who is leaving the labor force. Using a survey of Americans that asks whether and how much they work, how much they earn and how frequently they use government programs, they are able to break out labor force participation by income, with some interesting results:

When Hall testified about this research before the Senate finance committee last week, his primary conclusion was that the government safety net is not leading the poorest Americans to avoid work: Households making an average of less than $935 a month, or $11,220 a year, between 1996 and 2013, have seen their participation in the labor force rise steadily over the last two decades. The lowest quartile of American earners, earning an average of $1,740 a month, or $20,880 annually, have seen their participation rate rise as well. One probable reason: Declining real wages at the bottom mean that more work must be done in each household to maintain the same standard of living.

Between the bottom quartile and the median income—$3,360 a month or $40,032 annually—the trend starts to diverge. The lower middle-income households have seen a small reduction in labor force participation, but that’s nothing compared to households in the high middle-income quartile, who earn up to $5,920 a month or $71,000 a year. Since 1996, the share of workers in those households has fallen by 7.2 percentage points, the highest of all. As notable: The top 10 percent of American earning households have seen their participation fall 3.6 percentage points.

What it means: The richest Americans don’t have to work as much as they used to, but the poor are working more to maintain their standard of living.

Factory workers and chilled-out teens

Take a look at the way labor force participation has changed between 1998-2000 and 2011-2013:

The first thing you note is that a lot of high-income teens aren’t working. They don’t have to: Their parents are probably prioritizing education over employment. Petrosky-Nadeau says teens make up 40% of the overall drop in labor force participation, and Hall notes that the bulk of the reduction comes from teens and young people in their early twenties.

Because so much of the drop occurs on the high-income side, Hall suggests that a government policy reaction—and particularly attempts to cut the social safety net—isn’t necessary.”A study of the data on the decline does not suggest the desirability of policy changes focusing on reversing the decline,” Hall told the Senate.

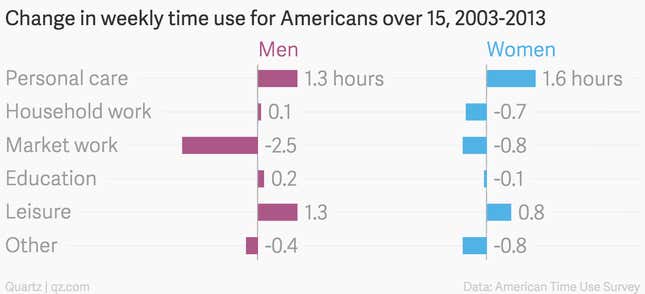

Hall suggests that maybe we are approaching that “improvement of society’s organization of work” Petrosky-Nadeau talked about earlier: Less work, more (screen-oriented) leisure. “Entertainment is a lot cheaper than it was 20 years ago,” Petrosky-Nadeau notes.

Take a look at changes in American time usage:

Unequal organization

But several problems arise from this analysis. One is that there is some non-trivial number of working-age Americans who have left the workforce not because they can spend more time watching TV but because they have trouble finding a job they want: This hollowing-out of middle class jobs, often cited as manufacturing work replaced by trade or automation, that could be behind the plunge in labor force participation for upper middle-income Americans.

The second question is about those chilled-out teens: Are they going to school, or just fooling around? With time spent on education not rising significantly and a dearth of early job experience, there is a fear that those teens may not be ready to work—or have the same earnings opportunities as their parents—when they hit prime age. Petrosky-Nadeau suggests that this may lead policymakers to think more about jobs training and apprenticeship programs.

The final problem is the opposite of the entitlements and social safety net question we’ve been focused on: Should society be worried about low-income people, and particularly low-income people over 60, having to work increasing hours to make ends meet? Shouldn’t everyone get to share in the new economy of leisure?

More to learn

Hall and Petrosky-Nadeau still have more to learn about how people make their decision to join the labor force, and how various combinations of household income and size, access to government programs, age and skill-level lead people to enter or exit the labor force.

But just in their preliminary work, you can see both the promise of the new global economy—the chance that we’ll be able to spend less time working and more time doing other things—as well as its peril—that those opportunities will be restricted to a highly-skilled minority.