Nice one, Finland! This week, the Finnish government sold a highly unusual bond. Buyers lined up to pay for the privilege to lend the country money—the debt was priced at an interest rate of -0.017%. This means that when the debt comes due in a few years, Finns will owe investors less than the face value of the bonds.

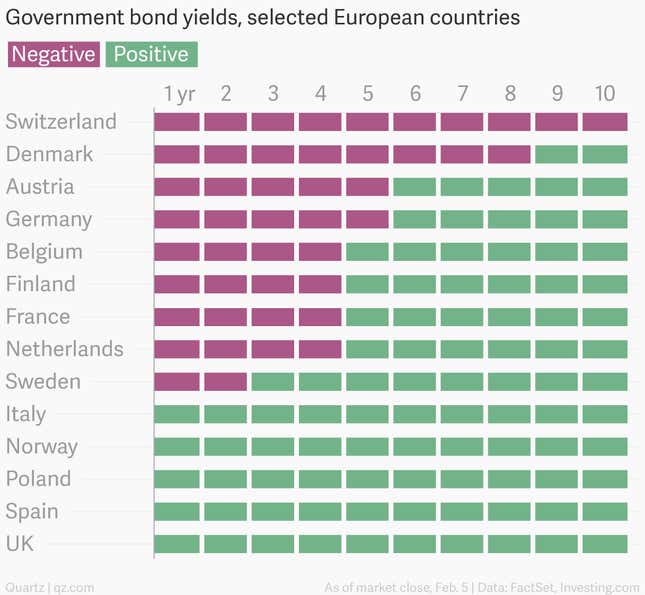

Finland was the first to issue long-dated debt at a negative rate, but in the secondary market an increasing number of bonds are trading at negative rates. More than $1 trillion worth of European government debt now finds itself in this unusual state.

Buying a sure money-loser is weird, to be sure, but these are weird times. Remember that a bond’s price moves inversely to its yield, so the prevalence of negative rates reflects a rising demand for these bonds, a falling supply, or some combination of both.

Most notably, the European Central Bank has pledged to buy some €1 trillion ($1.15 trillion) in euro zone bonds, starting next month. Bond prices have risen (and yields fallen) in anticipation of this big player moving into the market and buying everything in sight. For good measure, the ECB also has cut one of its benchmark interest rates below zero in hopes of stimulating the region’s moribund economy.

While the ECB has been revving up its printing presses, the value of the euro has been falling. For countries that try to keep their currencies in line with the euro, this is a problem. That’s why Switzerland and Denmark’s increasingly desperate attempts to keep their currencies from appreciating too much against the euro—central banks in both countries have pushed benchmark short-term rates deep below zero—are attracting speculators buying bonds in hopes that the franc and krone will rise further.

In general, near- or below-zero interest rates reflect weak, deflationary economies that are not responding to the usual monetary stimulus. But in these cases, investors are clamoring for a safe place to park their cash, even if they know they’ll lose a bit in the process. And that speaks volumes about the dearth of better alternatives.